Book of Hours, Use of Rome

Book of Hours, Use of Rome

French, 3rd quarter 15th century

Language: Latin

height 11 cm

width 8 cm

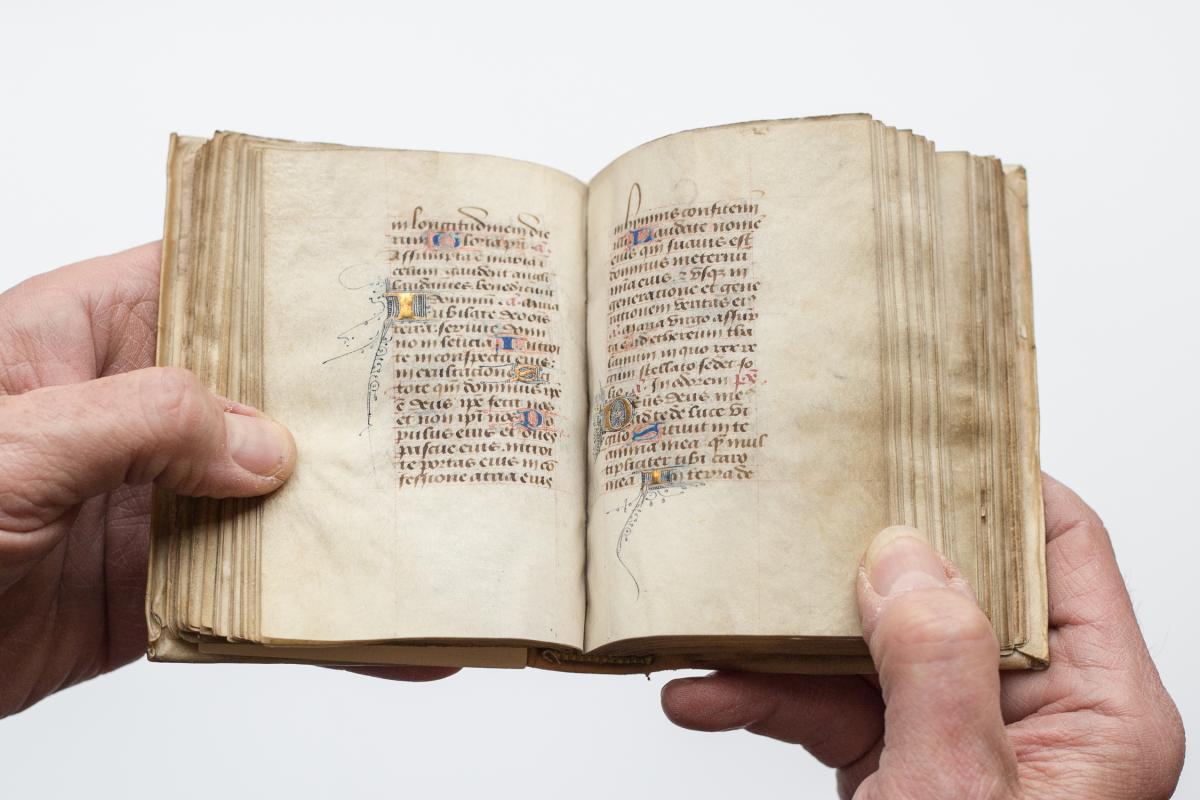

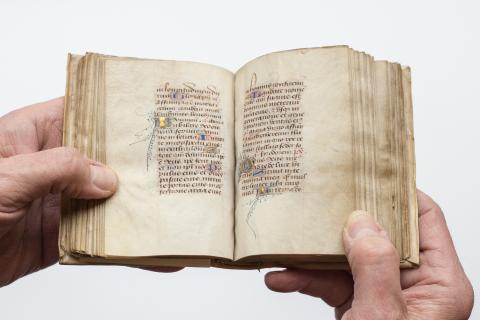

N. France. 121 leaves (11.0 X 8.0 cm). Bâtard script. 18 lines. Gatherings mostly of 8. Text in Latin and French: Calendar, Gospel Lessons, Hours of the Virgin, Psalms, Litany, Hours of the Cross, of the Holy Spirit, Prayers to Saints. 2 large and 8 small miniatures, decorated initials, and borders. Binding: vellum.

Provenance and Prior Publication: John Wilson (ex libris); John S. Doxey (inscription, 1870); Publications: Parshall 10, p. 27 and Seymour De Ricci, with the assistance of W. J. Wilson, Census of Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts

Multnomah County Library No: W091 H811 - 31168045410220

Parshall, Peter. Illuminated Manuscripts from Portland Area Collections. Portland, OR: Portland Art Museum, 1978, p. 27 - Quoted with permission

Here we turn our attention to the prolific centers of illumination in northern France which had largely eclipsed Paris by the second half of the century. The miniatures of this manuscript show close affinities with the bland narrative style of the so-called Maitre Francois. Active in the 1460s and '70s, Maître Francois seems to have worked close to the principal master of the French court, Jean Fouquet. In fact, he has been identified as Fouquet's son, though without conclusive evidence. The border decoration is adapted from patterns common in Bruges and frequently employed in French workshops by this time. The prominence given the Benedictine St. Marcoule (granted a miniature), and the inclusion in the calendar of Vincent of Saragossa {especially venerated in certain Benedictine abbeys in France), suggest the book may have been intended for use by a member of this monastic order. Manuscripts from the François workshop are generally localized in Tours where Fouquet lived and worked most of his life.

Wilma Fitzgerald, PhD, SP - Quoted with permission from an unpublished study

Liber horarum cum kalendario. Saec. XV ex. Cover: 190 x 90 mm., FF. iii + 122 + iii. [without foliation] 108 x 75 (60 x 36) mm., 1 col., 18 lines. Initials red and gold with red and blue filigree. Complete calendar (no vacant lines) in French, entries not Parisian but rather northern France. For a woman. On front fly leaf ii the notice: Horae beatae Mariae Virginis cum calendrio. This 12 mo manuscript on vellum of the fifteenth century (14) is ornamented with elegant borders of birds, fruits, flowers etc. and numerous capitals and contains also 10 very pretty miniatures illuminated in gold and colours. It is written on 96 leaves. John S. Darcy June 6th 1870. Cover is of vellum on paste boards. The manuscript was purchased by John Wilson 13 February 1890 from Henry Young dealer. Wilson's Bookplate on end board with catalogue sales slip # 25.

Note: [ff. 1-12] Calendar. Hours B.M.V, Holy Cross, Holy spirit. Prayer [f. 120] to St. Marculsus (Marculfo, Marcou, Marcoul abbot of Nanteuil honored at Rheims. He is invoked as pater familias and is possibly here as a family patron. Feast day May 1. Not included in calendar. See Biblioteca Sanctorum Vol. 8, 748-751 and BHL 5266).

Nicole Aue, Medieval Portland Capstone Student, Summer 2005

This paper will offer an account of the origin and possible patronage of the Horae Beatae Maria Virgines, a French Book of Hours that is housed in the Multnomah County Public Library in Portland, Oregon. The rare book collector John Wilson donated the book to the library in the 19th century, but where he acquired it is unknown. Although it is apparent by the style and by the particular saints and scenes included in the book that it dates to the 15th century, it is in excellent condition, completely intact but appears to have been rebound at some point since its creation. Of particular note is the reverence given to natural themes in the book, and to hermit saints, four of whom appear in their own illuminated miniatures.

Judging by the red highlighting of St. Genevieve, Paris' patron saint, in the calendar section for January 3, the manuscript was likely created in Paris (DeHamel, 184). Applying Christopher DeHamel's basic method of identifying the Use of a Book of Hours, I would guess that the book was intended for the Use of Rome. DeHamel's method entails locating the antiphons and the capitula in both the Prime and the None in the Hours of the Virgin and matching them to those already established as belonging to the Use of a specific location (180).

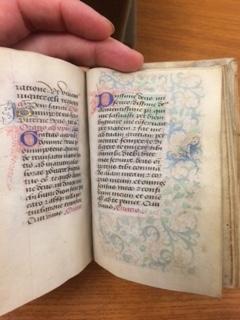

The book is only about 3" x 5" in size, which was fashionable for the time period, as Books of Hours were often carried on the belt and shown off as a status symbol (Harthan, 34). The various prayers and sections in the book include a calendar, gospel lessons, Hours of the Virgin, Psalms, Litany, Hours of the Cross, Hours of the Holy Spirit, and prayers to various saints. (Parshall, 27) Ten miniatures--two large and eight small--accompany some of the hours and prayers. There are also hundreds of decorative initials in blue and red with plenty of ornamental flourishing, very similar to that which can be found in the Parisian St. Denis Missal from 1350, now housed in the Victoria and Albert Museum (Watson, 31). Several gorgeous historiated initials with a thoroughly three-dimensional form that are filled with blue flowers against a pool of gold appear near the middle of the book in the Hours of the Virgin. The manuscript is made with vellum paper, and the principal ink colors used are bright reds, greens, blues, and golds. In general, there is not much unusual about the appearance of the book. It seems to be a fairly generic 15th-century Book of Hours from northern France, albeit a quite beautiful one.

The illustrations have picked up a few realisms from the Italian Renaissance, such as attempted foreshortening and perspective, and a somewhat realistic architectural setting for the Annunciation scene. But overall, the renderings are mostly dominated by flat line-art with thin gold lines used as a highlighting effect. Bodies are subtly outlined in dark ink, which is most obviously visible in the Crucifixion scene and in the Man of Sorrows. In this regard, the miniatures are similar to those from the French Playfair Hours of 1480, now located in the Bibliotheque Nationale de France, but are less crude and more detailed (Watson, 67).

St. John the Evangelist

The very first miniature to appear is St. John on the Island of Patmos, which is a very common theme in books of hours, possibly because St. John was the patron saint of booksellers, writers, and artists (Giorgi, 197). St. John is pictured on the island with his symbol, the eagle, writing the Book of Revelations. He seems content to be writing at the water’s edge under a blue sky with mountains behind him. The border illumination around the St. John miniature exhibits very detailed and ornate foliate designs. The fruit and flowers chosen to supplement the St. John miniature include strawberries and violets, common symbols in manuscript embellishment that represent righteousness and humility, respectively (Post, 65).

The Annunciation

In the Hours of the Virgin section appears the second miniature, a full-size Annunciation scene. The artist used the miniature’s frame as a means to create an architectural setting. The frame’s edges are pillars and the top of the frame is an archway into the space that houses the Virgin. The tiles of the green floor recede in an imperfectly rendered perspective, yet the sense of three-dimensional space is effective nonetheless. The effect of having the right rear corner recede into open outdoor air enhances the realism. Gabriel, in red, sneaks up behind Mary, who wears her characteristic imperial blue. Mary kneels humbly. The intricate highlighting of form created with delicate lines of gold ink is especially beautiful in this scene. Unfortunately, the paint has been smeared on the left side where Mary is kneeling, making her features rather blurry. The border illumination around the Annunciation includes carnations, a symbol of Christ’s incarnation, and a rooster, associated with the dawn of a new day (Carr-Gomm, 239).

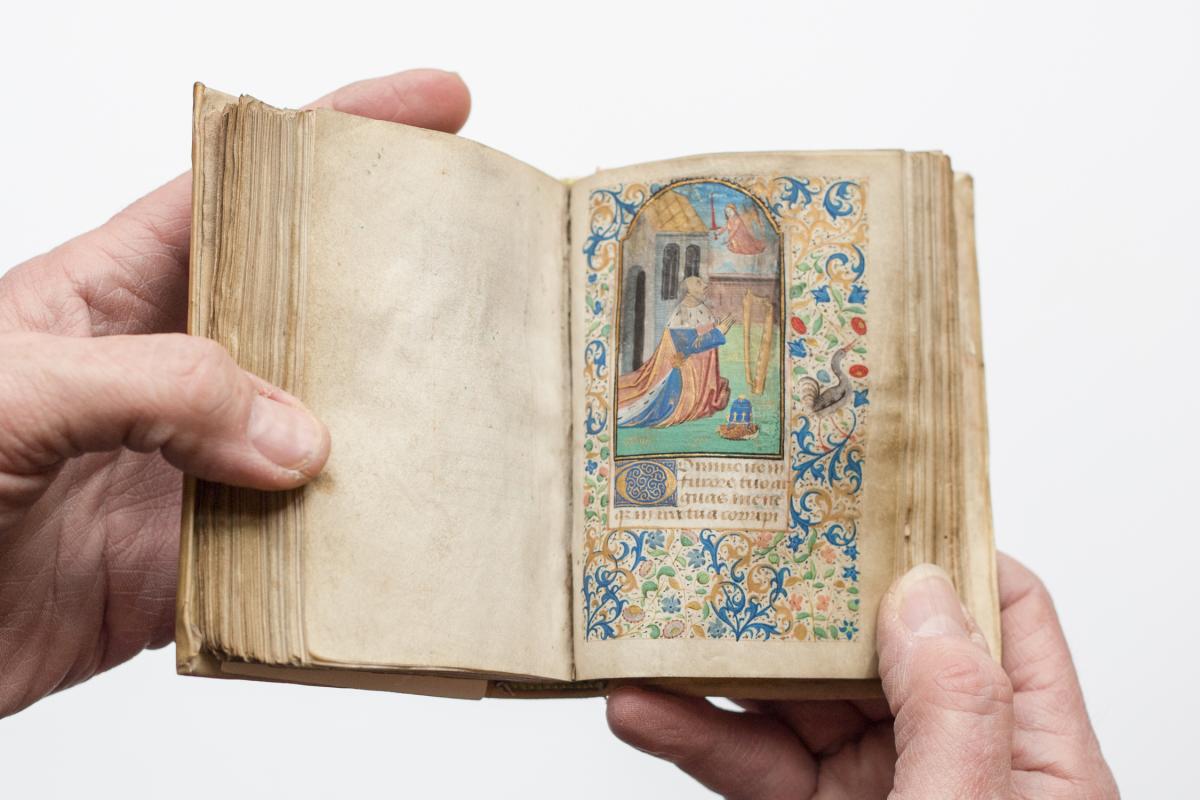

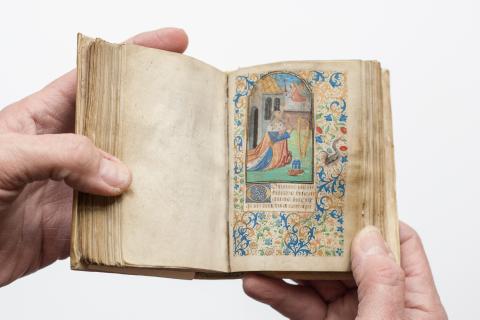

King David

The third, and the only other full-sized miniature, depicts King David praying in the setting of a castle courtyard. David repenting is the standard theme chosen to head the Psalms section of a Book of Hours, and so is appropriately placed here (Male, 75). Unlike the other individuals portrayed in the book, David is depicted in what looks like contemporary 15th-century French royal garb. Perhaps this pays homage to the King of France, thought by the medieval French to be "the most Christian king," and endowed with divine earthly rulership by God himself (Beaune, 19). Prayers for the French king could buy between 10 and 100 days of indulgence from the Church (Beaune, 15). David’s modern appearance may be a subtle reminder to the book’s owner regarding the benefits of praying for the French king. The border illumination around the David miniature contains a crane, which symbolizes vigilance, a trait necessary for a king to have (Carr-Gomm, 239).

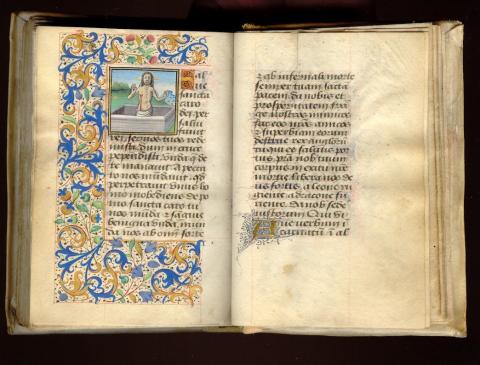

The Man of Sorrows

Christ as the Man of Sorrows appears in the next miniature. A straight-faced, bearded but not mustached Christ directly confronts the viewer with his gaze, holding up his hands to show his wounds from the Cross. He appears from the waist up, standing in a foreshortened depiction of his tomb, oddly juxtaposed against an appealing natural landscape. A strange thing about this example of the Man of Sorrows is that it seems to combine elements of the Resurrection. Christ normally appears dead and lifeless in the Man of Sorrows, because it is supposed to take place after the Deposition. In this version, Christ looks awake and alive. Worth up to 46,000 years of indulgence to anyone who prayed before the picture, the Man of Sorrows was a very popular 15th-century theme in France (Male, 96-97).

The Crucifixion

The fifth miniature is the Crucifixion. Christ is alone; John and the Virgin are not present, nor are the thieves or Romans. The Cross is set against the same ironically pretty, natural background as in the Man of Sorrows. Against a backdrop of mountains, blue sky, and trees whose leaves shimmer with gold light in the sun, Christ bleeds profusely on the cross. The Crucifixion was an easily accessible theme and was not uncommon to find in Books of Hours and other medieval art.

John the Baptist

After the Crucifixion, a scruffy and hirsute John the Baptist is introduced in a miniature wearing his camel skin garments. St. John points to a small lamb sitting on a Bible he holds with his other hand. The lamb represents Jesus, whom John referred to as "the Lamb of God" for his gentle nature and for the sacrifice he was to make (Williams, 11). Again, as with many of the miniatures, John is pictured in a natural setting on a hill. The border illumination for John includes trees, to symbolize his life of repentance and solitude spent in the wilderness. John is an appropriate addition to a Book of Hours focused on natural themes and settings.

St. Anthony Abbot

St. Anthony Abbot, a hermit-like John the Baptist, is featured in the next miniature. St. Anthony was known as "the father of monks" for being one of the earliest Christian ascetic hermits (Giorgi, 33). Anthony is represented here bearded and accompanied by a pig on a grassy knoll. He is shown in a black monk’s robe with fire at his feet, probably because he was thought to be able to cure "St. Anthony’s Fire," or shingles (Giorgi, 33).

St. Marcoul

St. Marcoul, the subject of the eighth miniature, is the third consecutive hermit saint to be represented in the Book of Hours. St. Marcoul was a French saint who left his wealth to become a solitary Benedictine monk. The French king used to pray to St. Marcoul immediately after his coronation ceremony because it was believed that through him the French king obtained the power to heal skin diseases by touch. St. Marcoul is pictured simply in his black robe holding a staff, against a bland interior setting. Peter Parshall, in his assessment of the Multnomah County Public Library’s Horae Beatae Maria Virgines, noted the rather atypical insertion of a miniature depicting St. Marcoul, a local French Benedictine saint. He suggested that this inclusion, as well as the mention of St. Vincent of Sargossa in the calendar, a saint especially honored by Benedictines, might point to patronage by a Benedictine monk (Parshall, 27).

St. Catherine of Alexandria

The next saint depicted is St. Catherine of Alexandria, who appears to be wearing contemporary masculine royal attire. She looks like a young prince, confidently holding the large black sword that was used to decapitate her, as though it were a staff. She wears a crown to represent her royal origins. She wears an elegant gold cape and stands somewhat defiantly against a richly illuminated brown and gold background. The broken wheel used to martyr her is represented on the floor in front of her. This is the only miniature besides St. Marcoul where the subject is completely indoors and no natural setting is visible. St. Catherine was imprisoned and martyred for having humiliated the emperor Maxentius by converting his 50 wise men to Christianity with her remarkable debating skills (Giorgi, 76). St. Catherine was a popular saint in France because she was viewed as having the power to protect the French against imprisonment by English invaders (Beaune, 129).

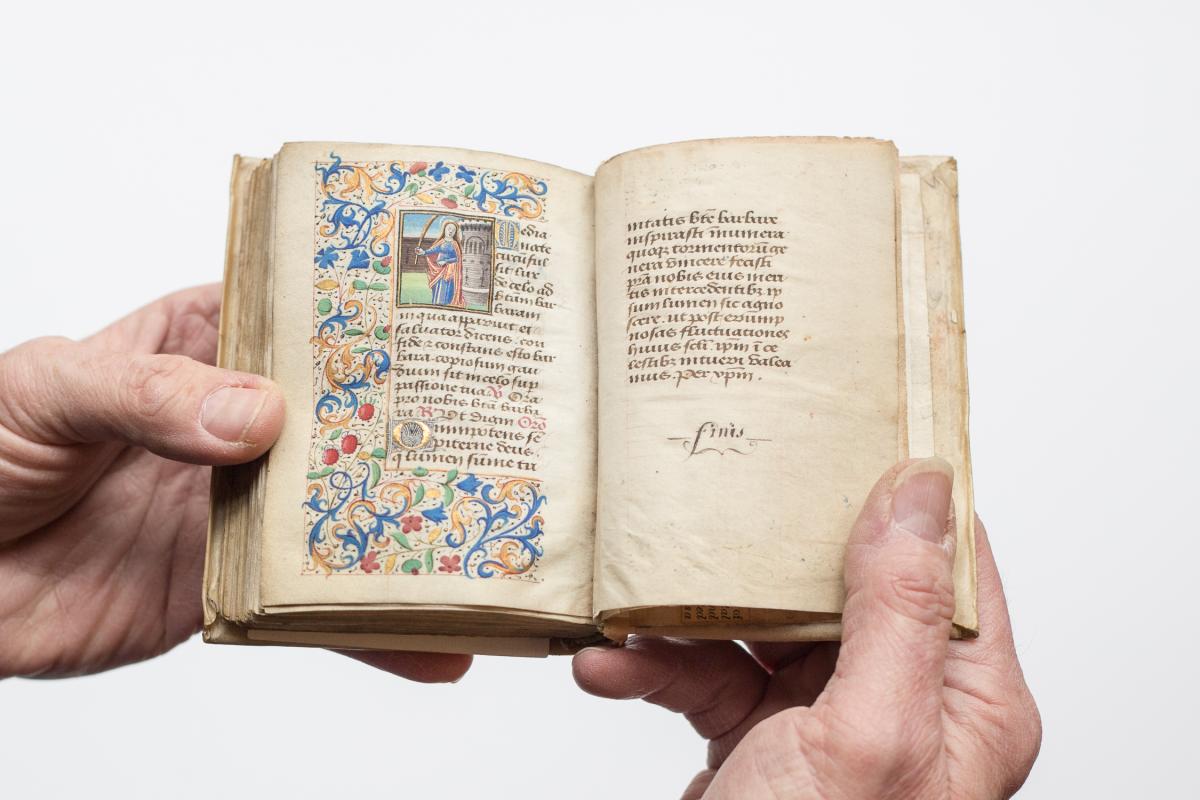

St. Barbara

The tenth and final miniature honors St. Barbara, a young saint who was murdered by her own father for converting to Christianity. Her father, king of Nicomedia, had a tower built in which to imprison his daughter to keep anyone from seeing her beauty. Barbara looked at her imprisonment as an opportunity to act as a hermit and devote herself to God. When her father discovered she had converted to Christianity, he killed her (Giorgi, 47). Barbara was a very important saint in the 15th century for her ability to protect against sudden death. As Emile Male says in his thorough study of medieval French art, "in the fifteenth century what the faithful sought, above all, was efficacious protection. Saints were honored in proportion to the powers attributed to them." (76) In light of the spontaneous recurrences of the Plague throughout Europe in the 14th through the 16th centuries, securing Barbara’s protection in one’s Book of Hours was undoubtedly a wise move.

Themes and Conclusion

This beautiful Book of Hours seems to have several themes running through it. First of all, two saints connected to the healing of skin diseases are featured at the end of the book, perhaps suggesting that the book’s patron suffered from some type of skin ailment. Secondly, only two of the ten miniatures lack a natural, outdoor background. All of the border illumination, and the historiated initials, are composed of flowers and plants and trees, and a couple of animals, with no noted elements outside of the natural world. Although the natural subject matter was common for 15th-century Northern French Books of Hours, it provides a perfect setting for its complementary theme of honoring hermits. Four out of the ten miniatures feature hermits. Such facts would seem to affirm Peter Parshall's speculation that the book was made for a Benedictine monk.

However, Christopher DeHamel notes that Books of Hours were not made for monks, but for the general public. Books of Hours were essentially short books of prayers specifically intended for individual use. Monks used larger, more complete books for worship, such as Breviaries and oversized Bibles (168). The function of portable Books of Hours was to remind the members of the laity who owned them to stay focused on God throughout their busy secular lives while they were looking after children, buying bread, making armor, etc. It is difficult to imagine that a monk, whose whole existence was dedicated to the service of Christianity, would need such a book to remind him to pray throughout the day. In fact, Benedictine monks were forbidden to own personal property, so it seems especially improbable that a monk would have owned a Book of Hours, which, in addition to being a prayer book, was a kind of vanity object (Francis, 441).

The book is also unlikely to have been made for a former monk, as medieval Benedictine monks had to swear to their profession for life ("Benedictines," 279). Given this, it seems more likely that the book was created by a monk or a group of monks at a Benedictine abbey rather than made for a monk. Benedictines were also known for their veneration and protection of books ("Benedictines," 280). Slightly wealthier and less ascetic than some other orders, Benedictines could afford the inks and vellum required to make a beautiful book of hours like the Horae Beatae Maria Virgines (DeHamel, 186). Perhaps the book was made for an "amateur hermit" who did not belong to a particular monastic order and so could venture into town on occasion and own some personal property, such as a Book of Hours. The patron could also have simply been an admirer of hermits.

Suggestions for further reading:

- Beaune, Colette. The Birth of an Ideology: Myths and Symbols of Nation in Medieval France. Trans. Susan Ross Huston. Ed. Fredric L. Cheyette. Los Angeles: University of California Press. 1991.

- Carr-Gomm, Sarah. Hidden Symbols in Art. London: Duncan Baird. 2001.

- "Benedictines." The Columbia Encyclopedia. 6th ed. New York: Columbia University Press. 2000.

- De Hamel, Christopher. A History of Illuminated Manuscripts. London: Phaidon Press. 1994.

- Francis, E.K. "Towards a Typology of Religious Orders." The American Journal of Sociology 55.5 (1950): 438-452.

- Giorgi, Rosa. Saints in Art. Trans. Thomas Michael Hartmann. Ed. Stefano Zuffi. Los Angeles: Getty Publications. 2003.

- Harthan, John. An Introduction to Illuminated Manuscripts. England: HMSO. 1983.

- Male, Emile. Religious Art in France: The Late Middle Ages. New Jersey: Princeton University. 1986.

- Post, Elwood. Saints, Signs, and Symbols. New York: Morehouse Barlow. 1962.

- "St. Marcoul." Oxford Dictionary of Saints. London: Oxford University Press. 2003.

- Williams, Caroline. Saints: Their Cults and Origins. New York: St. Martin’s Press. 1980.

- Watson, Rowan. Illuminated Manuscripts and their Scribes. New York: Harry N. Abrams. 2003.