Bible Leaf

Bible Leaf

French, ca. 1215

Language: Latin

Artist/Author: Peter Lombard, Bishop of Paris

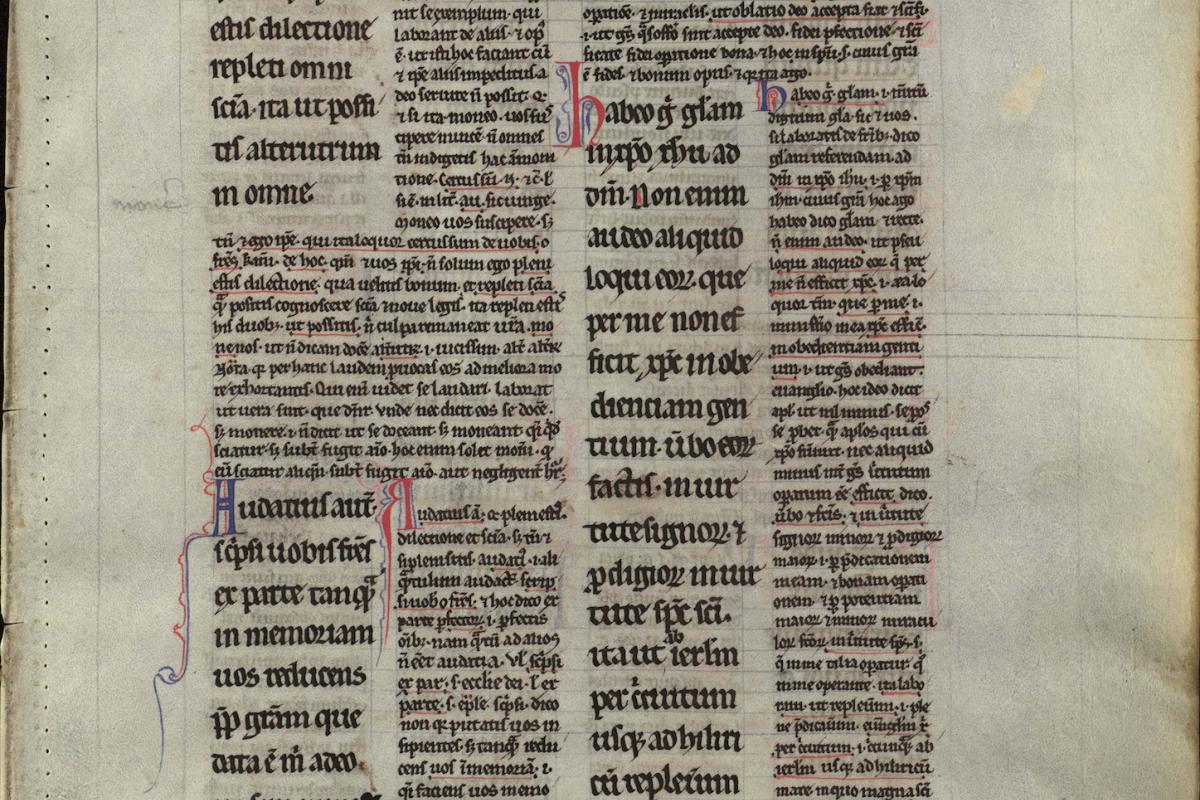

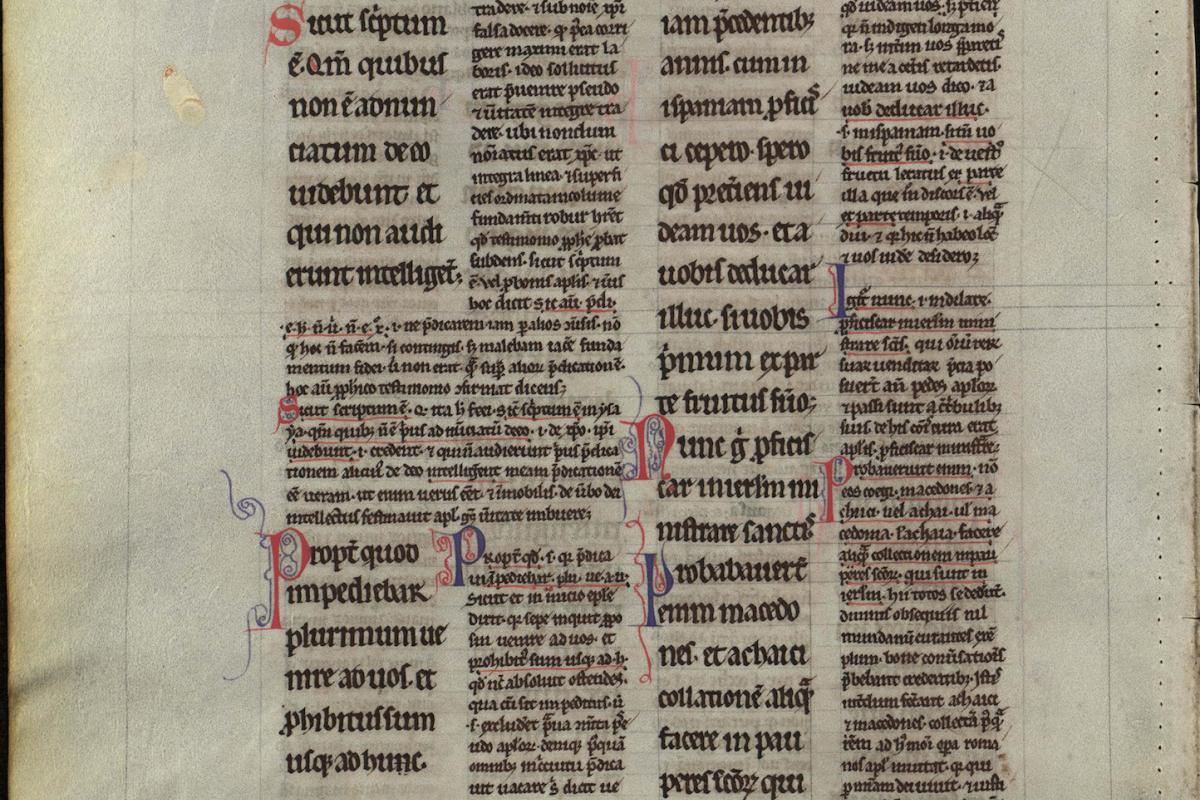

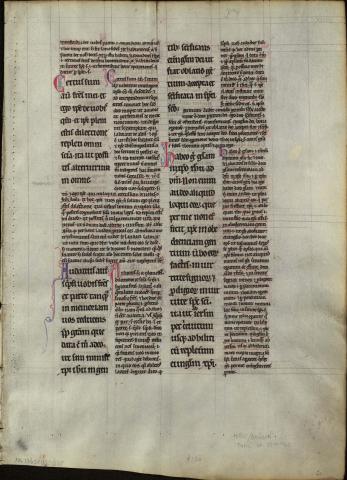

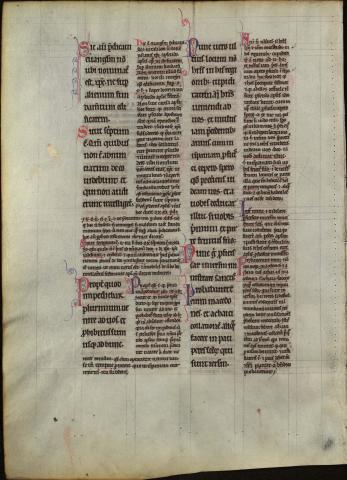

Single Leaf; parchment; Latin text. One leaf from a manuscript of Peter Lombard's Glossa in epistolas Pauli. Contains the text of Romans 15:14-26 with commentary. 1r: Last six lines of commentary on Romans 15:13 followed by Romans 15:14-19 with commentary in parallel columns. 1v: Romans 15:20-26 with commentary in parallel columns.

vellum

height 35 cm (height 24.2 cm)

width 25.4 cm ( width 15.7 cm)

Portland State University Library Special Collections

Mss. 8, Rose-Wright Manuscript Collection no. 22

Luke Wohlgemuth, Medieval Portland Capstone Student, 2016

The French Bible Leaf in the Special Collections at the Portland State University Library is a double-sided leaf and a part of a gloss on the Latin Vulgate Bible. The manuscript has been dated to ca.1215 and appears to be a copy of the Collectanea, or Magna glossatura written by Peter Lombard (ca. 1095-1160), bishop of Paris (1159-1160). Noted as an accomplished scholastic theologian, his other works include Libri Quatuor Sententiarum and his participation in the commentaries of the Glossa Ordinaria. His work on the Magna glossatura eventually came to be a part of the official Gloss on the Bible.[1] The Magna glossatura was likely written between 1139 and 1141, and became one of the most cited, copied, and studied glosses of the 12th century.[2]

Glosses on the Bible have a long tradition even dating back to the 4th and 5th centuries by theologians such as Augustine of Hippo.[3] The term ‘Gloss’ comes from the Greek and Latin word meaning tongue or language, and past editors have noted that to read the Bible without these glosses meant to read a Bible which could not speak.[4] The composition of systematic glosses during the middle ages was developed at the schools of Laon and St.Victor of Paris, for research conducted by theologians as well as the teaching of students in biblical exegesis.[5] Commentators on the Bible, like Peter the Lombard, were involved not only with the growing theological ideas put forth by these glosses but on the evolution of the textual layout. This layout is described by Philipp Rosemann as “a shift of emphasis in the relationship between the Word of God and its human interpreters,” which gave glosses and their commentators greater status.[6] The layout of the text, present in this leaf as well as in the original Magna glossatura, is written in the intercisum (intercut) format, which was developed by Peter the Lombard.[7] It was developed as a way of distinguishing scripture from the commentaries by writing the biblical verses in a larger script and on alternate lines next to the commentary.[8] Scribes refined this layout by placing blocks of scripture on the left edge of the columns to balance the biblical verses with the commentary.[9] The intercisum began to be applied to glosses on all the books of the Bible from ca.1160 and on.[10] This method not only allowed Peter Lombard to perform commentaries concerning the traditional mode of reflection on the Christian faith, which regard the biblical text as sacra pagina, but also to provide commentaries on systematic theology.[11] Lombard writes on specific theological themes, such as the nature of the Trinity, and he also includes references to theology present in the works of other ecclesiastical figures and theologians such as Ambrose, Augustine, and Hugh of St. Victor.[12]

The copied gloss in this collection is made of parchment, which over time has begun to warp and discolor near the edges of the page. Pricking is visible on the outer left margin of the leaf, which would be hidden when bound, as well as on the bottom, from where ruled lines can be seen emanating for the ordering of text. Both blue and red initial letters are present at the beginning of the bible verses and commentaries. The text itself is written in Latin in gothic textura, a form of Gothic script, which is characterized by its interwoven letters. This hand developed after 1190 and continued in popularity throughout the 13th century.[13] The recto and verso of the glossed leaf feature the Pauline Epistles, specifically Romans 15:14-26, with six lines of commentary on Romans 15:13 on the recto. In this portion of scripture, we see Paul writing to the Christians in Romans discussing the glory of Christ Jesus, Paul’s ministry among the Gentiles, and his longed-for return from preaching the Gospel where none had heard of Christ. The scholastic community regarded the Epistles of Paul as a theological work, and Paul saw it as not only a source of Christian doctrine but an interpretation of it.[14] The sections of scripture use the intercism format, carried over from the original Magna glossatura. The presence of this format in a copied work shows that commentators, like Lombard, still possessed a high status.

It is likely that Cistercian monks copied glosses like this one, as they were very involved in the process. In addition, the vellum used in Bibles like this one required numerous sheep, which monasteries usually had in abundance.[15] By the second half of the 13th century, works like this one would have been rare.[16]

Notes

[1] Philipp W. Rosemann, Peter Lombard. Great Medieval Thinkers. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, (2004): 50.

[2] Marcia L. Colish, Peter Lombard. Brill's Studies in Intellectual History, v. 41/1-41/2. Leiden; New York: E.J. Brill, (1994): 156.

[3] Constance B. Bouchard, “The Cistercians and the ""glossa Ordinaria,”

The Catholic Historical Review 86 (2). Catholic University of America Press, (2000): 184.

[4] Lesley Smith, The Glossa Ordinaria: The Making of a Medieval Bible Commentary,

Commentaria (Leiden, Netherlands); v. 3. Leiden; Boston: Brill, (2009): 1

[5] Bouchard, “The Cistercians and the ""glossa Ordinaria,” 185-186.

[6] Rosemann, Peter Lombard: 53.

[7] Smith, The Glossa Ordinaria: 130-131.

[8] Rosemann, Peter Lombard: 52.

[9] Ibid., 52

[10] Ibid., 52

[11] Rosemann, Peter Lombard: 45.

[12] Ibid., 45

[13] Juan-Jose Marcos Garcia, Fonts For Latin Paleography, Plasencia, Spain. (2014): 55-56.

[14] Colish, Peter Lombard: 192.

[15] Bouchard, “The Cistercians and the “Glossa Ordinaria,” 187-189.

[16] Ibid., 186.

Bibliography

Bouchard, Constance B., 2000. “The Cistercians and the ‘Glossa Ordinaria’.

The Catholic Historical Review 86 (2). Catholic University of America Press: 183–92. http://www.jstor.org.proxy.lib.pdx.edu/stable/25025708.

Colish, Marcia L. Peter Lombard. Brill's Studies in Intellectual History, v. 41/1-41/2. Leiden; New York: E.J. Brill, 1994.

Juan-Jose Marcos Garcia, Fonts For Latin Paleography, Plasencia, Spain. (2014). PDF user's

manual. http://guindo.pntic.mec.es/jmag0042/LATIN_PALEOGRAPHY.pdf

Rosemann, Philipp W. Peter Lombard. Great Medieval Thinkers. Oxford; New York: Oxford

University Press, 2004.

Smith, Lesley. The Glossa Ordinaria: The Making of a Medieval Bible Commentary.

Commentaria (Leiden, Netherlands) ; v. 3. Leiden ; Boston: Brill, 2009.

Links

https://exhibits.stanford.edu/mss/catalog/vn453zz8352