Psalm Commentary

Psalm Commentary

French, 13th century

Author: Petri Lombardi, Bishop of Paris, ca. 1100-1160

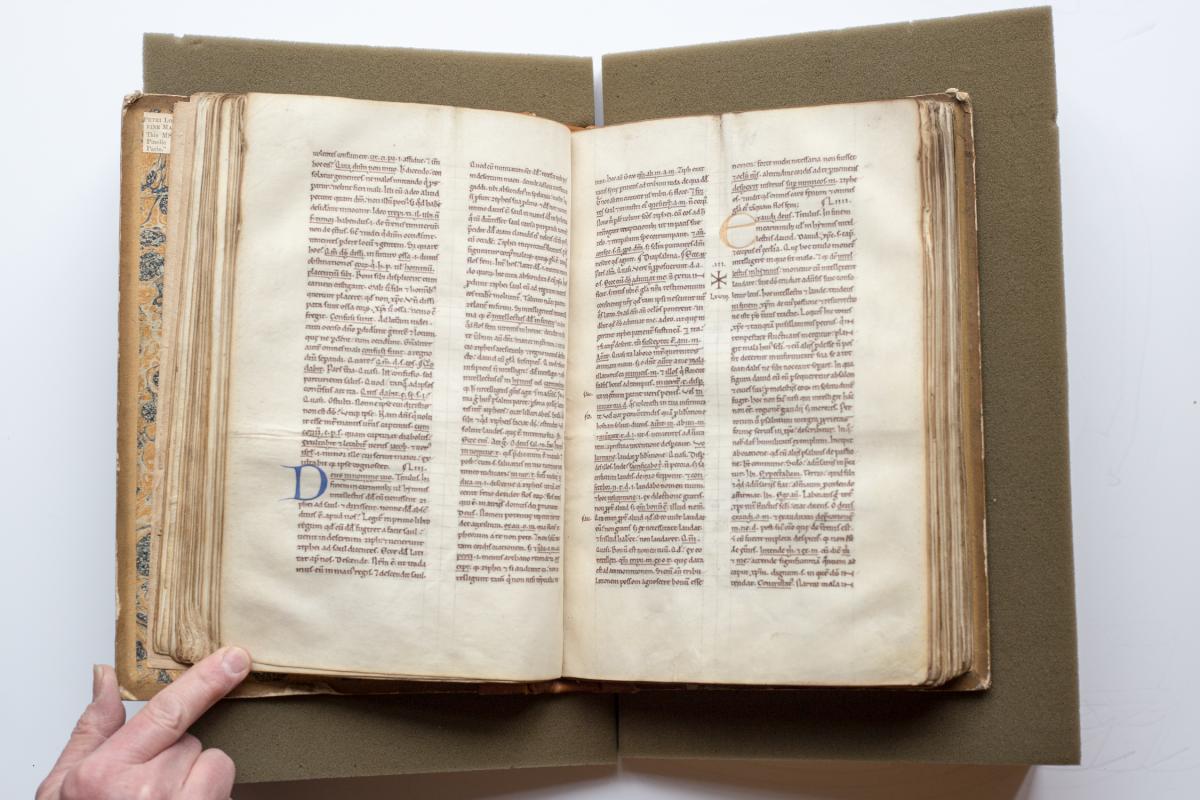

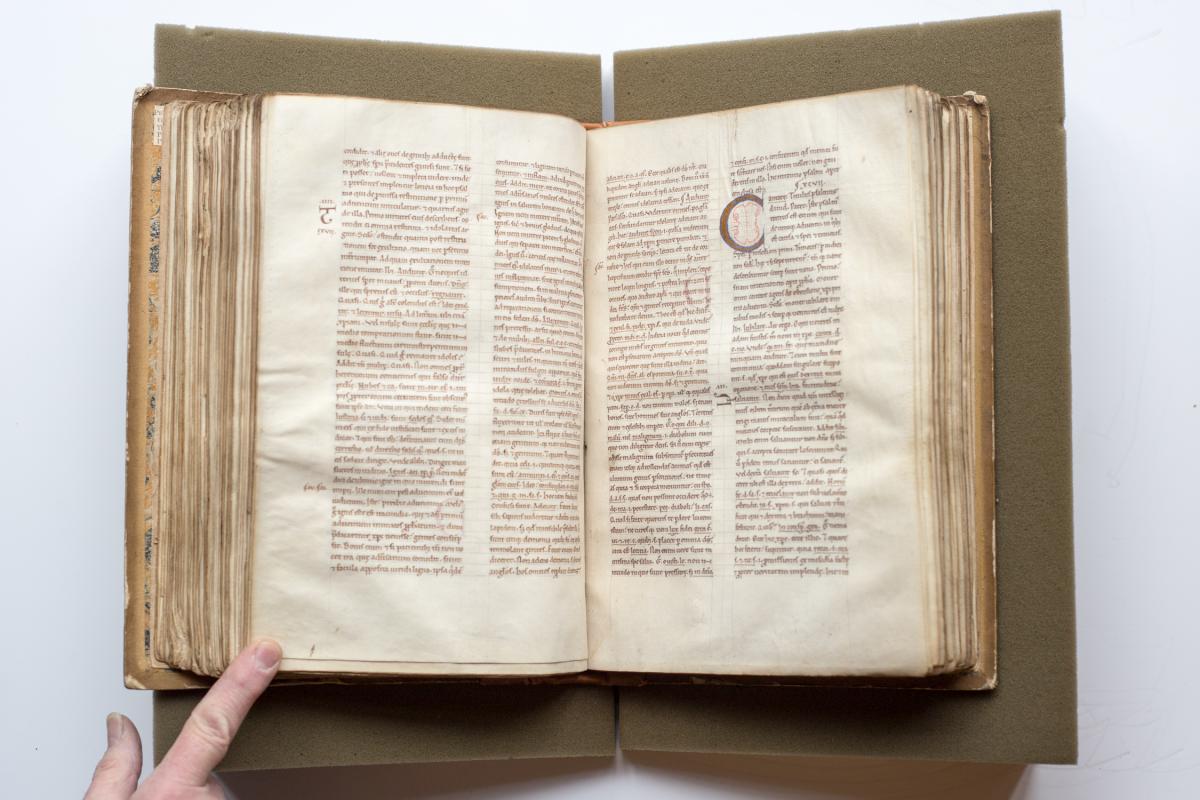

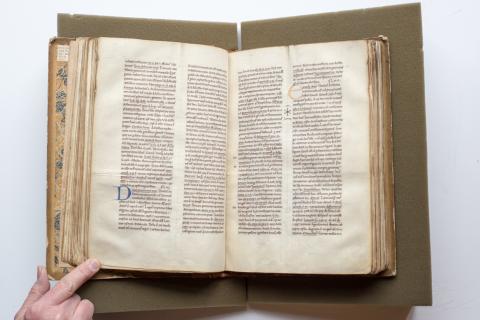

On vellum with some pricking visible

18th-century repaired binding

height 28 cm

width 20 cm

Petrus Lombardus, In Psalmos. Vel. (XIVth c.), 191 ff. (28 x 20 cm.). Modern binding. Former owner: Ludovicus Pinelle, Magister Principalis Regales Collegii Navarrae, of Paris. - Obtained (20 Nov. 1890) from B. F. Stevens.

Quoted from Seymour De Ricci, with the assistance of W. J. Wilson, Census of Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts in the United States and Canada, II, New York: The H. W. Wilson Company, 1937, p. 125.

Rose LaCroix, Medieval Portland Capstone Student, 2015

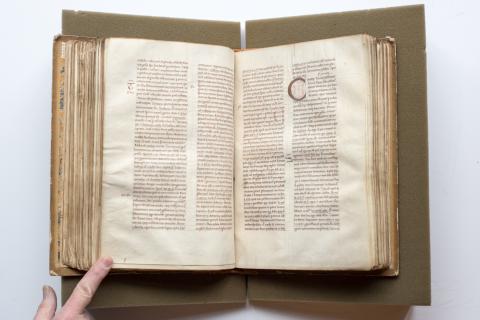

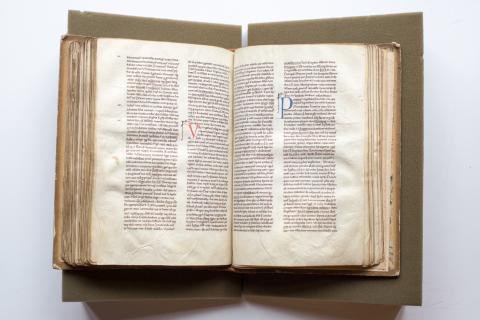

Commentarius In Psalmos was an early work by Peter Lombard that was among the founding works of scholastic exegesis of the Middle Ages. It was one of the most frequently copied and studied works of its kind in 12th-century theological schools (Colish, 531-532). Peter Lombard (ca. 1095-ca. 1160) was a 12th Century theologian, and this particular copy of Lombard's Commentarius consists of about 189 leaves of low-quality vellum displaying many natural holes and flaws, bound in a later (probably 19th c.) leather binding with paper boards and hand-marbled endpapers. The binding displays dings and substantial edge wear, and the leaves display evidence of biopredation in the form of wormholes, as well as staining on the outermost leaves. In places pigments from the capitals, particularly those initials rendered in green, appear to have bled through the vellum. This is probably due to the use of corrosive pigments such as verdigris, which were made with copper oxides in an acidic solution and are known to attack vellum (Clemens and Graham, 27). The innermost pages are generally in excellent condition aside from this probable corrosion. The vellum is still supple and retains much of its original color on the inner pages, and many of the scribe's original pencil marks, including page ruling and placement marks for the initials, can still be clearly seen on a number of the interior pages. In all the book appears to have seen minimal use during its long history.

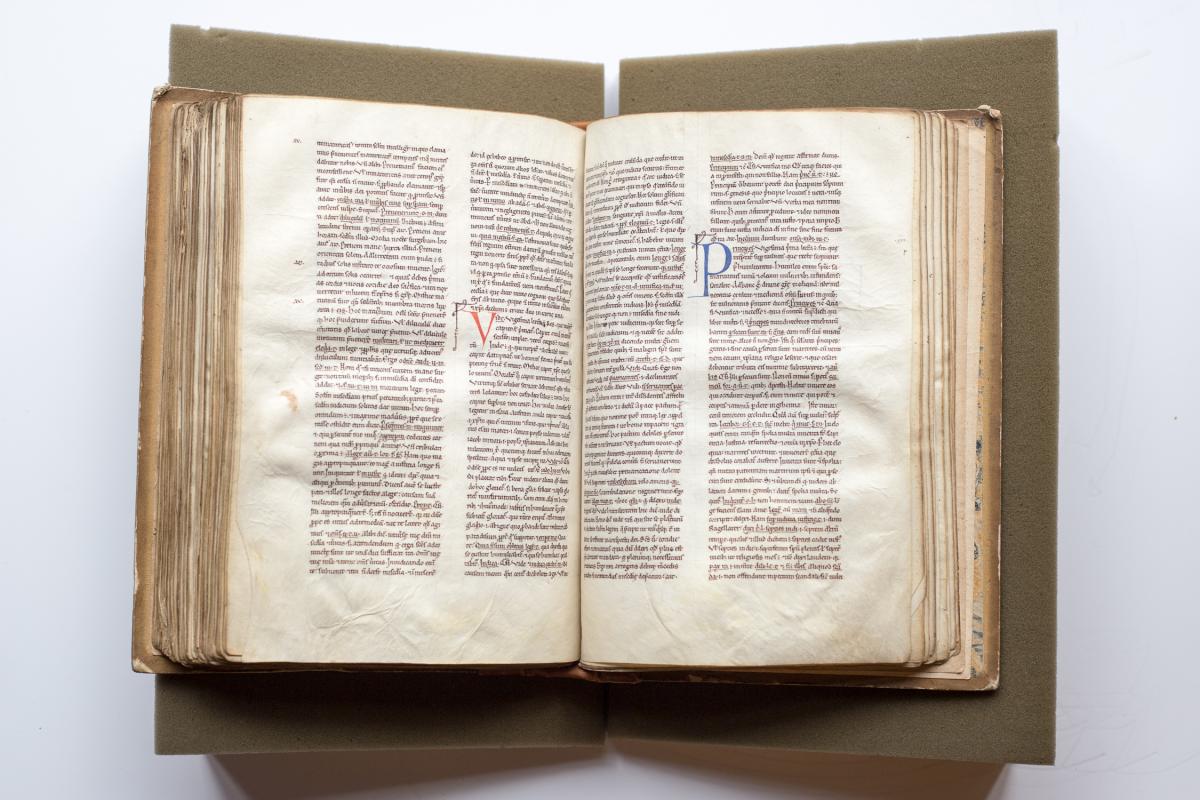

The pages display a handful of illuminated initials along with a large number of initials in red, green, and blue. The book contains few marginalia and is completely without miniatures but the pages are entirely legible throughout. The illumination has a lumpy, uneven, and brush-stroked appearance, suggesting that it is not real gold but rather a cheaper gold substitute, tin disulfide, also known as "Mosaic Gold" (Clemens and Graham, 34). The top of the first page contains an inscription in block capitals that reads "SCI SPC ASSIT NOBIS GRATIA" where "SCI SPC" stands for "Sanctus Spiritus" (Clemens and Graham, 93). A colophon at the end, written in a different script and darker ink, identifies it as the property of one "Ludovici Pinelle."

Along with a Multnomah County Library sticker and a bookplate identifying the book as part of the John Wilson collection, there is a label pasted inside that reads "Petri Lombardi Commentarius In Psalmos, Fine Manuscript In Vellum, Saec. XIII. This MS. was formerly in the possession of 'Ludovici Pinelle Magistri Principalis Regalis Collegii Navarre Paris'" in reference to the colophon.

This pasted label appears to have been cut from an 1871 Sotheby's auction catalog for the sale of the estate of one Joseph Lilly, which has an identical entry (p. 211). Joseph Lilly (1804-1870) was an English bookseller of some note who opened his first shop in 1831. Among the books, Lilly is known to have sold during his career were several copies of Shakespeare's First Folio ("Dorman Library Sale Catalogue," 121-122).

Prior to 1870 very little is known about the text's provenance. A possible match for "Ludovici Pinelle" is Louis Pinelle, Bishop Emeritus of Meaux, France. He served as bishop from 1511 to 1515 and died in January 1516 ("Hierarchia Catholica," 240). No information about his service as headmaster of the College of Navarre or how he came to possess this manuscript has been found. The grant to build the Royal College of Navarre at Paris was not given until 1304 (Schachner, 143) and the college itself was not founded until 1309 (Sanchez-Marco), which means that even the latest date given for this manuscript (ca. 1299 according to the library catalog) predates the college by a decade.

The 13th-century date given for this particular text, which appears to be based solely on the entry from the auction catalog and on no other evidence, is questionable in light of several key physical aspects of the manuscript itself. The pages display rule pricking on only one side of the margins, a trait typical of books before the mid-12th century or after the mid-13th Century (Clemens and Graham, 16). However, a late 13th Century date is unlikely as the text appears to be written in a late Caroline Protogothic script that vanished after the early 13th Century (Clemens and Graham, 147). The prickly, angular style of the text and the elongated "feet" on the minims suggests an Insular Protogothic style typical of centers in the southeast of England, such as Canterbury, prior to about 1140 (Brown, 76-77). All of the colored initials except one lack the contrasting pen flourishes typical of the 13th century (Clemens and Graham, 27), suggesting this lone initial may be the work of a later scribe embellishing an existing text. Furthermore, we know that Commentarius In Psalmos was written sometime before 1138 (Colish, 532). This narrows the likely date of the manuscript to some time between 1138 and 1150.

The lack of clear library or shelfmarks, the relative lack of marginalia, the complete absence of miniatures, the colophon dating from the Renaissance (by which point the book was already several hundred years old), and the widely-distributed Protogothic text style make decisive dating and provenance for this particular manuscript nearly impossible.

Given the rough quality of the vellum, the likely use of "Mosaic Gold" for illuminations, and the lack of any illustrative miniatures, this particular manuscript was probably not intended for a wealthy client such as an archbishop, an abbey, or a member of the nobility. If we consider a possible 12th-century date, this particular copy may have been owned by a school library that jealously guarded its texts or by a teacher working on a limited budget. During the 12th century, books such as this were so rare that scholastic methods were often reduced to hair-splitting analysis and paraphrasing, and students almost never owned their own copies of a text (Compayre, 184-186). A book this size might take six to eight months for a scribe to prepare in those days and would have been prohibitively expensive for most people (Daly, 4). While some copies of useful texts were loaned to students for a fee well into the 13th century (Haskins, 51-53), the relatively good condition and lack of marginalia suggest that this copy saw limited use and was probably not on loan to students at any time in its long history.

In an age when some textbooks were embellished with such frivolities as "baboons and gold lettering" (Rouse and Rouse, 103), this manuscript is an excellent surviving example of the sort of text that was probably more common in the 12th and 13th centuries. While baboons and gold lettering might excite collectors and antiquarians, plain texts like this example are an important part of the history of the book as an object because they show us the sort of books that were typical of the early universities.

Works Cited

Brown, Michelle P. A Guide To Western Historical Scripts. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1990. Print.

Catalog of the First Portion of the Entire Valuable & Extensive Stock of Rare, Curious, And Important Books and Manuscripts, The Property of the Late Mr. Joseph Lilly, The Eminent Bookseller. Long Acre: Dryden press, 1871. Web. 23 April 2015.

Clemens, Raymond, and Timothy Graham. Introduction to Manuscript Studies. New York: Cornell University Press, 2007. Print.

Colish, Marcia. "Psalterium Scholastocorum: Peter Lombard and the Emergence of Scholastic Psalms Exegesis." Speculum 67.3 (1992): 531-538. Web. 23 April 2015.

Compayre, Gabriel. Abelard and the Origin and Early History of Universities. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1901. Print.

Daly, Lowrie J. The Medieval University. New York: Sheed and Ward, 1961. Print.

Haskins, Charles H. Rise of Universities. New York: Peter Smith, 1940. Print.

Hierarchia Catholica Medii Aevi: III (1503-1592). Regensberg: Library of the Monastery of Regensberg, 1923. Web. 23 April, 2015.

"Peter Lombard (1095-1160)." Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. n.p. n.d. Web. 16 May 2015.

Piltz, Anders The World of Medieval Learning. Trans. David Jones. Totowa: Barnes and Noble, 1981. Print.

Rouse, R.H. and M.A. Rouse. "The Commercial Production of Manuscript Books In Late Thirteenth And Early Fourteenth Century Paris." Medieval Book Production: Assessing The Evidence. Los Altos Hills: Anderson-Lovelace, 1990. Print.

Sanchez-Marco, Carlos. "Historia Medieval del Reyno de Navarra." Lebrel Blanco. Fundación Lebrel Blanco, 2005. Web. 29 May 2015.

Schachner, Nathan. The Mediaeval Universities. New York: Perpetua, 1962. Print.

The Rushton M. Dorman, Esq. Library Sale Catalogue (1886): The Study of the Dispersal of a Nineteenth-Century American Private Library. Ed. Samuel J. Rogar. Lewiston: Edwin Mellen Press, 2002. Web. 23 April, 2015.