Homilies Leaf

Homilies Leaf

Italian, 12th century

Author: Bede the Venerable, Saint (Anglo-Saxon theologian and historian, 672/673-735)

Language: Latin

Single leaf: I. 18 In purificatione sanctae Mariae

ink on vellum

height 41 cm

width 28 cm

Portland State University Library Special Collections

Mss. 14, Rose-Wright Manuscript Collection no. 6

Kate Steinberg, Medieval Portland Capstone Student, Winter 2005

This single leaf from a twelfth-century copy of the Venerable Bede's (673-735) Homilia raises questions about the circumstances of its production. How did an eighth-century Anglo-Saxon text come to be reproduced and circulated through twelfth-century Italy? Bede wrote his Homilies on the Gospels late in his life, in the 720's while in the monastic community in Jarrow, England, and while they may have been directed towards the brothers living at Jarrow, scholars remain tentative in assuming that they were actually read aloud during mass as they lack eucharistic reference.[1] Bede and his community used the Neapolitan liturgy.[2] This choice suggests a continued dialogue between the Anglo-Saxon monasteries and those in southern Italy, which created an atmosphere for the transmission of the text to Italy. This example reverses the usual direction of the flow of culture and intellect from Rome to Northumbria, to Northumbria to Rome.

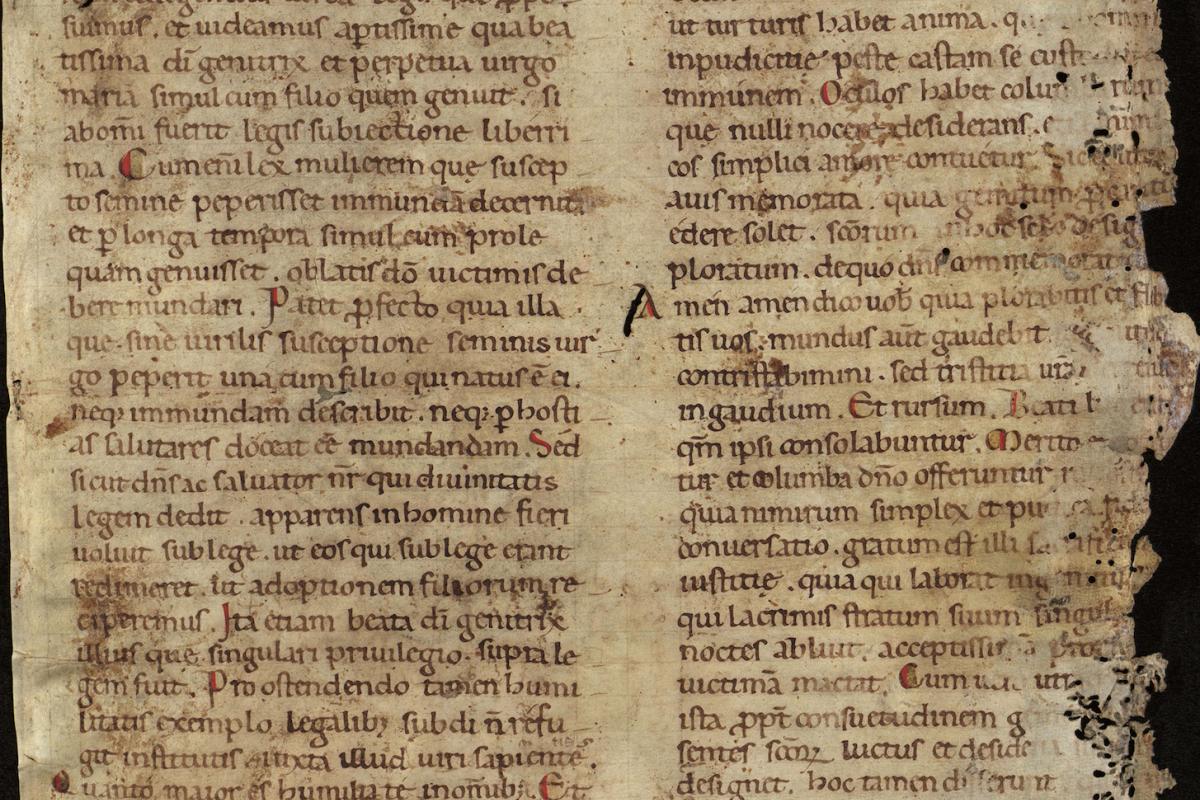

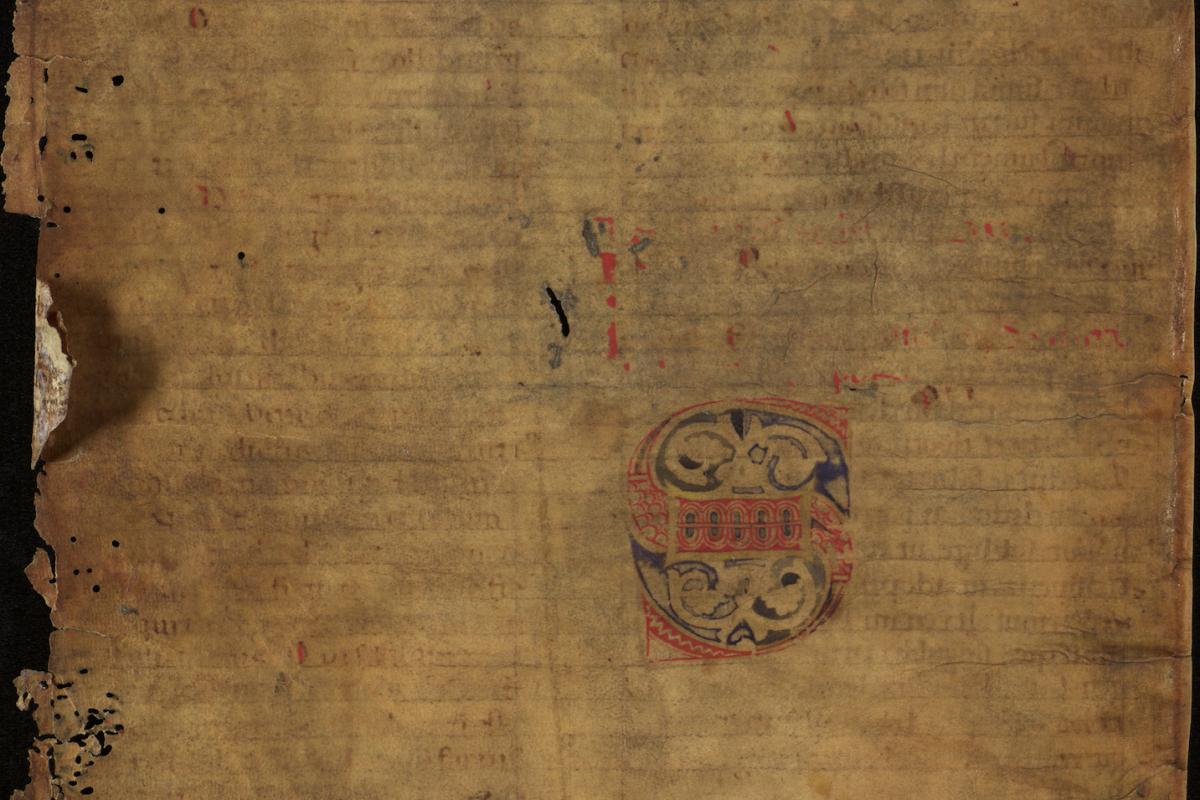

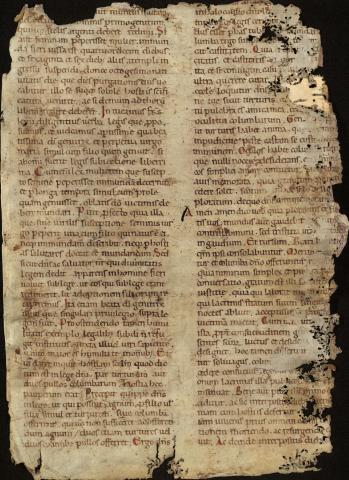

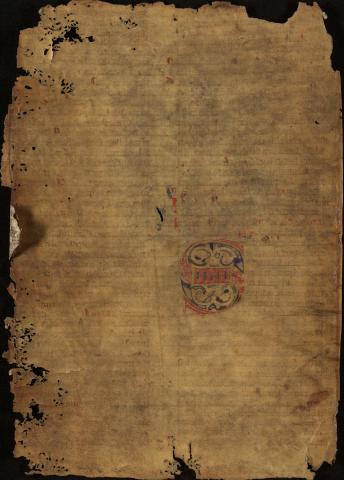

The page, made of vellum measuring 41 cm in length, is badly worn and shows signs of water damage. The recto, which in an intact manuscript would be on the right, has a large red and blue decorated initial S placed mid-way down the page. The incipit, as it was called, serves as the first letter of the first word in the homily, Sollemnitatem, and this was how the homily is titled within the manuscript. Nothing more exists on the page, signifying that the text has either been erased or was never finished. The verso, the back side or left in an intact manuscript, holds 44 lines arranged in two columns. The page itself suffered damage, possibly from fire and water, and shows wormholes along the edges, making it impossible to read the areas where the text has been completely eaten away. In the top right corner, it has been repaired with vellum patched onto the recto over the writing. The scribe left barely any margin and no decoration has been incorporated into the page, attesting to the supposition that this was made within a monastic community for functional use, using every bit of available material for this purpose. Red highlights appear in letters beginning new sentences and bleed through onto the recto; otherwise, the ink used was a dark earthy-brown. The miniscule script is legible and follows the rubric, which has not entirely been erased.

The S on the recto has been decorated in a way closely related to the tradition of insular manuscript illumination native to the British. The letters enclosed in a rectilinear area show four blue knots in the open space of the curves of the S, two in the top and two in the bottom. Red scales and zigzag designs decorate the body of the letter and in the center, a blue and red geometric pattern lies horizontally. Perhaps the scribe employed such decoration to denote the Anglo-Saxon origin of the work.

The subject matter of the homily provides an interesting look into the Anglo-Saxon conception of the purification of the Virgin. A feast day celebrated in the church on February 2, forty days after the virgin birth of Christ when Mary presents Christ in the temple along with a sacrificial offering. The scriptures proscribe a new mother to bring a lamb for the burnt offering, or if she is poor, two turtledoves or two pigeons.[3] Bede explains that "a pigeon indicates simplicity and a turtledove indicates chastity, for a pigeon is a lover of simplicity and a turtledove is a lover of chastity- so that if by chance one loses its mate it will not subsequently seek another."[4] Bede puts great emphasis on the analogy of the turtledove and the pigeon for purity and simplicity, equating such birds to saints mourning the death of Christ. Bede's homily also investigates Mary's perpetual virginity and states that she was above the law, but humbled herself and subjected herself to the established Mosaic Law. Mary's role is stressed over Christ's, as was often the case for this particular feast in western Europe, as opposed to the eastern church's emphasis on the coming of the Lord into the house of God for the first time.

Given the elusive history of the leaf, there are only a few things we can discern with certainty. First, the text comes from Bede's homily on the Feast of the Purification, and was likely to have come from a copy of Bede's Homilies on the Gospels, since they were conceived as a collection of about fifty in number. Second, the Italian copy of this text was most likely to have been produced within a monastic community as well. The lack of decoration, simple organization on the page, and clear script all suggest that it may have been used as a lectionary text. The language of this copy is in Latin and Bede himself wrote in Latin, which was still the official language of the church in twelfth-century Italy. Also taken into consideration can be the twelfth-century spiritual revival and monastic reform, which would have provided ample basis for the survival and coping of important earlier ecclesiastical works. Because Bede's work was a masterpiece of monastic literature,[5] one can easily understand how it would have continued to be used within monastic communities, even those outside the Anglo world, such as in this case, and especially if there had been established ties with the origins of the monastic communities in Northumbria.

Notes

[1] For the dating of the Homilies, see W.F. Bolton, A History of Anglo-Latin Literature 597-1066 (Princeton, 1967) 167. In his Introduction Lawrence T. Martin cautions the original intent of the Homilies, see his book Bede the Venerable Homilies on the Gospels, (Kalamazoo, 1991) xi. Bede's letters provide insight in the testaments of his fellow brothers who had traveled to Rome in order to bring back knowledge of the Roman liturgy and other such needs the initial monastic communities sought. For a contextualized history of Bede's contemporaries who traveled to Rome see, Eamonn O Carragain, The City of Rome and the World of Bede, Jarrow Lecture, 1994. (J & P. Bealls: Newcastle upon Tyne).

[2] Bolton, 166.

[3] Leviticus 12:6-8; Luke 2:22-35

[4] Translation in Martin, 181.

[5] Bolton, 167.

Transcription by Kate Steinberg, Medieval Portland Capstone Student, Winter 2005

Text in translation:

The Venerable Bede, Homily I. 18, Feast of the Purification, Luke 2:22-35

Translated by Lawrence T. Martin and David Hurst OSB. Bede the Venerable: Homilies on the Gospels. Book One. Advent to Lent. Cistercian Studies Series: Number one hundred ten. Kalamazoo: Cistercian Publications, 1991 (179-186).

The sacred reading of the gospel tells us about the solemnity we celebrate today. We venerate it with proper offices on the fortieth day after the Lord's birth. It is dedicated especially to the humility of our Lord and Savior, along with that of his inviolate mother. [The reading] explains that they who owed nothing to the law made themselves subject to the fulfillment of its legal decrees in everything. For, as we have just heard when [the lesson] was read, After the days of his or her[1] (either the Lord's or his mother's) purification were fulfilled according to the law of Moses, they took him to Jerusalem to present him to the Lord, as is written in the law of the Lord: every male that opens the womb shall be called holy to the Lord.

Now the law commanded that a woman who had received seed[2] and given birth to a son was unclean for seven days, and on the eight day she was to circumcise the infant and present him with a name. And then for another thirty-three days she was to abstain from entry into the temple[3] and from her husband's bed, until, on the fortieth day after the birth, she was to bring her son with sacrificial offerings to the temple of the Lord. The firstborn of all of the male sex was to be called holy to the Lord, and for that reason all clean [beasts] were to be offered to God; unclean ones were to be exchanged for clean ones, or killed, and the firstborn of a human being was to be redeemed[4] for five pieces of silver.[5] If, however, a woman gave birth to a female, she was ordered to be [judged] unclean for fourteen days, and to be suspended from entry into the temple for sixty-six more days,[6] until the eightieth day after the birth, which was called the day of her purification. On this [day] she was to come to sanctify herself and her child by sacrificial offerings, and thus at last she would be free to return to her husband's bed.

Dearly-beloved brothers, let us look more carefully at the words of the law which we have set before you, and we will see most clearly how Mary, God's blessed mother and a perpetual virgin, was, along with the Son she bore, most free from all subjection to the law. Since the law says that a woman who "had received seed"[7] and given birth was to be judged unclean, and that after a long period she, along with the offspring she had borne, were to be cleansed by victims offered to God, it is evident that [the law] does not describe as unclean that woman who, without receiving man's seed, gave birth as a virgin, [nor does it so describe] the Son who was born to her; nor does it teach that she had to be cleansed by saying sacrificial offerings. But as our Lord and Savior, who in his divinity was the one who gave the law, when he appeared as a human being, willed to be under the law, so that he might redeem those who were under the law, so that we might receive adoption as sons[8]- so too his blessed mother, who by a singular privilege was above the law, nevertheless did not shun being made subject to the principles of the law for the sake of showing [us] an example of humility, according to that [saying] of the wise man, The greater you are, the more [you should] humble yourself in all things.[9]

And let them give a sacrificial offering according to what is written in the law of the Lord, a pair of turtledoves or two young pigeons. This was the sacrificial offering of poor people. The Lord commanded in the law that those who could were to offer a lamb for a son or a daughter, along with a turtledove or a pigeon, but one who did not have sufficient wealth to offer a lamb should offer two turtledoves or two young pigeons.[10] Therefore, the Lord, mindful in everything of our salvation, not only deigned for our sake to became a human being, though he was God, but he also deigned to become poor for us, though he was rich, so that by his poverty along with his humanity he might grant to us to become sharers in his riches and his divinity.[11]

But I would like to look briefly at why it was ordered that these birds in particular were to be offered as a sacrificial offering for the Lord. We read that long before the law the patriarch Abraham offered these [birds] in a holocaust for the Lord,[12] and in very many ceremonies of the law one who needed to be cleansed was ordered to be cleansed by [offering] these [birds].[13] A pigeon indicates simplicity, and a turtledove indicates chastity, for a pigeon is a lover of simplicity and a turtledove is a lover of chastity[14]- so that if by chance one loses its mate it will not subsequently seek another.[15] Hence the Lord says in praise of the Church, Beautiful are your cheeks like a turtledove's.[16] And again, Behold, you are beautiful, my friend, behold, you are beautiful, your eyes are [like those] of pigeons.[17] A soul which has guarded itself, so as to be chaste and exempt from every infecting source of unchastity, has cheeks like those of a turtledove. [And a soul] which, desiring to harm no one, gazes even on its enemies with simple love, has eyes [like those] of pigeons.

Both of the birds mentioned, because they are wont to bring forth a moaning sound in place of a song, indicate the lamentation of the saints in this world,[18] which the Lord speaks of when he says, "Amen, amen, I say to you: you will wail and weep, but this world will rejoice; you will be sorrowful, but your sorrow will be turned into joy."[19] And again, "Blessed are those who mourn, for they will be consoled."[20] Therefore rightly are a turtledove and a pigeon offered to the Lord as a sacrificial offering, for the simple and modest way of life of the faithful is to him a pleasing sacrifice of justice, and one who labors in his grief and cleanses his couch with tears every night[21] slays a sacrificial victim most acceptable to God. Although because of their inclination toward grieving, both of these birds designate the saints' mourning in this present life and their heavenly desires, they nevertheless differ in this way, that the turtledove is inclined to grieve as it wanders by itself, but the pigeon in a flock. On that account, the first suggests the secret tears of [private] prayers, [while] the other suggests the Church's public gatherings.

It is good that the boy Jesus was first circumcised, and then after some intervening days he was brought to Jerusalem with a sacrificial offering. When still a young man, he first trampled all the corruption of the flesh under his feet by dying and rising, and then, after some intervening days, he ascended to the joys of the heavenly city, with the very flesh, now immortal, which he had made a sacrificial offering to God for our salvation. Each one of us is also first purged by the water of baptism from all sins, as if by a true circumcision, and thus advancing by the grace of a singular light to the holy altar, we go in to be consecrated by the saving sacrificial offering of the Lord's body and blood. Now also since the humanity of our Savior is uniquely simple and chaste, and since it is offered to the Father for us, it can fittingly be represented figurally by the immolation of a pigeon or a dove. But the entire Church too will, at the end of the world, first put off all blemish of earthly mortality and corruption in the general resurrection, and then be transferred to the kingdom of the heavenly Jerusalem, there to be commended to the Lord by the sacrificial victims, [her] good works.

Simeon and Anna, a man and a woman of advanced age, greeted the Lord with the devoted services of their professions of faith. As they saw him, he was small in body, but they understood him to be great in his divinity. Figuratively speaking, this denotes the synagogue, the Jewish people, who, wearied by long awaiting his incarnation, were ready with both their arms (their pious actions), and their voices (their unfeigned faith), to exalt and magnify him as soon as he came, acclaiming him and saying, Direct me in your truth and teach me, for you are my saving God, and for you I have awaited all the day.[22] This [interpretation] too must be mentioned, that deservedly both sexes hurried to meet him, offering congratulations, since he appeared as the Redeemer of both.[23]

It is surely with great foreboding, my brothers, that we should listen to the words which this same Simeon, prophesying about the Lord, spoke to his mother, "Behold, this [child] is destined for the ruin and for the resurrection of many in Israel, and for a sign that will be contradicted. And a sword will pierce your own soul, so that thoughts may be revealed from many hearts." It is with great yearning that we hear it said that he Lord is destined for the resurrection of many, for just as in Adam all die, so also in Christ all will be brought to life;[24] and he himself says, ""I am the resurrection and the life. Whoever believes in me, even if he dies, will live; and everyone who lives and believes in me will not die forever.""[25] But nonetheless, what is mentioned before [this] sounds frightening: Behold, this [child] is destined for the ruin... One who falls after having acknowledged the glory of the resurrection is unhappy enough, but worst is one who, having seen the light of truth, is blinded by the oppressive clouds of his sins. Hence we must take the utmost care always to remember to carry out in our works the virtuous good we have recognized, lest what the apostle Peter [said] might be said of us, that it was better for them not to have acknowledged the way of truth, than after the acknowledgement if it to have turned back from what was delivered over to them, that is, the holy commandment.[26]

"And for a sign," [Simeon] says, "which will be contradicted." Many of the Jews and many of the gentiles have often contradicted the sign of the Lord's cross externally, and, what is more serious, many false brothers [do so] internally. They follow it superficially in what they profess, but they trample upon it by the reality of their depraved actions, saying that they know God, but denying him in their deeds.[27]

"And a sword will pierce your own soul." [Simeon] uses the word 'sword' for the effect of the Lord's passion and death on the cross, and this sword will pierce Mary's soul, for she could not without painful sorrow see him crucified and dying. Although she was in no way uncertain about his rising in that he was God, nevertheless, in her fear she sorrowed that, as he was begotten from her flesh, he died.

"So that the thoughts of many hearts may be revealed." Before the Lord's incarnation the thoughts of many were concealed, and it was not fully evident who was on fire with the love of eternal things, [and] who in his mind preferred temporal things to heavenly goods. But when the King of heaven was born on earth, immediately every holy person rejoiced; Herod, however, was upset and all Jerusalem with him.[28] While [Jesus] was preaching and working miracles, all the crowds feared and glorified the God of Israel; the Pharisees and Scribes, however, with raging mouths criticized his saving words and deeds. When he suffered on the cross, the wicked were filled with foolish gladness, [and] the holy with righteous sorrow; when he rose from the dead and ascended into heaven, the gladness of the former was changed into everlasting joy.[29] And thus, in accordance with the prophecy of blessed Simeon, when the Lord appeared in the flesh, the thoughts of many hearts were revealed.

We must not believe that this revelation of the different thoughts took place only at that time in Judaea, and not also among us. Now too, with the appearance of the Lord, "the thoughts of many hearts are revealed" when the word of salvation is read or preached, and some hearers willingly give heed to it, rejoicing to accomplish in their actions what they have learned by hearing, [while] others turn away from what they hear, and do not exert themselves to do these things, but rather struggle against them, reviling them. Hence, brothers, whenever we perceive that the word of heavenly teaching is suffering some hostility from hardened hearers, we should imitate the sorrow of heart of those who, with sorrow befitting their compassion, sustained the Word of God when he suffered in the flesh. On the other hand, whenever we see that very same Word rise through love in the mind of his faithful hearers, and advance, through good works, to the glory of our Maker, we should rejoice with those who beheld Christ with blissful prayers when he rose from the dead and ascended to heaven.

Surely we recognize that it was the custom for birds to be offered to the Lord which were very chaste, simple, and made mourning sounds, and by these [birds] it is signified that the sobriety, simplicity and compunction of our heart must always be offered to our Creator. We should look more carefully at [the fact] that there was a reason why it was commanded that two turtledoves or two young pigeons should be offered, one of these for sin, and the other as a holocaust.[30] Now there are two kinds of compunction by which the faithful immolate themselves to the Lord on the altar of the heart, for undoubtedly, as we have received from the sayings of the fathers, the soul experiencing[31] God is first moved to compunction by fear, and afterwards by love. First it stirs itself to tears because when it recalls its bad [deeds and] becomes fearful that it will undergo eternal punishments for them- this is to offer one turtledove or a young pigeon for sin. When dread has been worn away by the long anxiety of sadness, a certain security is born concerning the anticipation of pardon, and the intellect is inflamed with the love of heavenly joys.[32] One who previously wept so that he would not be led to punishment presently starts to weep most bitterly because he is separated from the kingdom- this is to make a holocaust of the other turtledove or young pigeon.

A holocaust means something that is wholly burned up, and one makes oneself a holocaust to the Lord if, having rejected all earthly things, one takes a delight in burning with the desire of heavenly blessedness alone, and in seeking only this with lamentation and tears. His mind contemplates the choir of angels, the society of blessed spirits, [and] the majesty of the eternal vision of God, and he sorrows more because he lacks everlasting goods than he wept previously when he was apprehensive about eternal evils. [God] deigns to accept gladly both of the sacrificial offerings of our compunction, he who kindly pardons our mistakes because we have been chastised by mourning for our sins; and for the sake of [our] entry into eternal life he also restores by the light of his eternal vision those who are aflame with the whole concentration of their mind, Jesus Christ our Lord, who lives and reigns with the Father in the unity of the Holy Spirit for all ages. Amen.

[1]eius, which is ambiguous as to gender

[2] Lv 12:2

[3] Lv 12:1-4, 6

[4] Ex 13:2, 12-13

[5] Nb 18:15-16

[6] Lv 12:5

[7] Lv 12:2

[8] Ga 4:4-5

[9] Si 3:20

[10] Lv 12:6-8

[11] 2 Co 8:9; Ambr., Expos. evang. sec. Luc. 2,41 (CC 14: 49, 584/87)

[12] Gn 15:9

[13] Lv 1:14; 5:7; 11; 12:8

[14] Aug., Tract. in Ioh. 5 (CC 36: 46, 20/21)

[15] Jer,. Adv. Iov. 1, 30 (PL 23: 252)

[16] Sg 1:9

[17] Sg 1:14

[18] Aug., Tract. in Ioh. 6, 2 (CC 36: 53, 1 • 54, 31)

[19] Jn 16:20

[20] Mt 5:5

[21] Ps 6:6 (6:7)

[22] Ps 25:5 (24:5)

[23] Ambr., Expos. evang. sec. Luc. 2, 58 (CC 14: 56, 782)

[24] 1 Co 15:22

[25] Jn 11:25-26

[26] 2 P 2:21

[27] Tt 1:16

[28] Mt 2:3

[29] Jn 16:20

[30] Lv 12:8

[31] sentiens, var.: 'thristing for' (sitiens)

[32] Gerg., Hom. In Ezech. 10, 4-5, 20-21, (CC 142: 381, 95 • 383, 138; 395, 531/57); Moral. 32, 3, 4 (CC 143B: 1628, 23/33; 1629, 55/68)

Wilma Fitzgerald, PhD, SP - Quoted with permission from an unpublished study

Homiliarium. Beda Venerabilis, Homiliae in evangeliis I, 8. In purificatione sanctae Mariae. Saec. XII. Italy. One leaf 410 x 280(375 x 275) mm., two columns, 44 lines. Damaged at top and outer edge. Recto erased or badly worn, only the four-line red and blue initial: S for the beginning of the Homily: Sollemnitatem is legible. See: Beda Venerabilis Opera Pars III/IV. Corpus Christianorum Series Latina CXXII, Turnholt (Belgium) 1955, pages 128-130 line 83.

// S[olemnitatem nobis hodiernae celebritatis quam quadragesimo domincae natiuitatis die debitis ... ] autem mundis mutari uel occidi et hominis primogenitum quinque seclis [siclis] argenti debere redimi. Si autem feminam .../... ac sic interpositis diebus ierosolimam cum hostiis deferetur quia et ipse tam iuuenis prius omnem carnis corruptionem moriendo ac resurgendo calcauit Ac deinde interpositis diebus [cum ipsa carneiam inmortali quam pro nostra salute hostiam Deo facerat ad gaudia supernae ciuitatis ascendit] //