Abbasid Qur'an Leaf in Kufic Script

Podcast: Abbasid Qu'ran Description

This podcast was researched and written by Jeffry Brown, PSU student

Part of the Gift of the Word exhibition, Portland State University Library, Spring 2012

Abbasid Quran Description Jeff Brown.mp3, by mcclanan

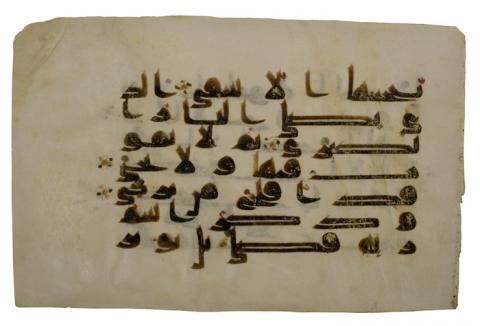

Leaf with Surah (Al-A'la), verses 11-15 (verso), verses 16-19 (recto)

Islamic, 10th century

Near East or North Africa.

ink on vellum

height 13 cm | width 20 cm

Portland State University Library Special Collections, Mss. 36

----------

Jeffrey Brown, Medieval Portland Capstone Student:

This manuscript bears many of the hallmarks of the Qur'anic manuscript tradition of the late ninth and early tenth centuries CE. This style of Kufic script, termed by renowned Islamicist Francois Deroche as "mature Abbasid," was widely employed from the mid-ninth through mid-tenth centuries, during the height of the Abbasid dynasty (750-1258 CE).[1] Despite the development and common use by the ninth century of a system of diacritical markings that aided the reading of Arabic, only one instance of letter pointing can be found in this present example (in the second line).[2] Vocalization, the indication of specific vowel sounds, is aided by red and green dots throughout the text. It is difficult to know with certainty whether these marks are original to the script, as many contemporary texts minimized the use of letter pointing and vocalization markers in favor of an overall aesthetic of austerity.[3]

The provenance of this manuscript is difficult to trace, although the style of Kufic resembles that of other contemporary manuscripts produced in Syria and Egypt. The ruling of the script is only slightly imperfect, indicating a practiced and competent hand. The exaggerated horizontal stretching of Arabic characters, known as mashq, appears on every line except for the first. The horizontality of the script is punctuated intermittently by the sweeping verticality of some characters, several of which cross into neighboring lines of text. Characters are evenly spaced, providing a sense of regular rhythm to the script. However, the seven lines of text appear rather tightly packed, giving the sense of a compact block of text, the dimensions of which bear the same geometrical ratio (2:3) to those of the page. The scribe's use of mashq to elongate certain words coupled with the arrangement of the text suggests a conscious attempt to achieve a unified geometric aesthetic. Many early Qur'anic texts from the eighth and ninth centuries demonstrate similar sensitivity to geometrical ratios.[4]

Verses are separated by a kind of floral rosette composed of red and green dots with an extremely fine line of brown ink linking each to a central gold dot. The fineness of the lines and the shape and color of these dots - especially the tint of green used - suggests that these were made by a different pen than that used to execute the script. Another gold element, surrounded also by a fine line in brown pigment, appears in the last line of the text on this page. Resembling a lowercase "a" in the English alphabet, this is the Arabic character ha, which was commonly used as a fifth verse marker in Qur'anic manuscripts from this period: in this case, the ha denotes the end of the fifteenth verse of Surah 87. These decorative markers seem to interrupt the even spacing between words; two lie completely outside the formal rectilinear grid created by the text. The characteristics of these verse markers strongly suggest that they were added at a later time.

Therefore this appears to be a Qur'anic manuscript that was executed in two distinct stages. The original text was written according to a convention common to the late ninth century: one that favored an aesthetic of austerity through abstraction over legibility. At some later point, elaborated verse separators and perhaps some additional diacritical markers were added to assist the reader, thereby enhancing the functionality of the manuscript. This particular manuscript may have come from a type of prayer book known as a juz', a single volume in a set of thirty - one for each day of the month - that comprised a complete edition of the Qur'an.[5] If so, it is tempting to consider how a pious Muslim might have appreciated and used this text over a thousand years ago to contemplate the power and majesty of the Divine.

NOTES:

[1] Francois Deroche, The Abbasid Tradition (New York: Oxford University Press, 1992), 34-35.

The term Kufic derives from the city of al-Kufah, in modern southern Iraq, but examples of this script can be found in manuscripts from all throughout medieval Egypt, Syria, and Mesopotamia. See also Widjan Ali, The Arab Contribution to Islamic Art: From the Seventh to the Fifteenth Centuries (Cairo: American University in Cairo Press,1999), 79.

[2] Martin Lings, The Quranic Art of Calligraphy and Illumination ( London: World of Islam Festival Trust, 1976), 18.

Francois Deroche, Islamic Codicology: An Introduction to the Study of Manuscripts in Arabic Script (London: Al-Furqan Islamic Heritage Foundation, 2006), 222-24.

Marcus Fraser and Will Kwiatkowski, Ink and Gold: Islamic Calligraphy (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2006), 25-26.

[3] Fraser and Kwiatkowski, 39-40.

For contemporary manuscripts of similar script style and execution, see Fraser and Kwiatkowski, 30-51, and Deroche, The Abbasid Tradition, 67-107. In particular, see Deroche, The Abbasid Tradition, 97, for another manuscript that contains these same verses of Surah 87.

[4] Deroche, Islamic Codicology, 169-171.

See also the later Qur'anic manuscript from this current collection for this attention to geometrical and mathematical ratios.

[5] Fraser and Kwiatkowski, 49.

----------

STUDY GUIDE

Rachel R. Correll, Sophomore Inquiry Mentor Session Project, Spring 2012

The Object

This is one leaf, or page, from a late ninth or early tenth century Qur'an manuscript and includes ten verses from chapter (or Surah) 87. It measures 13 by 20 cm, and includes text in black ink and ornamentation with gold leaf and red and green inks. Muslims believe the Qur'an contains text that was first revealed to the prophet Muhammad by the angel Gabriel from 610-632 CE. The verses contained in the Qur'an, therefore, are direct words of Allah (God), and are thus treated as sacred. It is likely it was from a juz', which is a prayerbook that comprises one volume in a set of thirty that include all of the text of the Qur'an. The style of the script in the leaf points to its origin in either Syria or Egypt, perhaps in one of the larger manuscript production centers such as Cairo or Damascus. It was made during the Abbasid dynasty (750-1258 CE), which covered the north coast of Africa and a large portion of the modern Middle East. The Abbasids were ruled by Islamic caliphs and Islam experienced a Golden Age during this period of rule in which art, literature, and science flourished.

The Text

The Arabic text (read right to left) is written in Kufic script, which was a majestic, condensed script commonly used in Qur'anic manuscripts in this period. It is characterized by angular and thick lines. In this example, there is a stretching of the characters horizontally in nearly every line, a technique which is called mashq. This is balanced by the verticality of some of the other characters. Clearly a conscious effort on the part of the scribe, mashq is evidence of an attempt to achieve an overall geometric aesthetic in the text and its relationship to the pages. There is a 2:3 ratio in the size of the text block versus the dimensions of the page itself. There are seven lines of text that are written quite compactly and are only interrupted by decorative markers in the margins. The red and green dots above some of the letters are vocalization markers to aid the reading of the words. The text is from Surah 87: "The Most High" which advises against the dangers of living a worldly life, ignoring salvation as it is written in the Qur'an. The text was written closely adhering to the conventions of late ninth century calligraphy in which abstraction was valued over legibility as it promoted an aesthetic of austerity. This is clearly seen in the use of the Kufic script which is more difficult to read than other Arabic scripts because of its condensed, geometric nature.

Ornamentation

As Islam does not allow the representation of objects or figures in its art, the only decorations in this leaf are floral rosettes that serve as single-verse markers. It is thought they were not executed in the same hand as the script but added at a later date because they interrupt the geometrical integrity of the page. There is also a fifth-verse marker at the bottom of the page on the reverse that denotes the end of the fifteenth verse. It is the Arabic letter ha and was commonly used in Qur'anic manuscripts of this period as the fifth-verse marker. These indicators were likely added at a later date to increase the usability of the text.

Source: Jeff Brown, "Qur'an leaf in Kufic script," The Gift of the Word, catalog, Spring 2012 exhibition, Portland State University Millar Library Special Collections.

Inquiry

As the Qur'an is considered to be the direct transcription of the words of Allah himself, why do you think it would be important to make the calligraphy and embellishments as perfect as possible? Besides promoting a geometric aesthetic on the page, what are other effects the mashq technique? Does this technique successfully fill in blank spaces in lines? How do you think this affects reading and scanning of the text? What do you think are some of the benefits of using verse markers in the margins and between the lines of text? How would you describe the Kufic script and what characteristics make it seem like it would be hard to read?"