Compilation of the Works of Saint Augustine

Compilation of the Works of Saint Augustine

Italian, 11th-12th century

Language: Latin

vellum

height 25.5 cm

width 17.5 cm

University of Portland, Clark Library, Ms III B

Rachel Correll, Medieval Portland Capstone Student, 2008

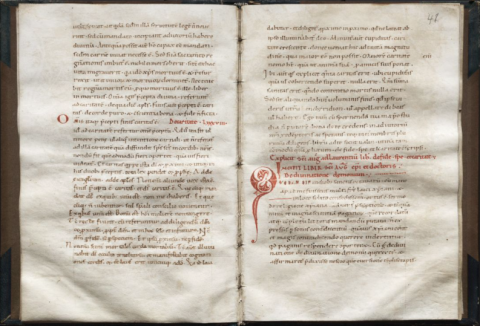

The University of Portland Library holds this compilation of works of St. Augustine (354-430), Bishop of Hippo, including some lesser-known ones. The first is the Enchiridion, followed by two treatises, De divinatione daemonum (On the Divination of Demons) and De vera religione (On True Religion), and two letters to Januarius, Epistolae duae ad Ianuarium. This is likely an Italian manuscript from the eleventh or twelfth century comprised of 95 folios and is 25.5 by 17.5 centimeters. The Latin texts are written in one column of 28 or 29 lines, in black ink, on vellum folios. The main text is written in uniform minuscule, while the chapter headings and initials are given in red ink and often finely ornamented. There are no illustrations included in this manuscript.

The current binding is modern, and some leaves are mutilated at the beginning and end. The modern binding is half morocco with gold-colored embellishment and an acorn pattern. The folios, however, are no longer attached to this newer cover. The uniform minuscule script is characteristic of the early medieval period, helping to place the date of this manuscript in the eleventh or twelfth century.

The pricking marks are still visible on many of the leaves' margins, as well as most of the rulings, both horizontal and vertical. At the time of the estimated construction of this manuscript, gray or reddish-brown plummet (or lead point) ruling was used, rather than ink, which comes into use later in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries.[1] These pricking marks and rulings are evidence of how the leaves were prepared for the written text. Some partial text is still visible on the fore-edges of the leaves as if it was used as a cue for the scribe and was meant to be trimmed off when the leaves were bound together.[2] If the leaves had been trimmed, the pricking marks would also not be visible today.

There are some marginal notes within the manuscript, including the nota monograms on 11r, 12v and 95r. These monograms are symbols for the imperative nota, which means, "Take note." They are comprised of an N with elongated stems so that "the O would be written at the bottom of the left stem of the N . . . the top of the right stem would be crossed to make a T; and the A would be written at the bottom of the right stem."[3] There are other examples of this nota bene mark on 7v. and 8r., but they are completely written out as nota rather than condensed into the monogram. 11r also has evidence of pen trials (probationes pennae) where the scribe, or more likely another, has scribbled in the lower margin to make sure the pen was writing properly before proceeding.[4] Though marginal notes were not uncommon in all types of manuscripts, the pen trials may be evidence that this manuscript was not as valuable.

One of the worst damages done to the manuscript is the removal of portions of certain leaves. Folios 63, 67, 91, and 93 all have scraps cut out of them. Sometimes certain passages from manuscripts are cut out to "be reassembled in an album, often for educational purposes."[5] There are other holes in the pages as well, but these might be original such as on f. 27 and f. 95 (the last page). These holes could be defects in the skin of the animal or even the result of damage done to the animal's skin in the process of making it into vellum.[6] On f. 27 the text appears to be written around the hole, rather than cut off by it, evidence that it was indeed original. These types of holes were often left unrepaired, as is the case here.[7] Again, the manuscript was probably less valuable because care was not taken to use only vellum without holes in the original construction.

Each work of Augustine within the manuscript is opened with a rubricated initial along with a few lines in red. Often the beginnings of passages also have a red initial set off from the rest of the text in the left margin. On 38r there are a few lines in red, but it seems that the method of erasure was used, and then new text was added that spills over and down into the right margin. The red ink is used throughout the manuscript as a way of highlighting certain passages, whether they are part of the Augustine texts or introductions to each of the texts. On 42r, a red decorated initial of the letter "O" begins the second text in the manuscript, De divinatione daemonum. This initial is sometimes called a littera florissa as it is embellished with "delicate geometric and foliate motifs."[8] Decorated initials can be much richer in color, design, and embellishment than this one, suggesting that this is a simpler manuscript, perhaps for private use. Considering the smaller size of the manuscript along with the lack of illumination, it is very likely it was not meant for display, but for a private library.

The first work within this manuscript is Augustine’s Enchiridion (Latin for "handbook"). The first leaf of this text is missing, while there are more missing leaves from the end of the manuscript. This is a treatise on the grace of God that deals specifically with faith, hope, and love.[9] It was originally written at the request of Laurentius, who was a Christian layman, during the year 421 CE.[10] His request was for the "essential Christian teaching in the briefest possible form."[11] Augustine touches on each of the issues of faith, hope, and love, including among them discussions on the creation, God’s treatment of the damned, and the Lord’s Prayer.[12] This work is not as well known as Augustine’s Confessions or City of God, but it is a good representation of his "fully matured theological perspective."[13]

The next work, On the Divination of Demons, begins on f. 42. Augustine wrote this somewhere between 406 and 411.[14] Though this treatise addresses the concept of evil, it has been said that other works of Augustine, especially The City of God, address it more fully. [15] It is interesting, then, that this specific work was chosen to be included in this manuscript. The basis of the text is a continuation of a discussion Augustine had with a few lay brothers, and thus it is written toward that audience. There are frequent biblical references and fewer references of a more intellectual and secular nature, as the lay brothers would not have understood such references as easily.[16] The actual text compares the abilities of demons with the power of God and concludes that God’s power of prophecy is far greater than that of the demons, and that God constantly demonstrates fulfillment of His word.[17]

Of True Religion follows, beginning on f. 48. It actually starts with an excerpt of Augustine’s Retractiones, in which he commented on this treatise along with some of his other works and reiterates his original purpose for it. In this, Augustine himself states, "the book is written chiefly against the two natures of the Manichees."[18] He attempts to render their views invalid by combating them with the views of the Church through biblical references and reasoning. The work is dedicated to Romanianus and was originally sent with a short letter in 390.[19] This is one of the five works that were sent to Paulinus of Nola. Paulinus called this package the "Pentateuch against the Manichees" in Letter 25.[20] Many view this work as exemplary of Augustine’s great genius.[21] It is interesting then that this wonderful work follows a lesser-known treatise that was written much later.

The following two works, Letters 54 and 55, which are closely related to one another, begin on f. 83 and f. 87. They are written to Januarius in response to his questions about various practices of the church including when to fast and what to do during Lent. Each was written around 400, and the second is a continuation of the first, though it deals mainly with the celebration of Easter and the importance of the day chosen to celebrate the Lord’s Passion.[22] Chapters 14 to 21 of the second letter are missing from this manuscript.

Augustine's works have always had a certain amount of popularity since the day they were written. To choose these specific works to include in this manuscript is interesting, to say the least. Just as the original intention of many of his treatises and letters were in response for requested advice, perhaps these were compiled together for a patron interested in the same issues. Little can be known about the original patron of this manuscript, except that he (or she) desired it for personal use and likely specifically chose these works for their uniqueness. Or perhaps they addressed issues relevant to the patron’s culture. Overall, they each offer evidence of God’s power, as well as the expertise of Augustine.

An unusual mixture of the works of Augustine, MS III B at the University of Portland Library is a unique work of art from the eleventh or twelfth century. It is also an example of the vandalism exercised on great works of art to serve the purposes of another. Hopefully, more work will be done relating to the texts in this manuscript as well as its original intended purpose to better illuminate its origins.

Notes

[1] Clemens, Raymond and Timothy Graham, Introduction to Manuscript Studies (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2007), 16, 17.

[2] Clemens, 21.

[3] Clemens, 44.

[4] Clemens, 45.

[5] Clemens, 114.

[6] Clemens, 13.

[7] Clemens, 13.

[8] Brown, Michelle P, Understanding Illuminated Manuscripts: A Guide to Technical Terms (Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 1994), 81.

[9] Augustine, Aurelius, Augustine: Confessions and Enchiridion, vol. VII of The Library of Christian Classics, trans. Albert C. Outler (Philadelphia: The Westminster Press, 1955), 20.

[10] Augustine, Enchiridion, 20.

[11] Augustine, Enchiridion, 20.

[12] Augustine, Enchiridion, 20, 21.

[13] Augustine, Enchiridion, 20.

[14] Augustine, Aurelius, Saint Augustine: Treatises on Marriages and Other Subjects, vol. 15 of The Fathers of the Church (Washington D.C.: The Catholic University of America Press, 1964), 417.

[15] Augustine, Treatises, 417.

[16] Augustine, Treatises, 418-420.

[17] Augustine, Treatises, 431.

[18] Augustine, Aurelius, Augustine: Earlier Writings, vol. VI of The Library of Christian Classics, trans. John H.S. Burleigh (London: SCM Press Ltd, 1953), 218.

[19] Augustine, Earlier Writings, 222.

[20] Augustine, Earlier Writings, 221.

[21] Augustine, Earlier Writings, 222.

[22] Augustine, Aurelius, Saint Augustine: Letters, Vol. I (1-82), vol. 12 of The Fathers of the Church (Washington D.C.: The Catholic University of America Press, 1964), 252, 260.

Bibliography

Augustine, Aurelius. Augustine: Earlier Writings. Vol. VI of The Library of Christian Classics. Translated by H.S. Burleigh. London: SCM Press Ltd, 1953.

--. Saint Augustine: Letters, Vol. I (1-82). Vol. 12 of The Fathers of the Church. Washington D.C.: The Catholic University of America Press, 1964.

--. Saint Augustine: Treatises on Marriage and Other Subjects. Vol.15 of The Fathers of the Church. Washington D.C.: The Catholic University of America Press, 1955.

--. Augustine: Confessions and Enchiridion. Trans. Albert C. Outler. Vol. VII of The Library of Christian Classics. Philadelphia: The Westminster Press, 1955.

Brown, Michelle P. Understanding Illuminated Manuscripts: A Guide to Technical Terms. Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 1994.

Clemens, Raymond and Timothy Graham. Introduction to Manuscript Studies. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2007.

Dr. Wilma Fitzgerald, SP - Quoted with permission from an unpublished study

Aurelius Augustinus, 1) Enchiridion ad Laurentium sive de fide, spe, et charitate liber unus, 2) De divinatione daemonum, 3) De vera religione, 4) Epistolae duae ad Ianuarium. Saec. XI/XII. Italy. FF 95, 250 x 170 (172 x 97) mm., one column, 28 /29 lines. Text mutilated at beginning and end. There are a number of marginal notes. Several scraps have been cut out on folios 63, 67, 91 and 93. Modern binding of Half morocco with gilt back although leaves are now free of binding. On folio 1: Iste liber est sancti sepulcri pluit [?] Unidentified sales catalogue # 11.

1) f. 2. Enchiridion ad Laurentium sive de fide, spe, et charitate liber unus. // [Sapientia verae donum exoptat Laurentio. Dici non potest dilectissime fili Laurenti ... (cap. iv) Haec autem omnia quae requires procul ... haec sunt defenden] da ratione que uel a sensibus .../...credens in adiutorio nostri redemptoris ac sperans teque in eius membris plurimum diligens librum ad te sicut ualui utinam tam commodum quam prolixum de fide spe et karitate [caritate] conscripsi. See PL 40. 231 (233A)-290

2) f. 42. De diuinatione demonium liber unum. Quodam die in diebus sanctis octauarum cum mane apud me fuissent multi fratres laici christiani et in loco solito .../... Iusticia autem mea in aeternum manet [Is. 51, 7-8]. Legant tamen haec nostra si dignantur cum ad nos contradicciones eorum peruenerint quantum dominus adiuuat respondebimus. Amen. See PL 40. 581-592; CSEL 41

3) f. 48. Retractationes libri II cap. xii de vera religione et De uera religione ad Romanianum. [Prologus Retractationes cap. xii] Nunc [Tunc] etiam de uera religione librum scripsi in quo multipliciter et copiosissime .../... Quod uerbum compositum est a legendo id est eligendo ut ita latinum uideatur religio sicut eligo. Explicit prologus. De uera religione. Cum omnis uitae bonae ac beatae uia uera in uera religione sit constituta in qua unus deus colitur et purgatissima .../... Per quem reformati sapienter uiuimus quem diligentes et quo fruentes beate uiuimus Unum deum ex quo omnia per quem omnia in quo omnia. Ipsi gloria in saecula seculorum amen. See PL 34. 121-171 and CSEL 36 {Retractationes libri II cap. xii]

4) f. 83v. Epistola ad Ianuarium presbyterum de diversis questionibus sive Ad inquisitiones Ianuarii. Dilectissimo filio Ianuario. Augustinus in domino salutem. Ad ea que me interrogasti mallem prius nosse quid interrogatus ipse responderes .../... His ut potui disputatis moneo ut ea que prelocutus sum serues quantum potes ut decet aeclesiae prudentem ac pacificum filium alia autem quae interrogasti si dominus uoluerit alio tempore expediam. Edited in CSEL 34.2, Epistola 54 page 158-168

5) f. 87. Epistola ad Ianuarium de ratione paschali sive Ad inquisitones Ianuarii liber secundus. Dilectissimo filio Ianuario Augustinus lectis litteris tuis ubi me commonuisti ut debitum redderem de residuis enodandis questionibus .../... baptismum in morte [Rom. 6, 3-4] unde nisi fide? neque enim iam in nobis perfectum est adhuc nobis metipsis ingemescentibus et adoptionem [ expectantibus redemptione corporis nostri spe enim salui facti sumus [Rom. 8, 24-25] ... hanc epistulam multis daturam atque lecturam] // Edited in CSEL 34.2 Epistola 55. pages 169-(198 line 6) 213