Legenda Aurea Sanctarum (The Golden Legend) Leaf

Legenda Aurea Sanctarum (The Golden Legend) Leaf

English (City of Westminster), 1527

Printed by William Caxton's assistant, Wynkyn de Worde

Single leaf with woodcut illustration and text from the Life of Saint Adrian

letterpress printing with woodcut illustration

ink on paper

height 26 cm

width 18 cm

Portland State University Library Special Collections

Mss 33, Gift in Memory of Louise A. Hunter

Regan Moore, Medieval Portland Capstone Student, 2005

Portland State University Special Collections Mss. 33 is an example of a woodcut print from England dating to 1527. The text tells "The lyfe of saynt Adryan" on both sides of the manuscript. The side that begins the saint's life also has a small figural drawing of Saint Adryan standing next to a small bird-like figure with a human head. The text is written in Old English. What is special about this manuscript page is its connection to William Caxton, who was the first to print books in English. Caxton likely translated this work from a popular French hagiographical text.

William Caxton (c. 1421-91) studied the printing process first in Cologne in 1471-72, then in Bruges in 1475. He traveled to England in 1476 and began working at Westminster until his death in 1491. His assistant, Wynkyn de Worde (d. 1535) took over Caxton's printing business after his death. Throughout the course of his printing career, Wynkyn de Worde issued some six hundred and forty books. Of these, about one hundred and fifty were religious treatises and service books.

Suggestions for Further Reading

- The Cambridge History of English and American Literature in 18 Volumes (1907-21). Volume II. The End of the Middle Ages. Section 15. Wynkyn de Worde.

- Plomer, H. Wynkyn de Worde and His Contemporaries: From the death of Caxton to 1535. Kent, 1974.

Rachel Correll, Medieval Portland Capstone Student, 2008

Among the special collections at Portland State University Library is Mss. 33, which is entitled in the catalog Leaf from The legende named in Latyn Legenda aurea that is to say in Englyshhe the Golden legend. In other words, this is one paper leaf from William Caxton's English translation (the Golden Legend) of the originally Latin Legenda aurea. In addressing the appearance, origin, and history of this leaf, this paper will focus on the physical description, William Caxton's translation, Golden Legend editions, Golden Legend as a text, the woodcut, and the typography.

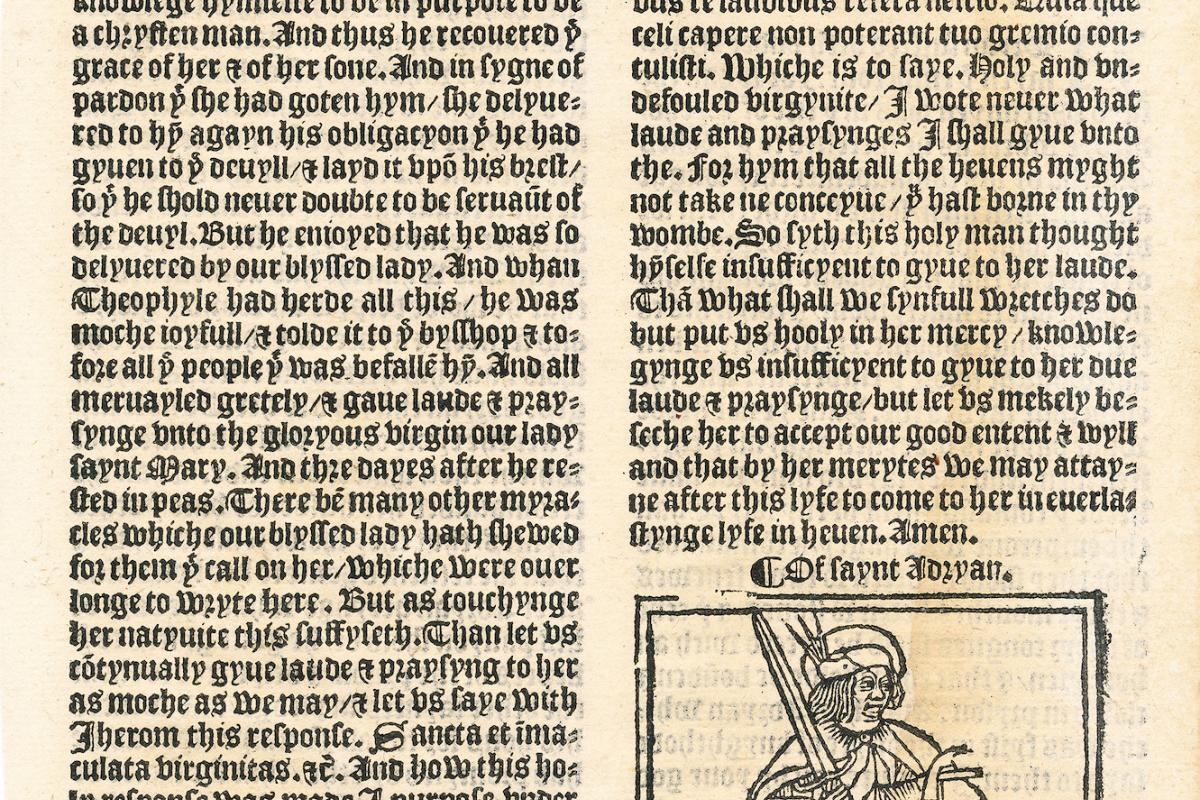

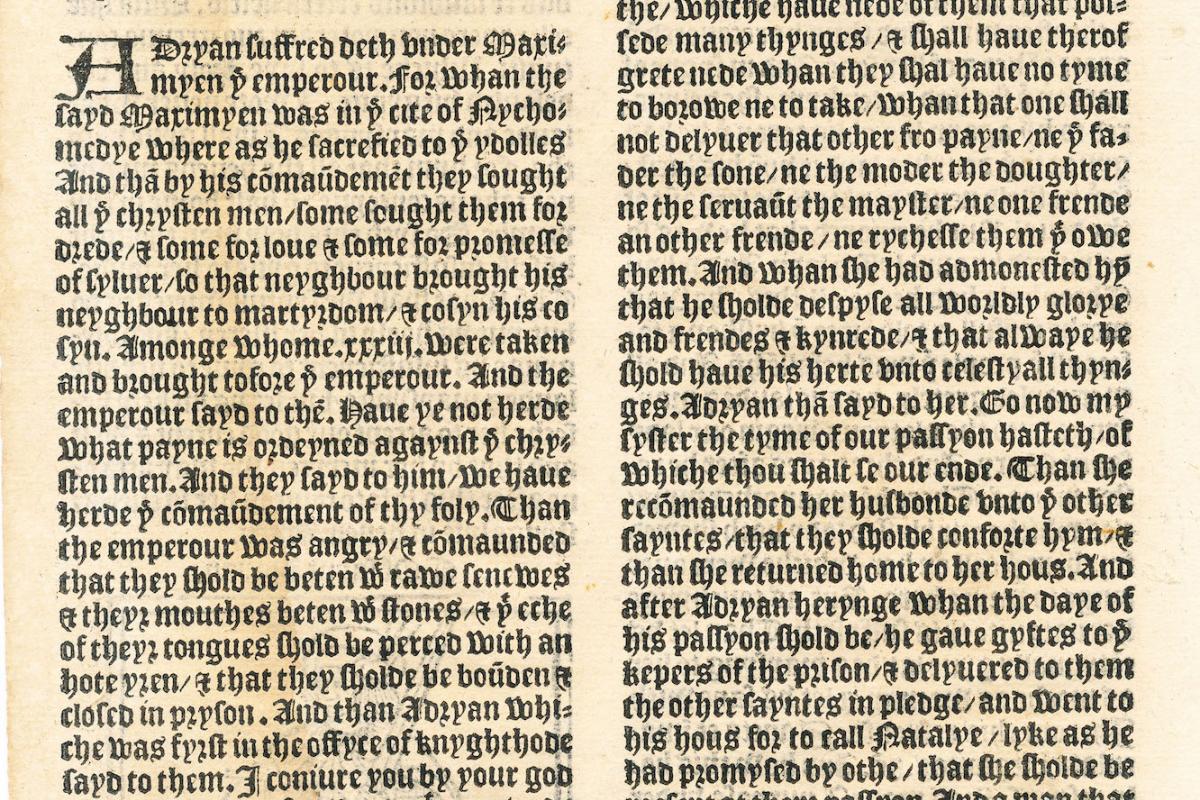

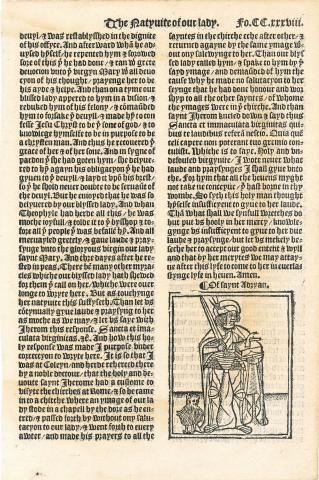

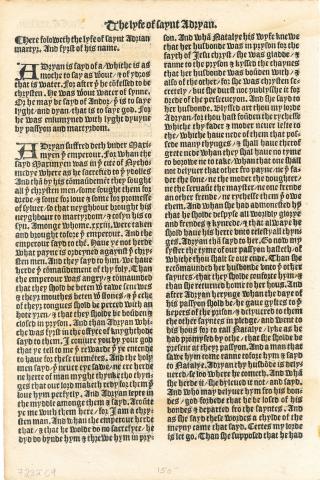

On the recto (f. 238r) is the last page of the story "The Natyuite of our lady" ("The Nativity of our Lady") with a woodcut in the bottom right corner that corresponds to the following story on the verso. Written there (f. 238v) is the first page of "The lyfe of saynt Adryan" ("The Life of St. Adrian"). The black ink text is printed in two columns of 47 lines each (except for the column with the woodcut which has 28 lines). The St. Adrian side has a large initial ""A"" printed twice at the beginning of the two paragraphs. The text is printed on paper, in which seven wire lines are still visible. These lines are created during the process of making the paper when the wet pulp is laid on wires to dry, a time when the paper is more delicate and susceptible to markings.[1] The paper is still in very good condition with all of its corners intact and no ripping along the sides. The only significant visible smudge is in the bottom left of the Our Lady page.

William Caxton (active 1476 to 1492) was an English translator, editor, merchant, and printer. He did not translate all of the works he printed, but he usually did print texts in the vernacular. He translated the Golden Legend from the original Latin by Jacobus de Varagene. However, he also used a French version, La Legende doree by Jehan de Vignay and an earlier English translation now known as the Gilte Legende.[2] This last translation is speculated to have been written by the Augustinian friar, Osbern Bokenham, though there is no clear evidence available.[3] Caxton likely also used a Latin text as well as a French translation when translating another of his works, The Game and Playe of the Chesse.[4] In Caxton's translation, he has a tendency to consult, and often combine, all three other versions before constructing his own. He also added stories about Old Testament figures and reorganized much of the text to include them.[5]

Caxton's choice to translate the Golden Legend seems to stem from his connection with Burgundian culture, which enjoyed books in the vernacular and contemporary popular English taste. Aside from Caxton personally spending 30 years near the Dukes of Burgundy, it seems that contemporary English culture also accepted Burgundian taste, making it easier for Caxton to be successful in printing as he was familiar with what the public wanted.[6] As N.F. Blake writes, "It is important for Caxton studies to realise that Caxton was acquainted with a major [Burgundian] library which contained mostly vernacular books and for which books were constantly being translated from Latin."[7] In fact, in the inventory from around 1467 for the Library of the Dukes of Burgundy, there were three copies of La Legende doree.[8] Furthermore, Caxton shows a trend of preferring to translate late medieval and continental religious works (the Legenda aurea was a late thirteenth-century work), while avoiding modern religious works that dealt with current issues.[9] When Caxton died in 1492 and Wynkyn de Worde took over his press until 1535, it was clear that de Worde's preference for which books to print was very different from that of his late master.[10] The fact that de Worde reprinted the Golden Legend demonstrates that it had a continued popularity into the early 1500s, which was unusual for books at this time to have such an extended demand.

It is thought that Caxton first acquired a printing press in Cologne on his trip there in 1471-72.[11] The printing press with movable type was first introduced in Cologne in 1464 after its initial production in the first half of the fifteenth century.[12] Thus, the development of the printing press had not advanced greatly, nor been introduced to England at the time of William Caxton's career. In fact, after Caxton had established his press in Westminster (around 1476), the only two known smaller presses were opened in Oxford and St. Albans, though each only lasted a couple years.[13] Caxton is really the beginning of book printing in England, and also a large figure in it, for his press prospered and lasted longer than contemporary presses throughout the country.

The Portland State University Library catalog states this edition of the Golden Legend is from 1527, which Wynkyn de Worde, William Caxton's assistant, printed. Caxton originally printed in Westminster a first edition in 1483 and some speculate a second edition was made in 1487, though no copies are extant.[14] Though cataloged as such, de Worde would probably not have been able to print his edition on the Westminster press as he moved his business to Fleet Street after 1500.[15] He also ran "an additional shop after 1509 at the sign of Our Lady of Piety in St Paul's Churchyard."[16] There are at least 30 copies of the first edition of the Golden Legend extant, giving evidence to the supposed popularity of the book. Of the works that Caxton translated and/or edited, there appears to be only one that has more copies that exist today, the Polychronicon.[17] The Caxton edition of the Golden Legend was likely funded by the patronage of William Earl of Arundel, whose name appears in both the prologue and epilogue.[18] The size of the original edition was unusually large, encouraging the idea that it was not meant for private use, but to be read from a lectern in a clerical setting.[19] The leaf is much smaller, more the regular size of printed books at the time, and is thus clearly not part of the original edition of the Golden Legend.

The full version of the Golden Legend is made up of stories, or sermons, that could have been read throughout the year.[20] Blake states that the work is divided into three parts: "(i) the episodes from the life of Christ; (ii) the early history of mankind; and (iii) the lives of the saints."[21] The leaf is clearly from the third section. Furthermore, there is a basic structure for most of the sermons on the lives of the saints, again divided into three sections: the etymology of his/her name, the story of his/her life, and the miracles he/she performed.[22]

The text of "The Nativity of Our Lady" on the leaf begins midsentence with "devyl & was restablysshed in the dignite of his offyce . . . " and ends with "and that by her merytes we may attayne after this lyfe to come to her in everlasstynge lyfe in heven. Amen." Although not perfectly following the format for the saints' lives stories, this one is similar in relating stories and miracles directly related to the Virgin, though few words are spent on the actual Immaculate Conception of the Virgin. It has been discovered that Caxton expanded on some of the stories from the earlier versions of the Golden Legend, though it is not yet clear how many. One, however, identified by Sister Mary Jeremy is the story of "The Nativity of our Lady."[23] This extra section starts at what was the original end of the story, and adds a personal story beginning with "Than let us continually gyve laude & praysyng to her as moche as we may . . ." This continues to the end of the page with the "Amen." All of this section is included in the leaf. The story he writes mentions his own trip to Cologne from July 17, 1471 to, at the latest, December 1472, where a story was related to him dealing with St. Jerome and the Virgin Mary.[24] Along with other features, this is clear evidence this is Caxton's own translation of the Golden Legend.

The Life of Saint Adrian begins with the etymology of his name, of which there are given two possibilities, and then begins the story of his life and martyrdom. The actual leaf does not reach the telling of his death and eventual miracles, but these are included in the full version of the Golden Legend. The text begins "There foloweth the lyfe of saynt Adrian martyr. And fyrst of his name." Interesting to note is that here de Worde chose to spell the saint's name "Adrian," like the modern spelling, while on the rest of the page it is spelled "Adryan." Though it was common when printing pages to abbreviate words or spell them completely out to accommodate the space on the page, this discrepancy does not serve that purpose. The text ends with St. Adrian's wife Natalye saying, "Certes my lorde is let go. Than she supposed that he had . . ."

Caxton began using woodcuts in 1481, and used English artists that often did not read the actual texts they were illustrating, but adapted them from other books and even manuscripts.[25] Between 1480 and 1535, there is record of 2,500 woodcuts in use in England.[26] The artist made woodcuts by taking a block of word and carving out the parts that were to be uncolored in the final image. The woodcut was then inked and pressed on the paper so an impression of the uncarved parts of the wood would appear on the page, creating an image. One woodcut could be used multiple times, simply by re-inking. Wynkyn de Worde had an interest in woodcuts and "his editions brimm[ed] with a total of more than 1,100 woodcuts."[27]

Caxton's edition(s) of the Golden Legend included woodcuts, like the de Worde edition from 1527. It is unclear if the same woodcuts were used between the Caxton and de Worde editions. The one printed on the de Worde leaf is vague enough with only two figures that it was likely used for multiple texts. Located on the side of Our Lady, it actually relates to the following story of St. Adrian. It is captioned "Of Saynt Adryan," with what appears to be a paragraph mark preceding the caption. The picture is of a man dressed in armor with a sword in his right hand and some sort of box(?) under his left arm. Accompanying him is a birdlike creature with a human face. Both figures stand in front of a horizon line, the only mark of a background in the image. No such creature is referenced in the actual text, again supporting the idea that this woodcut was used for the illustration of multiple books. It is somewhat appropriate for the figure to be dressed as a knight, as the story introduces Adryan as "fyrst in the offyce of knyghthode." However, the scene has little applicability to the actual text. In two German editions of the Golden Legend from 1481 and 1482 printed in The Illustrated Bartsch collection, the woodcuts for St. Adrian are much more applicable to his story. Each shows him in the process of being martyred, having his limbs chopped off by two figures, while other figures look on. These scenes are set in a still, simple background of barren hills, but are more complex than the blank background in the de Worde woodcut. Compared to these two woodcuts, it is clear that this one is an example of a generic woodcut being reused, and it was not created specifically for the story of St. Adrian.

The typography of this leaf appears to be an evolved form of Caxton's own type that was influenced by the Burgundian bastard script.[28] Bastard scripts are known for being a compromise between the Gothic court and book scripts.[29] The script was very useful for vernacular texts; hence it was appropriate for Caxton to base his own typefaces on it for his vernacular and translated texts. Assumedly, de Worde continued to base his own typefaces on Caxton's, thus the similarity between the typeface on the leaf and the typeface used in Caxton's The Dictes or Sayengis of the Philosophres from 1477.[30] This use of the bastard script proved useful for many at this time, including Emperor Maximilian in his Liber Horarum ad usum Maximiliani Imperatoris from about 1506-07, which was written in German.[31]

Other copies of the Golden Legend that survive today include an incomplete one in the Bodleian Library from the late fifteenth century and one from the Pierpont Morgan Library from the last quarter of the sixteenth century. The latter is actually a later copy of Caxton's text and is not directly from his press, and thus is not a word-for-word copy.[32] It is not clear what copy of the Golden Legend the Portland State leaf originated from, nor if that copy still exists today. However, this leaf is a wonderful example of the William Caxton translation of the Golden Legend, of the use of woodcuts in early English printing, of the Wynkyn de Worde edition of the text, and of printing in fifteenth- and sixteenth-century England.

Notes

[1]Greetham, D.C., Textual Scholarship: An Introduction (New York: Garland Publishing, 1992), 64.

[2] Blake, N.F., "William Caxton," Authors of the Middle Ages: English Writers of the Late Middle Ages, ed. M.C. Seymour, vol. III, no. 7 (Aldershot, UK: Variorum, 1996), 53.

[3] Jeremy, Mary, "The English Prose Translation of Legenda Aurea," Modern Language Notes 59, no. 3 (Mar. 1944): 182.

[4] Blake, N.F., "William Caxton: His Choice of Texts," Anglia 83, no. 3 (1965): 300.

[5] Blake, N.F., "The Biblical Additions in Caxton's 'Golden Legend,'" Traditio 25 (1969): 231-247.

[6] Blake, "His Choice of Texts," 294, 297.

[7] Blake, "His Choice of Texts," 297.

[8] Blades, William, The Life and Typography of William Caxton: England's First Printer (New York: Burt Franklin, 1861), 1:278.

[9] Blake, "His Choice of Texts," 291.

[10] Blake, N.F., William Caxton and English Literary Culture (Rio Grande, OH: The Hambledon Pres, 1991): 57.

[11] Blake, "William Caxton," 18.

[12] Blake, "William Caxton," 19.

[13] Blake, English Literary Culture, 57.

[14] Blake, "William Caxton," 53.

[15] Greetham, 107.

[16] Raven, James, The Business of Books: Booksellers and the English Book Trade 1450-1850 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007), 19.

[17] Blake, "William Caxton," 51-54.

[18] Blake, English Literary Culture, 105.

[19] Blake, English Literary Culture, 115.

[20] Blake, "Biblical Additions," 237.

[21] Blake, "Biblical Additions," 237.

[22] Blake, "Biblical Additions," 238.

[23] Jeremy, Mary, "Caxton's Original Additions to the Legenda Aurea," Modern Language Notes 64, no. 4 (Apr., 1949): 260.

[24] Blake, "William Caxton," 18.

[25] Blake, English Literary Culture, 26, 27.

[26] Raven, 16.

[27] Raven, 19.

[28] Greetham, 238.

[29] Greetham, 233.

[30] Greetham, 239.

[31] Morison, Stanley, Politics and Script: Aspects of authority and freedom in the development of Graeco-Latin script from the sixth century B.C. to the twentieth century A.D. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1972), 309.

[32] Blake, English Literary Culture, 296-297.

Bibliography

Blades, William. The Life and Typography of William Caxton: England's First Printer. Vol. 1. New York: Burt Franklin, 1861.

Blake, N.F. "The Biblical Additions in Caxton's 'Golden Legend." Traditio 25 (1969): 231-247.

---. William Caxton and English Literary Culture. Rio Grande, OH: The Hambledon Press, 1991.

---. "William Caxton." Authors of the Middle Ages: English Writers of the Late Middle Ages. Ed. M.C. Seymour. Vol. III, No. 7. Aldershot, UK: Variorum, 1996.

---. "William Caxton: His Choice of Texts." Anglia. 83, no. 3 (1965): 289-307. Greetham, D.C. Textual Scholarship: An Introduction. New York: Garland Publishing, 1992.

Jeremy, Mary. "Caxton's Original Additions to the Legenda Aurea." Modern Language Notes 64, no. 4 (Apr., 1949): 259-261. JSTOR. 19 June 200 http://www.jstor.org/stable/2909567.

---. "The English Prose Translation of Legenda Aurea." Modern Language Notes 59, no. 3 (Mar., 1944): 181-183. JSTOR. 19 June 2008 http://www.jstor.org/stable/2910879.

Morison, Stanley. Politics and Script: Aspects of authority and freedom in the development of Graeco-Latin script from the sixth century B.C. to the twentieth century A.D. New York: Oxford University Press, 1972.

Raven, James. The Business of Books: Booksellers and the English Book Trade 1450-1850. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007.

Suggestions for Further Reading:

- Blades, William. The Life and Typography of William Caxton: England's First Printer. Vol. 1 New York: Burt Franklin, 1861.

- Blake, N.F. William Caxton and English Literary Culture. Rio Grande, OH: The Hambledon Press, 1991.

STUDY GUIDE

Rachel Correll, Sophomore Inquiry Mentor Session, Winter 2012

The Text

This leaf is from a 1527 edition of William Caxton's translation into Middle English of the Golden Legend. The original religious work was written by Jacobus de Voragine in the thirteenth century. The full version of the Golden Legend is made up of stories, or sermons, that could have been read throughout the year. The work is divided into three parts: events from the life of Christ, the early history of mankind, and the lives of saints. The PSU leaf is from the third section. Furthermore, there is a basic structure for most of the sermons on the lives of the saints, again divided into three sections: the etymology or root of his/her name, the story of his/her life, and the miracles he/she performed. The portions of the two stories included on the PSU leaf are from the Nativity of Our Lady (the Virgin Mary) and the Life of St. Adrian.

The Printer and His Adaptation

William Caxton was active as a printer from 1476 to 1492 and was the first printer in England. Wykyn de Worde took over his business after his death and continued it until his own death in 1535. Caxton, in addition to being a printer, was also a translator, editor, and merchant. He chose to translate the thirteenth-century work Legenda aurea into the vernacular from Latin, basing his version not only on the original by Jacobus de Voragine, but also on at least one earlier English version and a French translation. As copyright did not yet exist, Caxton freely borrowed from the original and these other translations and even added his own stories to his new text of the Golden Legend.

The Editions

The first edition of the Golden Legend was printed by Caxton in 1483, of which at least thirty copies still exist today. The first printing was formatted for very large books that were likely meant to be read aloud, even used in sermons, rather than for private use. By the time de Worde made the ninth printing of the text in 1527 when the PSU leaf was printed, the Golden Legend had sufficient demand for it to be printed on paper appropriate in size for smaller books for private use. Just as Jacobus de Voragine's original Legenda Aurea was a bestseller in the Middle Ages, so Caxton's editions were greatly desired.

The Woodcuts

Between 1480 and 1535, there is a record of 2,500 woodcuts in use in England. There were at least 1,100 woodcuts in de Worde's edition of the Golden Legend, more than Caxton's original edition. It was typical at this time to reuse woodcuts throughout a text and even in other texts, and thus the images do not always correspond exactly with the text. As for the woodcut on the PSU leaf, it is meant to represent St. Adrian, as seen by its caption. It is of an armored man with a birdlike creature with a human face behind him, one that does not have any correlation with the text.

Inquiry

What specifically about the Legenda aurea do you think made Caxton want to translate and print it? Caxton's Golden Legend can be considered a collection of generous accounts and legends with a moralistic tone. Can you think of other books throughout history with similar themes? Make sure to examine the piece carefully. Do you notice the wire lines on the paper where it was laid on wires to dry? Look at the words. Can you read any of them? Now examine the woodcut. Why do you think it was chosen for the story of St. Adrian? Do you think it was an appropriate choice? Why or why not? Why do you think this text was so popular in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries? How does this leaf compare to a page from a book printed today?