Madonna Surrounded by Saints | Aldobrandini Triptych

Follower of Daddi, Bernardo (Italian painter, active ca. 1280-1348)

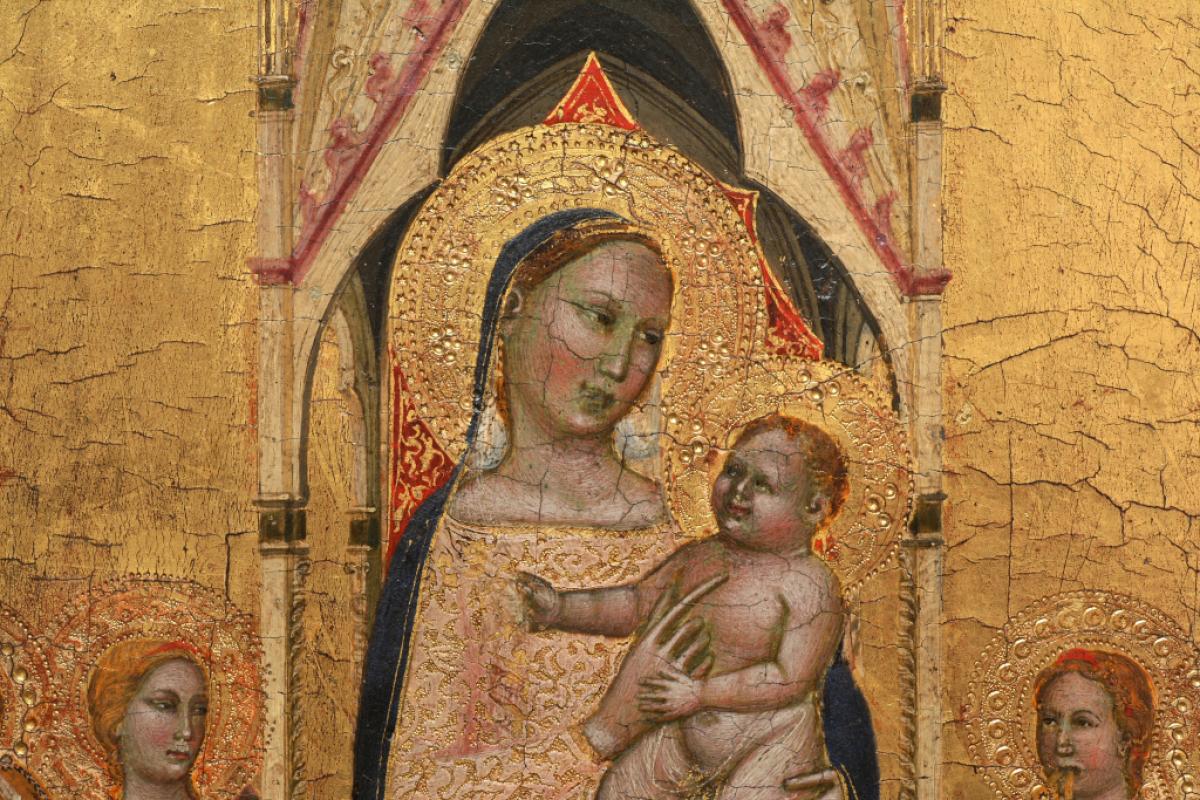

Madonna Surrounded by Saints | Aldobrandini Triptych

Italian, ca. 1336

Early Renaissance

tempera on wood panel

height 95.3 cm

width 66 cm

depth 3.5 cm

Portland Museum of Art, 61.51

Gift of Samuel H. Kress Foundation

Portland Art Museum Aldobrandini Triptych Podcast via Vimeo

Anthony Gasbarro, Katherine Bass, Kayla Linebarger, Jessa Kennedy, Medieval Portland Capstone students, Summer 2010

Kate Steinberg, Medieval Portland Capstone Student, Winter 2005

The Aldobrandini Altarpiece is a spectacular trecento Italian portable devotional work. This triptych, a panel with two hinged wings that can be opened to reveal a series of painted images, provides an example of the sort of devotional art that made up a considerable portion of the art market in proto-Renaissance Tuscany. The triptych has been attributed to the workshop of Florentine painter Bernardo Daddi (fl. ca. 1320-1348) and upon careful stylistic analyses dated to the period around 1336. The small size of the piece, and the presence of a crest on the base of the central panel, suggest that this was made for domestic devotional practice. Dr. Hofflinger, of the Austrian Institute of Genealogy and Heraldry, has identified the crest as that of the Aldobrandini family, a prominent Florentine family whose history stretches back to Roman times. The early provenance is unknown. In 1952, the triptych was purchased by Samuel H. Kress at an auction in New York; it had previously been in the Oscar Bondy Collection in Vienna.

The wooden panels were painted in egg tempera and gilded with gold leaf. The central panel shows the Virgin seated on a canopied gabled throne, holding the Christ child accompanied by Saints Paul, Margaret of Antioch, Catherine of Alexandria, Peter, Nicholas of Bari, John the Baptist, Anthony Abbot, and James the Greater. A choir of angels flanks the Virgin's throne, two on each side. Above their heads the painting dematerializes into the shimmering gold background that was characteristically used in trecento Italian panel painting, an effect carried over from Byzantine icon panels. The ornately decorated oriental carpet is laid out at the foot of the throne, providing an opportunity for the artist to demonstrate his abilities at depicting receding space. It should be noted that Florence and neighboring Lucca were centers for the production of silks and textiles in the trecento, and elaborately worked textiles became commonplace in the paintings of this time. They were often used to denote a special dress, such as that of the Virgin, and in the decoration of an interior as in this instance. An enormous amount of work has been conducted on the examination and cataloging of various painted textiles in Italian paintings of the Trecento and Quattrocento, and the motif of the horizontal palmate used here was in fact a standard motif used in the art of Bernardo Daddi and in his workshop, a fact which aids art historians in determining the authorship of unsigned and undocumented paintings. Another painted texture stands out, the simulated veined marble on the steps of the Virgin's throne, beautifully painted in pastel tones. Gold leaf has been applied to the trimmings on the garments worn by the saints, and is worked into the pattern of Mary's dress. The halos are gilded in gold and stamped with punch tools to create designs. One design is used consistently throughout the triptych for the halos of the saints and angels, and another more elaborate one is used for the Virgin and Christ.

The left panel holds a scene of the Nativity. Mary beholds her son while the traditional figures of the ox and the ass look on with an assembly of six angels. The artist deals with the narrow panel's limitations by arranging the figures on three levels, which was a typically medieval method of organizing space. The single angel above in the gold shimmering sky, along with the shepherd in prayer with his flock and Joseph in the lowest register of the panel, divides the Annunciation to the Shepherds. The right wing of the triptych renders the Crucifixion. Christ's body hangs limply on the cross encouraging an empathic response from the viewer. Atop the inscription, I.N.R.I is a pelican in her nest. At the foot of the cross, St. John supports the swooning Virgin, along with a third saint at the right and a partial figure (perhaps Longinus) accompanying them. The Annunciation takes place in the pinnacles of the two hinged wings. On the left, the Archangel Gabriel dressed in a pink robe kneels in front of a gold background wielding his traditional lily. On the opposite side, Mary is represented seated in an architectural setting, with a book in her lap, and, enveloped by a blue mantel; the holy dove comes unto her. The central panel rises to a pinnacle where God the Father appears within a tri-lobed shape. Blue and gold, the two most expensive colors, are used unsparingly here in this lavish decoration. The reverse side of the triptych is covered in gold leaf without any other figural or ornamental decoration.

Florentines commonly used the folding triptych in domestic devotional practice while the diptych seems to have been more popular with the Sienese. The format seems to have been inspired by Byzantine hinged icons. Prayers were offered through the holy icon as a sort of intermediary from the earthly world to the divine realm. Physical contact, such as touching the icon, opening it, and even kissing it, were important ritualistic aspects in the act of worshiping with the object. The teachings of Saint Francis (d. 1226) may have also given rise to the need for personal devotional images on a small scale; he launched a movement that quickly spread throughout the Italian peninsula as Christians sought a newfound humanism and personal relationship with God. Franciscans as well as the influx of Byzantine art in the early thirteenth century shaped Italian art. Improved economic and social conditions in thirteenth-century Tuscany saw a broader market for art and luxury goods, and with the rise of the mercantile class there was an increased demand for such goods, and artistic workshops arose out of this environment.

The workshop of Bernardo Daddi, to which the Aldobrandini triptych is attributed, increased their production of small-scale panel paintings. The workshop's high point of production seems to have been from 1320-1350 (Daddi likely died during the black death of 1348). There is an enormous amount of conformity in the devotional triptychs from this period, both within and outside of Daddi's workshop. The frames are mostly carved into a Gothic format; some are simpler in their design and few retain the horizontal format that was more commonly used in the thirteenth century. Also, the iconography becomes standardized. The Nativity is on the left, the Virgin and Child in the central panel, the Crucifixion on the right, with the Annunciation in the pinnacles above; Gabriel on the left, and Mary on the right.

Daddi may have received his training in Giotto's workshop, but in his mature work, he diverges from Giotto's harder lines and weighty figures and moves more in the direction of the sweet and lyrical style favored by Sienese artists. His lines are often graceful and he indulges in the delicate decorations of luxury textiles and flowery interiors. He was a great colorist and was equally as skilled in working on a small scale, Richard Offner sees this as a development of an almost "miniaturist" tendency.

It has been speculated that the primary users of these devotional panels were women. Owning such an object would allow one to worship within the confines of the home. Also, the triptychs are characterized by an abundance of Marian imagery; she appears in all three scenes as well as above, in the pinnacle, suggesting they were made for a female audience. For a patrician female, the safe delivery of a male heir was almost an obligation, and, with the perils of childbirth presenting serious dangers, an icon of the Virgin and Child could serve as a welcoming opportunity to meditate on the Virgin birth and ask for safe delivery. Saint Margaret of Antioch, who is the patron saint of childbirth, appears in the Aldobrandini triptych, reinforcing the idea that they were made for female worshipers.

Suggestions for further reading:

- Klesse, Brigitte. Seidenstoffe in der italienischen Malerei des vierzehnten Jahrhunderts. Bern: Abegg-Stiftung, 1967.

- Monnas, Lisa. "Silk textiles in the paintings of Bernardo Daddi, Andrea di Cione and their followers." Zeitschrift fur Kunstgeschichte 53 (1990): 37-58.

- Offner, Richard. Bernardo Daddi: His Shop and Following. Florence, 1991.

- ---. The Works of Bernardo Daddi, Florence, 1989.

- Wilkins, David. "Opening the Doors to Devotion: Trecento Triptychs and Suggestions concerning Images and Domestic Practice in Florence." Studies in the History of Art 61 (2002): 371-393.

Kate Steinberg, Medieval Portland Capstone Student, Winter 2005

Background Essay: Workshop production in Trecento Florence: Panel Painting

Trecento Florence saw the rise of a number of artistic workshops. Generally speaking, this phenomenon begins with Giotto, the father of Florentine Renaissance painting, who, as Vasari famously wrote, "translated painting from Greek back into Latin." Improved economic and social circumstances in the thirteenth century created a mercantile class with an increasing demand for luxury goods. Thus artistic skill was cultivated and workshops sprung up headed by a master painter or craftsman, who was aided by a number of assistants or apprentices. Among the instruction manuals and "recipe books" that pass along the techniques of the arts, Cennino Cennini's Il Libro dell'Arte, or The Craftsman's Handbook, offers the fullest descriptions of the various steps of the trecento artist's techniques of panel painting, fresco, mosaic, burnishing with gold, casting, and painting on parchment.

Panel painting was common in trecento workshops and lent itself as a perfect medium for religious works. Poplar wood was used, and it had to be carefully prepared by a carpenter. Sometimes a Gothic frame had to be fashioned by a master carpenter as well. For panel paintings, the boards would be pegged together and fastened with crosspieces on the reverse for support. The artist then sized it with several coats of glue. Better-made panel paintings included a piece of white linen over the panel to assure that the paint would not crack or split as the wood shrank and swelled with age. This separation from the panel kept the paint "floating" away from the wood and protected the painting from damage. After this stage, Cennino would instruct the artist to paint eight coats of gesso, each drying completely before it was sanded down to a smooth surface so the painting could begin. The artist most commonly made preparatory drawings in charcoal right on the prepared panel. Once the main sections were completed, a gold leaf could be applied. The panel could be sent to a goldsmith or the artist could purchase the sheets and burnish them directly onto the panel himself. Laws strictly enforced the amount of gold in each leaf; a coin the size of a dime was hammered to produce sixteen thin strips of gold leaf. Finally, the artist would take ground pigments and mix them with egg yolk to paint the image in a medium called egg tempura. Paintings would be made both under the auspices of a patron and as generic works such as devotional folding panels for which there was a large and ready market.

Suggestions for further reading:

- Cennini, Cennino. The Craftsman's Handbook. Trans. Daniel V. Thompson, Jr. Dover: New York, 1960.

- Thomas, Anabel. The Painter's Practice in Renaissance Tuscany. Cambridge University Press, 1995.