Bible Leaf

Bible Leaf

French (Paris), 1240

Language: Latin

Single leaf: O.T., Maccabees, IX, 12-X, 22

ink on vellum

height 20 cm

Portland State University Library Special Collections

Mss. 13, Rose-Wright Manuscript Collection no. 15

Chloe Massarello, Medieval Portland Senior Capstone Student, 2008

The Portland State University Special Collections is home to a single leaf from a medieval Bible. It has been dated to the thirteenth century, circa 1240, and originates from Paris, France. Part of the Rose-Wright collection, it is an unimposing and small page without any of the elaborate decoration, one comes to think of when conjuring up popular images of books manufactured during the Middle Ages. After looking over the neat lettering and the quiet but beautiful decoration, it becomes easy to imagine someone sitting down with their Bible to read. The leaf's size and elegant simplicity conjure up a feeling infinitely more personal than that evoked by an elaborate page.

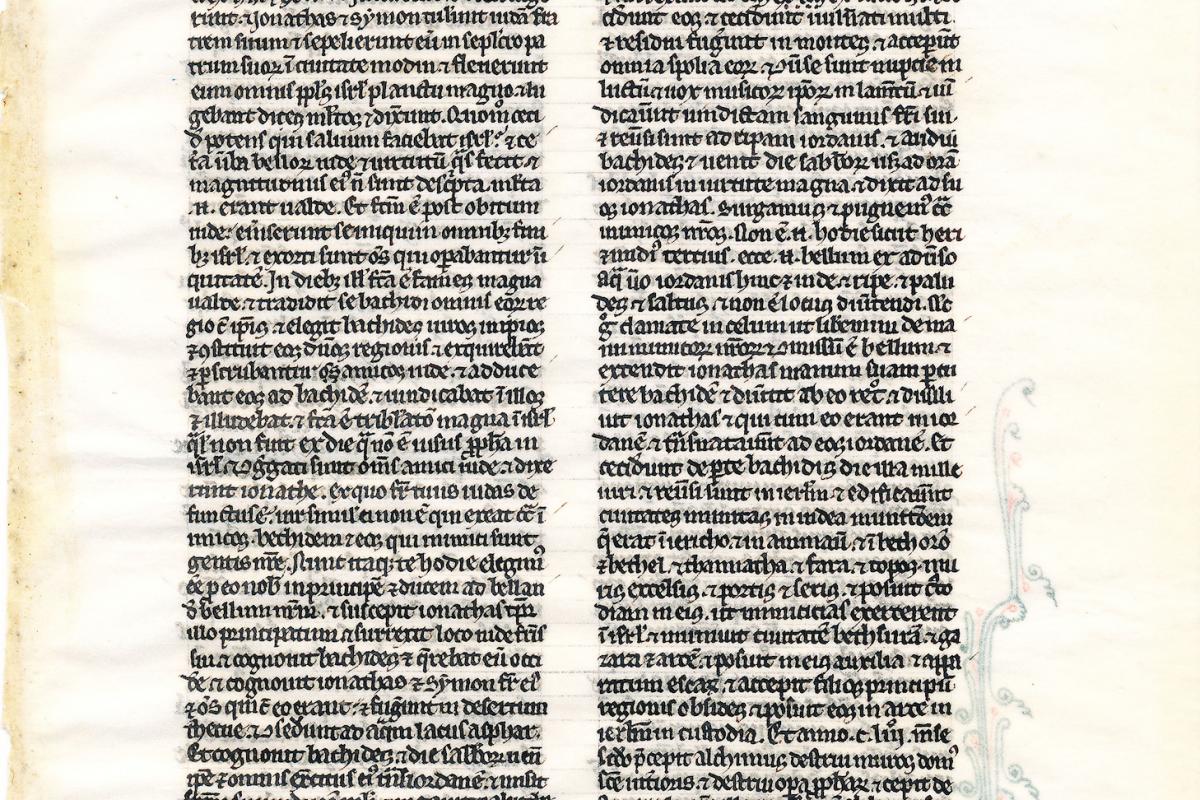

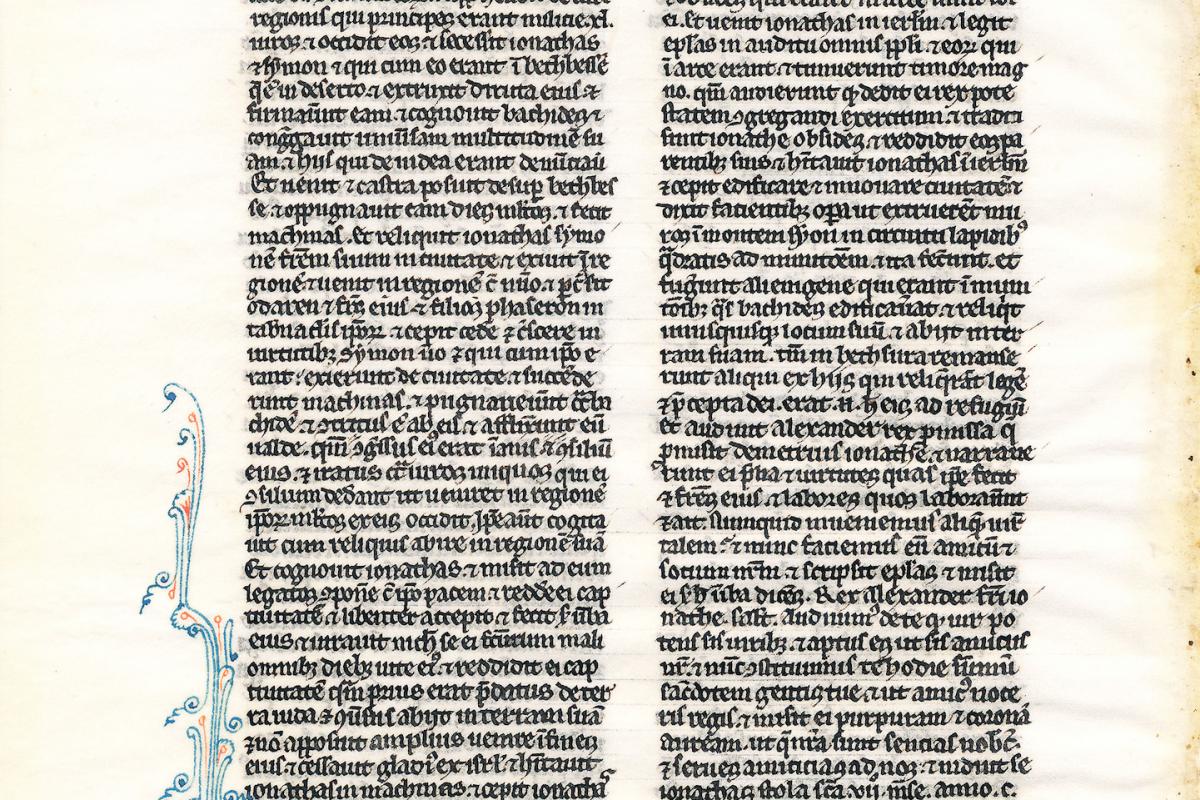

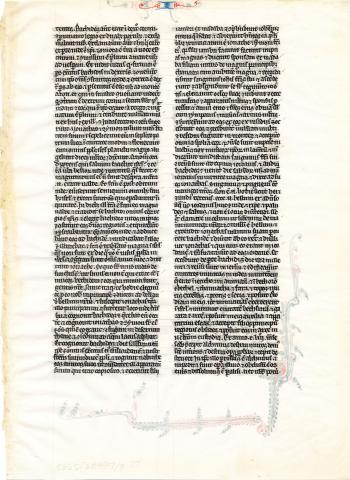

Twenty centimeters long and made of vellum, the page appears exceedingly delicate. The vellum is so thin that it is to a large degree translucent, and when examining one side the writing from the other can be seen as dark shadows. It would have been treated with chalk or something similar in order to whiten the page, and the leaf is remarkably white, despite the passage of time. Around the edges of the leaf is a darker stain where the frame that the leaf rests in has had contact with it. Also, the side of the page that would have originally been bound is a much darker yellow and has a rough edge where it was removed from the binding. Originally, the leaf would have been sewn into a book, and the book would have had wooden covers attached.[1] No identifiable signs of the sewing remain where the page would have been attached, but the margin between the edge and the script is narrower than on the opposite edge, suggesting that the page did not remain quite whole when it was removed. There are a few tiny holes in the vellum scattered throughout the main body of the page, but they are so small that they are almost unnoticeable. Also, hardly discernible are faint striations on the vellum. Patches of these striations exist on the right and left edges, oriented diagonally, while vertical striations exist near the top and bottom. These markings are most apparent on the verso. The recto has many fewer marks and, although it is hard to tell for certain, some of the marks on the recto could simply have transferred to the verso because of the thin and delicate nature of the vellum. Overall, the leaf seems to be in excellent condition.

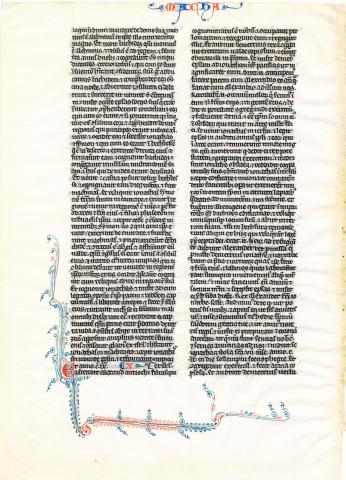

At the top of the recto is the letter "I" in blue ink, flanked on either side by a little flower with three petals in red. In the thirteenth century when the leaf was produced, blue and red were particularly favored colors in manuscript decoration.[2] The text, written in Latin, is divided into two columns narrowly spaced apart that run down the center. Each column has fifty lines in black ink that remain vibrant. No fading is to be found. The ruling used as a guide for the scribe is still visible in faint black ink, marking out each line and the borders of both columns. Little tick marks can be seen next to random lines. The lettering is very small and appears to be in the style known as Gothic textura, which began being used in northern France sometime in the eleventh century.[3] Apart from the letter "I" with its flowers, the recto contains no decoration.

The verso has the exact same general layout as the recto. The two columns running down the center with their ruling providing a guide for the scribe are there unchanged, and the heading at the top of the page is done in the same style as that on the recto. The heading on the verso, however, says "Macha" in capital letters. The letters are done in alternating red and blue ink, with the M in red, the first A in blue, and so forth. The letters are flanked by the same little flowers as the heading on the recto, but the flowers are in blue ink. The lettering of both headings is extremely different from that of the general text and is done in a much more rounded and whimsical style. The same style can be seen in other manuscripts from thirteenth-century Paris, France.[4] Along the left side and the bottom of the page is a floral design drawn in red and blue ink. It is strikingly similar to decorations found in a group of manuscripts dubbed the Morgan 92 group by Robert Branner.[5] It is a simple and somewhat abstract design that compliments the heading and brings to mind creeping vines and climbing flowers. At the bottom corner of the left column, the design incorporates a red letter "E" of roughly three lines in height. The only other letter in the main body of text that is given special attention is the letter "X," only a short space from the "E." The "X" is also done in red ink but does not join into the design because it is in the middle of the second to the last line in the column. It is surrounded by blue decoration that includes a small flower.

In Paris, demand for books was high, especially among the students at the university. Poorer students could rent the books they needed for class, but students from affluent families often commissioned finely decorated books for use in their studies. The University of Paris actually published its own version of the Bible, and it was quite popular among the students.[6] The Bible was a classroom requirement, and around the year 1230 smaller Bibles, called pocket Bibles, began to be produced in order to make the book easier to carry around.[7] It is possible that the leaf came from a student's pocket Bible. Due to the fact that the leaf has been separated from its original context, it is impossible to determine if it was once part of a University Bible, since the order of the books and the presence of particular prologues are what would be needed to make such a determination.[8]

The text itself is a section from Maccabees, which is considered apocrypha now and was controversial even early on. It was thought that Maccabees should be considered uncanonical, but they had influential supporters such as Augustine and Jerome.[9] Throughout the Middle Ages and before, the interpretation of Maccabees changed. In the tenth century, one can find Judas Maccabaeus being used as an example worthy of the warrior leaders of society to imitate, and it is to this role that he returned in later years when secular literature and characters such as King Arthur became role models. Poetry, especially that produced in the thirteenth century in Picardy, northern France, forged the figure of Judas into a proper mirror for princes.[10] Since the Bible leaf came from the same area of France, it is easy to imagine its reader being already familiar with contemporary poetry, and finding in his or her Bible not only spiritual guidance but an image worthy of imitation in secular life.

Notes

[1] Ibid., 22.

[2] Robert Branner, Manuscript Painting in Paris During the Reign of Saint Louis: A Study of Styles (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1977), 1.

[3] Bernhard Bischoff, Latin Paleography: Antiquity and the Middle Ages (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990), 127.

[4] Jacques Dalarun, Le Moyen Age en Lumiere (Paris: Fayard, 2002), 12-15.

[5] Branner, Manuscript Painting in Paris During the Reign of Saint Louis, 58.

[6] Ibid., 2-3.

[7] Ibid., 10.

[8] Ibid., 16.

[9] Jean Dunbabin, "The Maccabees as Exemplars in the Tenth and Eleventh Centuries," in Katherine Walsh and Diana Wood, eds., The Bible in the Medieval World: Essays in Memory of Beryl Smalley (Oxford: Blackwell, 1985), 31.

[10] Ibid., 41.

Bibliography

Bischoff, Bernhard. Latin Paleography: Antiquity and the Middle Ages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990.

Branner, Robert. Manuscript Painting in Paris During the Reign of Saint Louis: A Study of Styles. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1977.

Brown, Michelle P. Understanding Illuminated Manuscripts: A Guide to Technical Terms. Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 1994.

Dalarun, Jacques. Le Moyen Age en Lumiere. Paris: Fayard, 2002.

Dunbabin, Jean. "The Maccabees as Exemplars in the Tenth and Eleventh Centuries." In Katherine Walsh and Diana Wood, eds. The Bible in the Medieval World: Essays in Memory of Beryl Smalley. Vol. 4 of Studies in Church History: Subsidia. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1985.