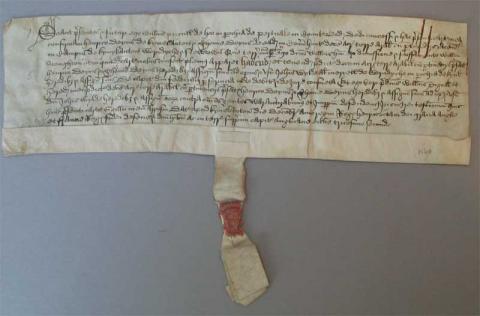

Land Conveyance with Partial Pendant Seal

Land Conveyance with Partial Pendant Seal Regarding Property in Kimbolton, Cambridgeshire, England

1540

Language: Latin

ink on vellum

height 18 cm | width 29 cm

Portland State University Library Special Collections, Mss 30

Rose-Wright Manuscript Collection no. 20

-----------

Dave Roletto, Medieval Portland Capstone Student Winter 2005

This document conveys the use of a 10-acre piece of farmland in England during the mid-sixteenth century (c. 1540). The parchment is 18 cm by 29 cm, and while the ink is rich and clear, it does contain one vertical fold and a stain from a paper clip in the upper right portion. The foot of the manuscript has a partial pendant seal. The left one-third and right one-third of the seal is missing. Latin is the language of the document and the layout of text comprises ten long lines. Every five lines has been numbered in modern hand in pencil at the left margin and the date has been written in a modern hand in pencil in lower right corner.

The document can be translated as follows:

William Pygull de Hoo of Perthale in Bedfordshire conveys 10 acres of farmland to Henry and Thomas Deym of Kimbolton, the land to be worked by John Wylde and Maryell [presumably his wife]. This document states that the property has been enfeoffed to Pygull by William Stoughton.

The parchment itself is made of vellum which is a writing surface, like paper. Vellum was made from animal skins, usually from cattle, sheep, goats, or antelope. The hair was scraped off of the skins, then they were washed, smoothed, and dressed with chalk. Vellum was used until the late Middle Ages when paper was introduced into Europe from China via Arab traders. Vellum lasted longer than papyrus and was tougher, but the edges sometimes became torn and tattered. Pendant seals were used when the transaction was agreed upon. They were made of hot wax and usually contained a heraldic mark. There is not enough left of this seal to know if it had such marks.

This document was written in secretary hand, which is an offshoot of the court hands of the beginning of the sixteenth century. The secretary hand crossed the Channel from Italy by way of France and was in use in England throughout the fifteenth century and later. The village of Kimbolton is mentioned in the document. Kimbolton is located in the county of Huntingdon. It is approximately 63 miles north/northwest of London. It is located on the edge of the county amidst sloping hills and woodland diversified with fertile valleys.

Background Essay: Land Use in Sixteenth-century England

During the price revolution of the period 1500-1640, in which agricultural prices rose by over 600 percent, the only way for landlords to protect their income was to introduce new forms of tenure and rent, and to invest in production for the market. Smaller landowners, such as the gentry and yeomanry, adopted these means earlier and on a wider scale than larger landowners, so that this group prospered relative to the aristocracy. The late-medieval pattern of tenancy and demesne usage in the manors of smaller landlords encouraged the early adoption of capitalist methods and the employment of wage labor. New capitalistic forms of management were created such as raised rents and entry fines. Although rents were slow to rise in the first half of the sixteenth century, after that time they increased at a rate that was far higher than the general level of prices. The rise of leaseholds also confirmed landlords' ultimate ownership of the land and tenants' strictly limited rights of temporary usage, which previously had been relatively undefined in customary possession. By the mid sixteenth century most demesne land had been leased or consolidated into landlords' hands and turned toward production for the market. The notion that whoever possessed and used property was as important as whoever owned it is one which is partially retained in modern generic definitions of the term 'property', for they include both possession and ownership.

Background Essay: Land Surveyors in England during Medieval Times

The principal task of the surveyor in the medieval economy was assessing and recording the customary obligations and rights of tenants of the manor, not the technical business of measuring the size of tracts or marking their boundaries as is the case with modern surveyors. He ""surveyed"" for his master in the sense of overseeing the broad scope of agricultural production on a manor. As such he kept the rolls and/or records of rights to land, of agricultural production, of the number of trees in the forests, and of the rents, fees, fines, or days of work due from each tenant to his lord. He presided at the court of survey where tenants were obliged under oath to report in detail their holdings, crops, livestock, and personal possessions.

Other important responsibilities were his care of the manor's boundaries, with which he was accompanied by his assistant, called a land-meter. Village elders showed the marks of old boundaries, while youths came along to learn them. His main obligation was to maintain traditional land boundaries. He was not authorized to alter or correct traditional lines, although the surveyor could add new markers where he found old ones when the old ones were damaged or gone. After he estimated the sizes of the various tracts, the surveyor was expected to value each parcel of arable, meadow, pasture, and woodland by classifying it as superior, mediocre, or inferior and by assigning a monetary value. The scope of the English surveyor's work in this period was legal, judicial, and mathematical, while requiring, as well, knowledge of all aspects of agricultural production.

Gradually during the course of the sixteenth century, the mathematical aspects of surveying assumed primary importance, although the other duties were not dropped. Only in the seventeenth century were the functions of land steward and land-meter distinguished firmly, and the modern conception of surveying as an occupation concerned with the location and measurement of plots of land finally established. The Renaissance influence in education and science, which coincided with changes in England's society and economy, provided the necessary intellectual foundation for the development of modern surveying.

Suggestions for further reading:

Books

Fryde, E.B., Peasants and Landlords in Later Medieval England. Stroud: Sutton, 1996.

Ison, Alf, A Secretary Hand ABC Book. Berkshire, UK: Berkshire FHS Books, 2000.

Martin, John, Feudalism to Capitalism: Peasant and Landlord in English Agrarian Development. Atlantic Highlands, N.J.: Humanities Press, 1983.

Websites

http://www.esh.ed.ac.uk/CEU/paper3.pdf

http://www.uk-genealogy.org.uk/england/Hunting donshire/towns/k/Kimbolton.html

http://www.english.cam.ac.uk/ceres/ehoc/datdescr.html