Nuremberg Chronicle Leaf | Liber Chronicarum Leaf

1493

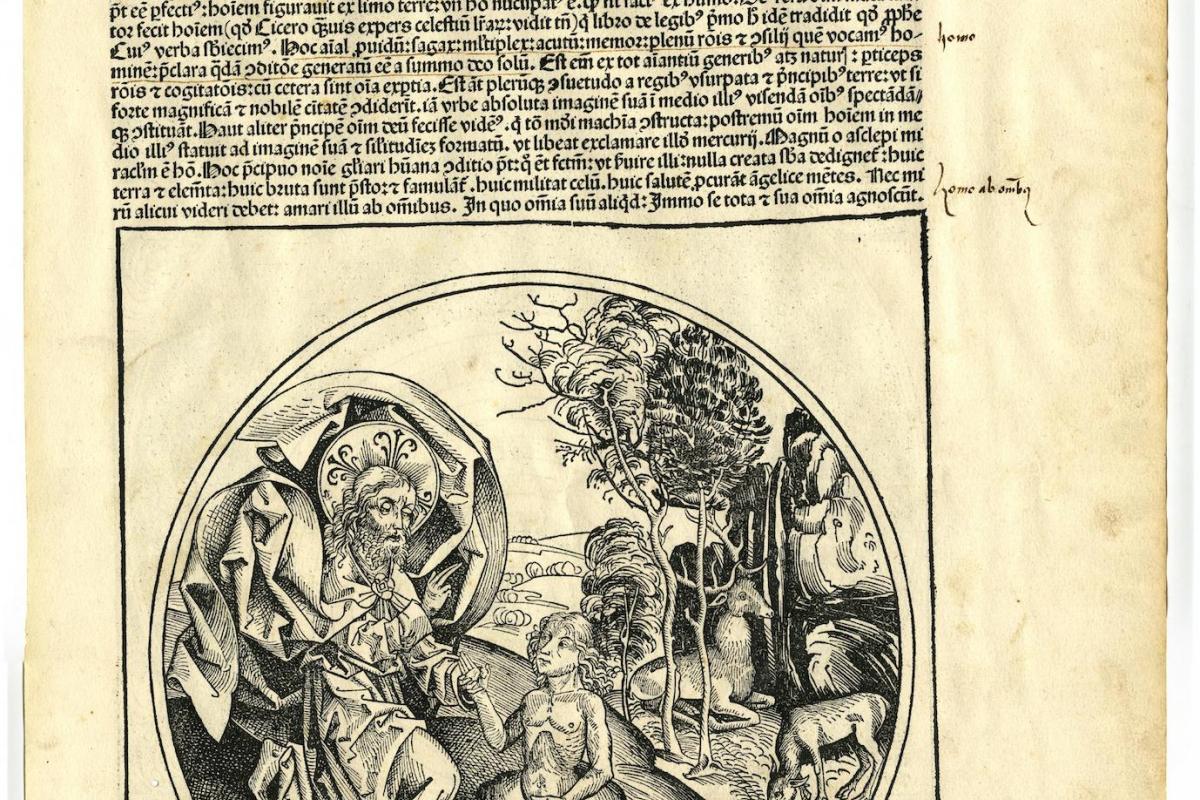

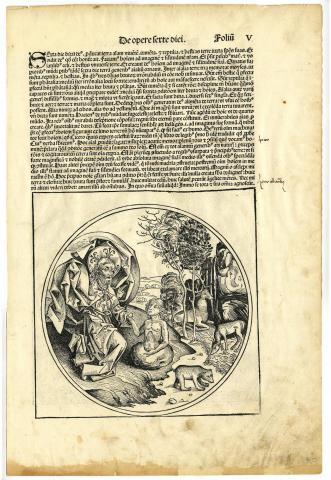

Recto: 6th day of Genesis: Creation of Adam and Creatures of the Earth

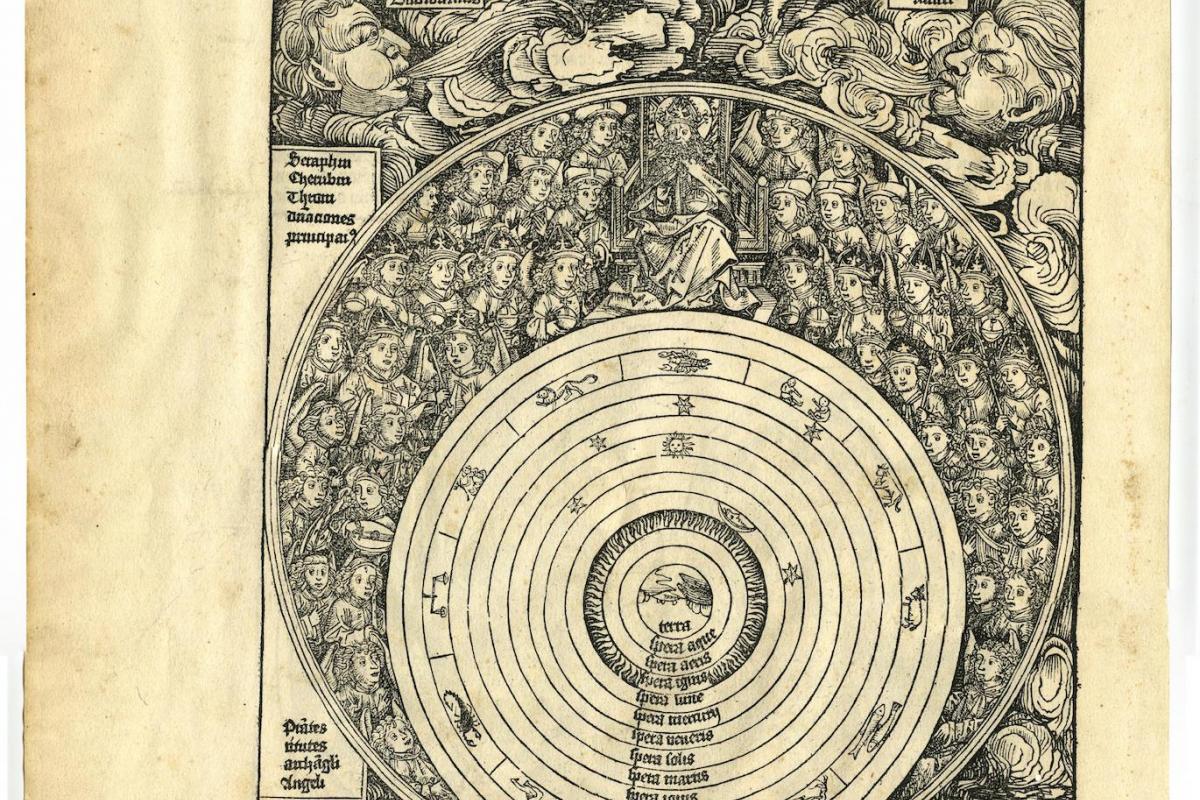

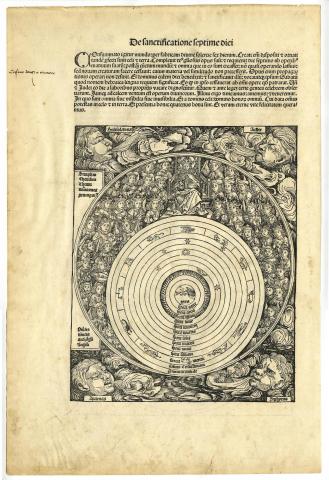

Verso: 7th day of Genesis: God and Angels Looking at the Universe

Printed in Nuremberg, Germany

Language: Latin

height 47 cm | width 31.5 cm

Reed College Library Special Collections, Gift of Lloyd Reynolds

Reed College Special Collections Early Printing and Writing Entry

Rebekah Ladizinsky, Medieval Capstone Student, Spring 2016

The Nuremberg Chronicle was written in Latin by Hartmann Schedel (1440–1514), a Nuremberg physician, humanist, and collector of books. The text was later translated into the vernacular by Georg Alt (1415-1510), a city treasury scribe and humanist fellow of Schedel. Both versions of the Chronicle were published in 1493 by Anton Koberger (1440/45-1513), the owner of the largest printing house in the Holy Roman Empire at the time of publication, and first to be established in Nuremberg. The original text, translation, illustrations, and publication of the Chronicle were commissioned by Nuremberg merchants, Sebald Schreyer (1446-1520) and Sebastian Kammermeister (1446-1503).[1]

The Nuremberg Chronicle is the most ambitious printing venture of late 15th-century incunabula.[2] It is notable not only for its content; a compiled history of the Christian world according to both biblical and secular accounts, but also the survival of the original manuscript, some preliminary sketches for illustrations, and complete layout plans.[3] This information shows modern viewers how early printers may have planned and designed their books.

This leaf, housed in the Reed College Special Collections, is the fifth page of the Nuremberg Chronicle. It contains the last two panels from the first of the Chronicle’s eight sections.

The recto details the sixth day of creation based on the biblical account of creation. It includes a full illustration of God as a robed male figure helping Adam emerge from a rock. A translation of the Latin text reads, “He [God] formed man of the dust of the ground (ex humo) hence he is called human”[4] The illustration is framed by a double circle and a square, these symbols are used to represent divine materialization. Representations like this were likely inspired by the series of circles shown at the opening of the Cologne Bible of Quentell written in 1480.[5] According to the surviving preliminary sketches for the layout of the Chronicle,[6] the woodcut artist of this panel appears to have not followed the plan for this illustration. Instead, he has included flora and fauna that were not indicated in the original proposal for this page.[7]

The verso depicts the seventh, final day of creation. The panel features a large and intricate illustration of God, again as a robed male figure, as well as many faces of angels looking upon the universe which is symbolized by labeled spheres or circles. The landscape at the center of the spheres is pictured upside down to indicate planetary movement.[8] Zodiac symbols line the interior of an outward sphere. The scene is enclosed by personifications of the four winds at each corner of the frame. The artistic style of this panel is strikingly different from that of the book’s previous illustrations. This can be attributed to mastery of the panel’s woodcut artist, a young Albrecht Dürer, who contributed several illustrations to the Nuremberg Chronicle.[9] Dürer, the Nuremberg-born godson of Anton Koberger sustained a correspondence with major Italian artists including Leonardo da Vinci and Raphael after traveling to Italy as a youth.[10] Through his work, Dürer introduced Italian Renaissance models to his homeland.[11]

Notes:

[1] Zahn, Peter. The Making of the Nuremberg Chronicle. 2nd ed. Amsterdam: Nico Israel, 1978. (Introduction)

[2] Green, Jonathan. The Nuremberg Chronicle and Its Readers: The Reception of Hartmann Schedel's Liber Chronicarum. 2003. (3)

[3] Wilson & Wilson. The Making of the Nuremberg Chronicle. (94)

[4] Wilson, Adrian, and Joyce Lancaster Wilson. The Making of the Nuremberg Chronicle. 2nd ed. Amsterdam: Nico Israel, 1978. (81)

[5] Wilson & Wilson. The Making of the Nuremberg Chronicle. (81)

[6] Wilson & Wilson. The Making of the Nuremberg Chronicle. (94)

[7] Wilson & Wilson. The Making of the Nuremberg Chronicle. (92,93)

[8] Wilson & Wilson. The Making of the Nuremberg Chronicle. (97)

[9] Reske, Christoph, Die Produktion der Schedelschen Weltchronik in Nürnberg, Mainzer Studien zur Buchwissenschaft vol. Bd. 10. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2000 (4)

[10] Reske. Die Produktion der Schedelschen Weltchronik in Nürnberg, Mainzer Studien zur Buchwissenschaft vol. Bd. 10. (6)

[11] Wolf, Norbert. Albrecht Dürer. Munich: Prestel, 2010. (24)

Bibliography:

Green, Jonathan. “The Nuremberg Chronicle and Its Readers: The Reception of Hartmann Schedel's Liber Chronicarum”. (PhD Dissertation, University of Illinois) 2003.

Reske, Christoph, Die Produktion der Schedelschen Weltchronik in Nürnberg, Mainzer Studien zur Buchwissenschaft vol. Bd. 10. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2000.

Rücker, Elisabeth, Die Schedelsche Weltchronik- Das größte buchunternehmen der Dürer-Zeit. Munich: Prestel, 1973.

Schedel, Hartmann. "Treasures of the Library: Nuremberg Chronicle." Cambridge Digital Library. University of Cambridge. Web. 10 Apr. 2016.

Wilson, Adrian, and Joyce Lancaster Wilson. The Making of the Nuremberg Chronicle. 2nd ed. Amsterdam: Nico Israel, 1978.

Wolf, Norbert. Albrecht Dürer. Munich: Prestel, 2010.

Zahn, Peter. The Making of the Nuremberg Chronicle. 2nd ed. Amsterdam: Nico Israel, 1978.