Commentary on the Sentences of Peter Lombard | Commentaria in aliquas distinctiones Sententiarum

Commentary on the Sentences of Peter Lombard (Commentaria in aliquas distinctiones Sententiarum)

German, 13th century

Language: Latin

vellum

height 24 cm

width 17 cm

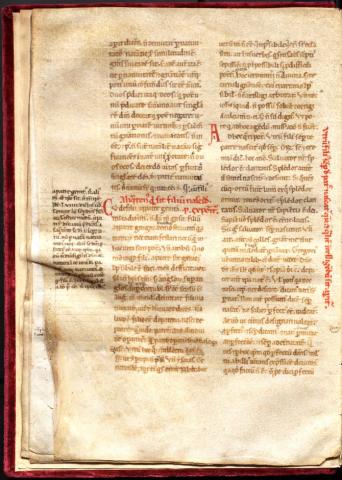

Text written in miniscule in two columns ruled by slight etches into the vellum. Prickings remain intact in the margin. The author of these commentaries of Peter Lombard’s Sentences is unknown, and this codex seems to be an extract from a larger work. Many passages are erased and replaced in their correct form by a modern hand. Extensive marginal notations on f. 10v. Chapter headings are missing after f. 47v. Second hand begins on f. 47v. and appears responsible for earlier textual corrections. Occasional insignificant stains.

University of Portland, Clark Library, Ms VI B

Jacob Sherman - Medieval Portland Capstone Student, 2008

Incipit: Si qualiter naturali rationis ducatur deum unum meus humana repperit. Summus [?] omnium principes ... eminentia diuinitatis iusitati eloquum facultatem Vrius siquid Verius siquid cogitatur deus quam dicitur uerius est qui cognetur tria quippe sunt. Res ipsum in effabiliter intellectus. Sed non res intellectus ostende...

In the University of Portland’s Special Collections sits a well-preserved thirteenth or fourteenth-century commentary on Peter Lombard’s Sententiae in quatuor IV libris distinctae or Sentences Divided into Four Books. In his book on the great medieval thinker and Bishop of Paris, Phillip Roseman writes that, “For several centuries, these Sentences [...] served as the standard theological textbook in the Christian West” (3). With that in mind, this unpublished commentary is of critical importance and must continue to be preserved because it provides a unique glimpse of a seminal moment in the doctrinal history of the Roman Catholic Church.

Written on fifty-five vellum folios, this commentary has a modern binding of crimson velvet; however, the binding remains extremely stiff, and at certain points the binding is completely exposed when the book is opened. The vellum is well-preserved, especially the latter folios which have experienced less oxidation, and the whole text only suffers from the occasional and insignificant stain. This commentary appears to be written by at least two scribes: the first composed ff. 1-47; the second scribe wrote ff. 47v.-55, while also making numerous textual corrections and notations. Other hands appear within the manuscript, but their writing does not affect the text; these hands exist only in the margins. The manuscript is written in black ink and the chapter headings are capitalized in red; however, with the second scribe, after f. 47v. the chapter headings and red ink disappear. The text is written in two columns in a minuscule hand, and appears to be Gothic Textura or Gothic Rotunda.[1] The commentary is lined by slight etches into the vellum and the manuscript’s marginal pricking remains clearly visible and almost entirely intact. Sister Wilma Fitzgerald has dated the manuscript to the fourteenth century, and she believes it comes from Germany. There is also a watermark of a man placing a tray in a large vat, which is located in the manuscript’s end papers.

In the introduction to his translation of Peter Lombard’s Sentences, Giulio Silano states that, “Despite the centrality of Peter Lombard’s work in the history of the Western academic tradition, very little is known about his life” (Vol. 1, ix). Silano supports the belief that Peter Lombard was probably born in Northern Italy near the end of the eleventh century. At some point Peter moved to Paris, a city which had become the Medieval leader in academics and what would eventually become theology. Silano continues, stating: But it is difficult to know what specific form Peter’s academic activity took since little is known about the structure of studies at this early stage of what would become the University of Paris, or of Peter’s role in such studies. But by 1144, a poet in far-off Barvaria could list him as one of the celebrated theological luminaries of the Parisian schools [p. xi]. Continuing his brief timeline of Lombard’s life, Silano points out how Lombard quickly moved up through the papal ranks, eventually becoming Bishop of Paris in 1159, only to die a year later on July 21 or 22, 1160. It is startling that so little is known about Peter Lombard’s life, especially after considering the centrality of Lombard’s work to the Medieval Roman Catholic Church.

This paper opened with a quote from Phillip Rosemann, to which I would like to return: “For several centuries, these Sentences Divided into Four Books served as the standard theological textbook in the Christian West. Only in the sixteenth century were they gradually replaced by Thomas Aquinas’s Summa theologiae” (3). But Rosemann is not alone in his praise; in fact, a more contemporary perspective derives from the famous poet Dante Alighieri, and in Paradiso, he places Peter Lombard in eternal heaven.[2] While these positions may feel extreme, they can hardly be understood without first gaining a general knowledge of Peter Lombard’s Sentences.

In essence, Lombard’s Sentences functioned as a collection of scriptural and theological quotations - or sententiae - which Lombard arranged in a systematic order, while synthesizing the passages and taking into account the theological issues of his day (Rosemann, 4). Written around the mid-1150s,[3] the Sentences are divided into four books and: Book 1 treats of God as Trinity; Book II is concerned with creation, the angels, the fall and grace; Book 3 addresses the reparation of fallen humankind by the Incarnation of the Word, as well as the virtues, vices and commandments; Book 4 presents the sacraments and the last things. Apart from this division into books, the Sentences, as it left Peter’s hand, appears only to have been subdivided into chapters and to have contained rubrics [Silano, xxvi]. Though the description addresses the Sentences as a physical text, it only hints at the important role these four books played in the Medieval church. Their reach was all-encompassing, as Phillip Rosemann states: The Sentences shaped the minds of generations of theologians during one of the most formative periods in the history of Christian doctrine. Indeed, since in the medieval university it was part of the duties of every aspiring master of theology to lecture on the Sentences, there is no piece of Christian literature that has been commented upon more frequently - except for Scripture itself [3].

The importance of the Sentences is articulated in the fact that all medieval theologians would have lectured on them, and thus hopefully known them intimately, but their importance feels all the more impressive when one learns that the Sentences were commented upon by the likes of Alexander of Hales, Bonaventure, Thomas Aquinas, Duns Scotus, and Martin Luther, just to name a few (Rosemann, 3).

Whether or not the University of Portland’s unpublished commentary was written by a famous theologian, I believe their manuscript is a commentary that focuses on Book II of Peter Lombard’s Sentences in Four Books. Between both Sister Wilma and myself, we have been able to relate three passages from this commentary to their specific distinctions in Book II of the Sentences. I will turn to those distinctions momentarily, but it must be noted that this Latin commentary does begin with the first distinction from Book II. Peter Lombard’s Liber Secundus begins:

DISTINCTO PRIMA.

UNUM ESSE RERUM PRINCIPIUM OSTENDIT; NON PLURA,

UT QUIDAM PUTAVERUNT.

1. Creationem rerum insinuane Scriptura, Deum esse creatorem initiumque temporis atque omnium visibilium vel invisibilium creaturarum in primordio sui ostendit, dicens, Gen.1 : In principio creavit Deus caelum et terram (Migne, p. 651 text, p. 333 pdf.)

The title of Lombard’s first distinction is unmistakable; its translation reads, “HE SHOWS THAT THERE IS ONLY ONE PRINCIPLE OF THINGS, AND NOT MANY, AS SOME HAVE HELD” (Silano, 3). This differs from what Sister Wilma has clearly identified as the first chapter heading in University of Portland’s Latin commentary, which reads in red ink, “Si qualiter naturali rationis ducatur deum unum meus humana repperit” (f. 1). To a modern mind, it is puzzling why the beginning of this unpublished commentary does not correlate with the beginning of Lombard’s Book II, and this inconsistency certainly proves as an avenue for further research.

Despite this initial dissimilarity, we have been able to locate four separate passages which correspond to four “distinctions” that Lombard presents in Book II of The Sentences. Sister Wilma found that f. 47v. relates to distinction forty-three, chapter one. She has provided the following transcription of the text:

De peccato in spiritum sanctum quod dicitur etiam peccatum ad mortem. Preterea est peccatum quedam de quo beatus ioannes in epistola sua loquitur dicens. Est peccatum ad mortem non pro eo dico ut quis oret [I Ioh. 5, 16] qui sane multiplicater intelligi. Et primo qud ut peccatum non ad mortem uenale .../... sepultus est autem cum tam sero factum esset sicut sese haberet verba euangelii.

A comparison between the first sentence of this transcription and Lombard’s Latin chapter heading shows[4] that the two texts are unified in topic, which also proves true for the other two passages that I have located.

My most important breakthrough occurred with folio twenty-seven. Here, through careful comparison with the Latin original, I discovered that f. 27 contained a passage that referenced The Sentences, Book II, Distinction XIV, Chapter I, and that f. 27v. had a passage that spoke to Chapter V and VI of the same Distinction. According to the Patrologia Latina, Distinction XIV, Chapter I opens with the title, “DE OPERE SECUNDÆ DIEI, IN QUA FACTUM EST FIRMAMENTUM,”[5] while the chapter heading in the top right corner of f. 27 reads an abbreviated version, “De opere secunde diei.” The title headings are not their only similarity; there clearly exist a number of shared words, most noticeably the beginning of a Biblical quotation from Genesis, “Fiat firmamentum in medio aquarium...” or “Let there be a firmament in the middle of the waters...” (Gen. 1:6). There are probably more similarities to be discovered between these passages, but, due to my lack of knowledge about Latin, I must move on to the other passages I located.

Folio 27v. contains numerous short passages, two of which correspond to the title headings from Distinction XIV. According to the Patrologia Latina, these passages correspond to Chapters V and VI, but chapter headings appear somewhat arbitrary in that Giulio Silano’s English translation of The Sentences situates these passages as Distinction XIV, Chapters VII and IX. Though I have highlighted a slight tension between the editorial choices of Silano and Migne, this tension is reconciled by there being no difference in meaning between their two texts.

In the Patrologia Latina, the heading for Chapter V reads, “De opere tertiæ diei, quando aquæ congregatæ sunt in unum locum,”[6] whereas the commentary again uses an abbreviated version, reading, “De opere tertie diei.” According to Silano, this chapter from Lombard’s work speaks about, “THE WORK OF THE THIRD DAY, WHEN THE WATERS WERE GATHERED IN ONE PLACE” (61). The commentary’s abbreviated headings continue with Chapter VI. The Patrologia Latina offers the heading, “De opere quartæ diei, quendo facia sunt luminaria,” while the commentary simply reads, “De opere quarte diei.” [7] Silano translates this heading as, “ON THE WORK OF THE FOURTH DAY, WHEN THE LIGHT-GIVING BODIES WERE MADE” (62). This single folio is a rich source for textual comparison, and, upon having a second opportunity to view folio 27, I believe there are other short passages that are the commentaries on Distinctions XII-XV, “or an account of the six days of creation as described in Genesis” (Silano, viii).

Despite my research, many of this manuscript’s secrets continue to remain hidden, and it will only show its beauty through additional research. A knowledge of paleography could help both date and situate the text within Germany, providing crucial information about the specific cultural moment from which this text came. Was it studied or penned in a monastery, or was it used to lecture in a university? Why does the manuscript not begin with the first distinction from Book II? Further research on this text is needed, because once this commentary becomes better understood—both in its textual meaning, cultural importance, and historical significance—the manuscript will suddenly blossom and imprint a striking impression on the minds of modern scholars, reaffirming the centrality of Peter Lombard in the medieval church.

Notes

[1] See Medieval Writing in “Works Cited” for examples of both scripts.

[2] Dante, Paradiso, 10.107-108.

[3] Silano, p. xiii.

[4] See p.784 or Pdf.384

[5] See p.680 or Pdf.347

[6] Ibid.

[7] See p.681 or Pdf.348

Bibliography

Bayley, Harold. A New Light on the Renaissance: Displayed in Contemporary Emblems. New York: Benjamin Blom, 1967.

Brown, Michelle P. Understanding Illuminated Manuscripts: A Guide to Technical Terms. Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 1994.

Hunter, Dard. Papermaking: The History and Technique of an Ancient Craft. New York: Dover Publications, 1978.

Lombard, Peter. The Sentences. Trans. Guilio Silano. 2 vols. Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Medieval Studies, 2007.

Lombardi, Petri. “Sententiarum: Libri Quatuor.” Patrologia Latina. Vol 192. Ed. Jacques Paul Migne. Paris, 1880. 25 June, 2008. 265- (pdf.) http://www.luc.edu/faculty/mhooker/google_books-bible_judaism_christiani...

Medieval Writing. 14 July, 2008. http://medievalwriting.50megs.com/writing.htm

The Franciscan Archive. 27 June, 2008. http://www.franciscan-archive.org/lombardus/

Rosemann, Phillip. Peter Lombard. New York: OUP, 2004.

Wilma Fitzgerald, PhD, SP - Quoted with permission from an unpublished study

Commentarium in libros sententiarum Petri Lombardi. Saec. XIV ex. Germany. FF 55, 240 x 165 (174 x 102) mm. Two columns. Chapters headings and initials in red. Chapter headings are missing after f. 43. Modern binding of red velvet. Water mark of man placing tray in a large vat. German script below?

Si qualiter naturali rationis ducatur deum unum meus humana repperit. Summus [?] omnium principes ... eminentia diuinitatis iusitati eloquum facultatem Vrius siquid Verius siquid cogitatur deus quam dicitur uerius est qui cognetur tria quippe sunt. Res ipsum in effabiliter intellectus. Sed non res intellectus ostende

f. 47v. [In Lib. II. dist. 43, cap. 1 De peccato in spiritum sanctum quod dicitur etiam peccatum ad mortem]. Preterea est peccatum quedam de quo beatus ioannes in epistola sua loquitur dicens. Est peccatum ad mortem non pro eo dico ut quis oret [I Ioh. 5, 16] qui sane multiplicater intelligi. Et primo qud ut peccatum non ad mortem uenale .../... sepultus est autem cum tam sero factum esset sicut sese haberet verba euangelii.