Estienne Bible

Estienne Bible

French (Paris), 1538-40

Estienne, Robert (French printer and publisher, 1503-1559)

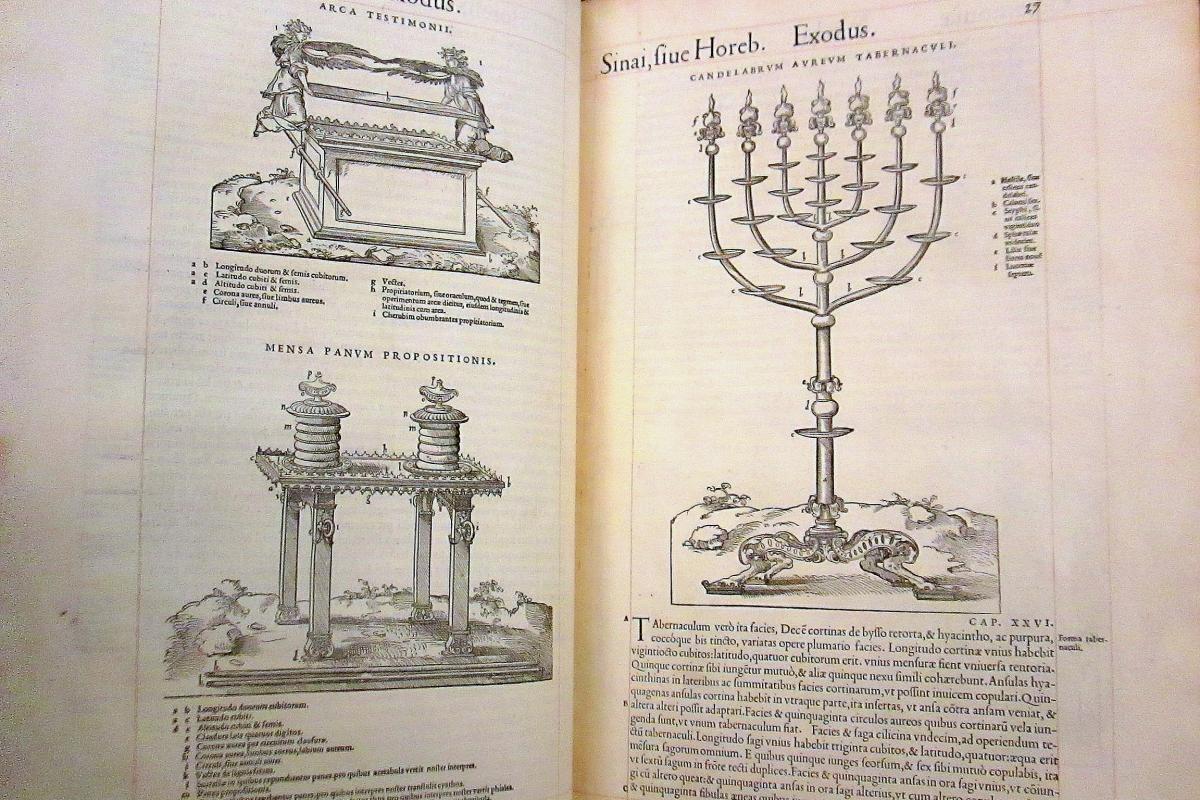

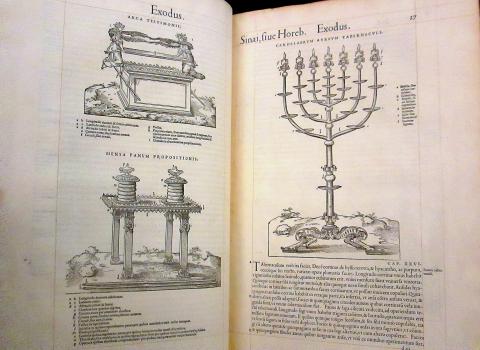

Fols. 34v-35r: Text page with Tabernacle in the Wilderness

Language: Latin

Prior Publication: Diebold, William. The Illustrated Book in the Age of Printing: Books and Manuscripts from Oregon Collections. Portland, OR: Douglas F. Cooley Memorial Art Gallery, 1993, cat. no. 38, p. 23

Diebold, William. The Illustrated Book in the Age of Printing: Books and Manuscripts from Oregon Collections. Portland, OR: Douglas F. Cooley Memorial Art Gallery, 1993, p. 23 - Quoted with permission

This large book contains an excellent text of the Bible prepared under the direction of its printer, Robert Estienne, Like Johann Froben, who commissioned and printed Erasmus's edition of the New Testament, Estienne combined Humanist scholarship with a printer's business acumen.

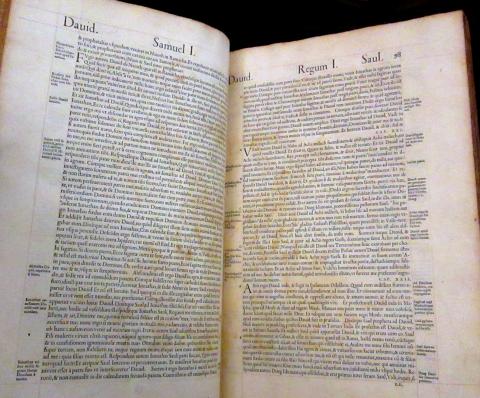

Two aspects of this Bible are particularly worthy of note in the context of this exhibition. One is the continued presence, a full century after the invention of printing, of handwork (in this instance, the ink lines which frame every page, setting off the marginal annotations from the main body of the text). The second is the large woodcut illustration on display, which shows the ark of the covenant in the wilderness, surrounded by a tabernacle. At the bottom of the illustration is a remarkable inscription in Latin which reads: "According to the dimensions given in chapter 27 of Exodus, the courtyard of the tabernacle [the reference is to the large sacred precinct set off by curtains] was rectangular, not pyramidal. That it looks pyramidal in this image, rather than rectangular, you should attribute to the artist who, however, is not to be condemned for the awkwardness of his art•here he wanted to comply with optics." This text suggests that, as late as 1540, perspective was not taken as a natural method of presenting things, but had to be explained, even to an audience sophisticated enough to be literate in Latin.

Jamila Naas, Medieval Portland Capstone Student, Summer 2014

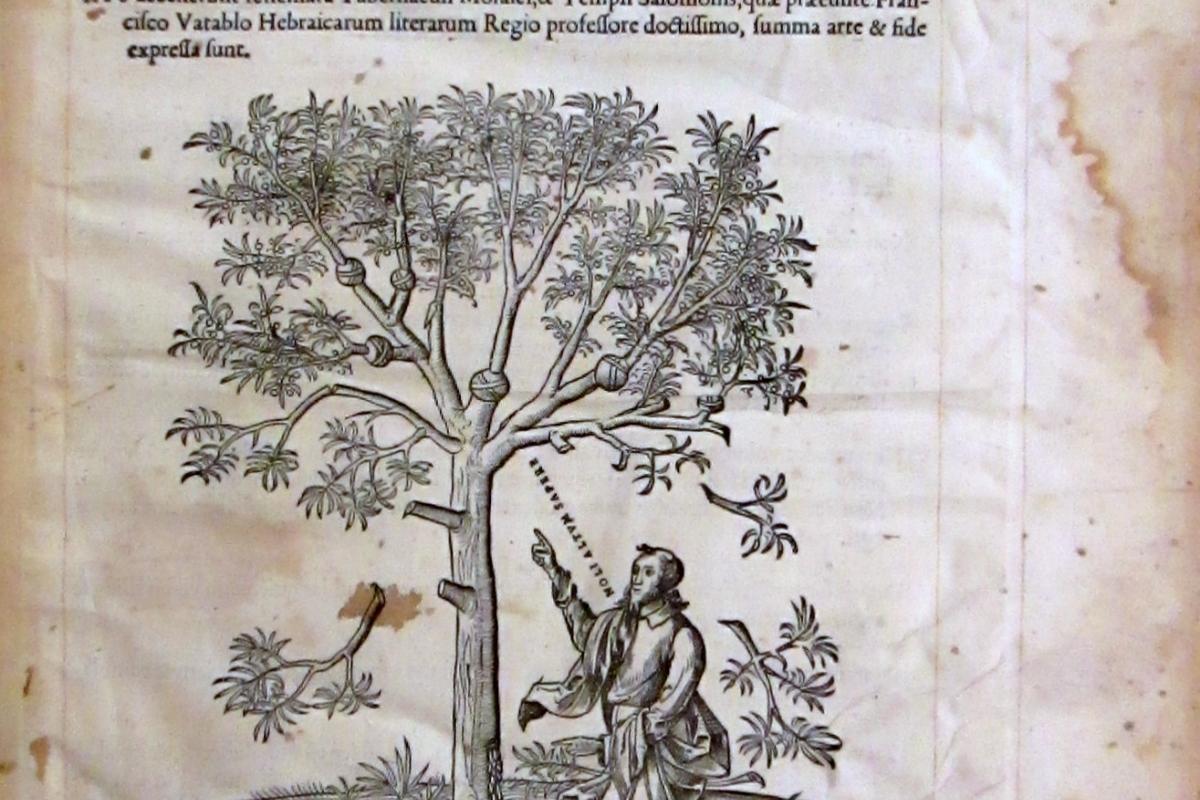

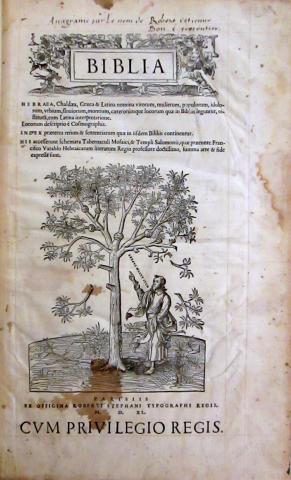

The French printer, Robert Estienne, put together a magnificent Bible, in which we can observe and appreciate a high degree of detail and care. The book was completed in 1540, one year after Estienne became the Royal Typographer for the King and adopted his well-known printer's mark of a man standing under an olive tree with the motto Noli altum sapere, sed time, or "Do not be conceited, but fear" (Armstrong 1954). While Estienne is also renowned for introducing verses to the passages of the Bible, it is important to note that he first accomplished this in the printing of the New Testament in 1551, eight years before his death (Morey 2000). Therefore, while the Bible in question is a remarkable specimen, it is not divided into verses.

The book itself features some particularly interesting physical and aesthetic attributes: after some careful scrutiny, it was discovered that the top, bottom, and fore-edge have an elaborate design gauffered onto them. Gauffering is a process in which a design is stamped into the gilded edges of a book using heated tools or special rolls (Mitchell 2010). The design appears to be a floral motif, with the word "Biblia" being legible on the top. While inscribing the title of the text on the fore-edge was common at this time and served a practical and economic purpose, this kind of intricate and decorative engraving was not as customary and certainly seems to serve no other purpose than to aesthetically please the eye. Another interesting aspect of the book is the reoccurrence of Estienne's printer's mark throughout the text; it first appears on the frontispiece, and then again near the middle to indicate a particular break in the text, such as for the start of a new chapter or book of the Bible. Besides this rather unusual practice, Estienne's printer's mark is also interestingly ostentatious and large, taking up over half the page, whereas most other printers' marks are significantly smaller and sparse in comparison. These are only a few of the many notable elements of Estienne's French Bible.

Bibliography:

Armstrong, E. (1954). Robert Estienne, Royal Printer: An Historical Study of the Elder Stephanus. Cambridge, England: Cambridge at the University Press. Retrieved June 30, 2014, from Google Scholar.

Burnett, S. G. (2000, January). Christian Hebrew Printing in the Sixteenth Century: Printers, Humanism and the Impact of the Reformation. In DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Retrieved June 30, 2014, from Google Scholar.

Chambers, B. (1977). The First French New Testament Printed In England? (pp.143-148). N.p.: Librairie Droz. Retrieved June 30, 2014, from JSTOR.

Echard, S., & Partridge, S. (Eds.). (2004). The Book Unbound: Editing and Reading Medieval Manuscripts and Texts. Toronto, Canada: University of Toronto Press. Retrieved June 30, 2014, from Google Scholar.

Farge, J. K. (1985). Orthodoxy and Reform in Early Reformation France: The Faculty of Theology of Paris, 1500-1543. Leiden, The Netherlands: E. J. Brill. Retrieved June 30, 2014

M'Clintock, J., & Strong, J. (1880). Encyclopaedia of Biblical, Theological, and Ecclesiastical Literature (Vol. 3). New York: Harper & Brothers. Retrieved June 30, 2014, from Princeton Theological Seminary Library - Internet Archive.

Mitchell, L. D. (2010, March 19). "Gauffered Edges and The Private Library." In The Private Library. Retrieved August 11, 2014

Morey, J. H. (2000). Book and Verse: A Guide to Middle English Biblical Literature (p. 174). N.p.: University of Illinois. Retrieved August 11, 2014, from Google Scholar.

Schullian, D. M. (1956, June). "Robert Estienne, Royal Printer - by Elizabeth Armstrong." In Chicago Journals. Retrieved June 30, 2014, from JSTOR.

Sneddon, C. R. (2009, December 11). "Nottingham Medieval Studies: On the Creation of the Old French Bible." In BREPOLS Periodica & Miscellanea Online. Retrieved June 30, 2014, from BREPOLS.