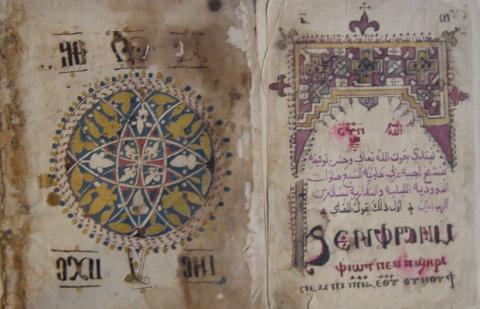

Prayer Book Leaves in Arabic and Coptic Script

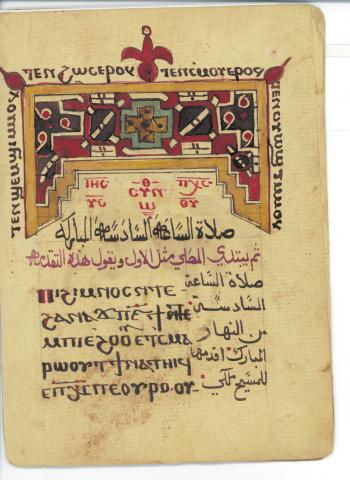

Prayer Book: Text

Podcast by Bronwyn Dorhofer

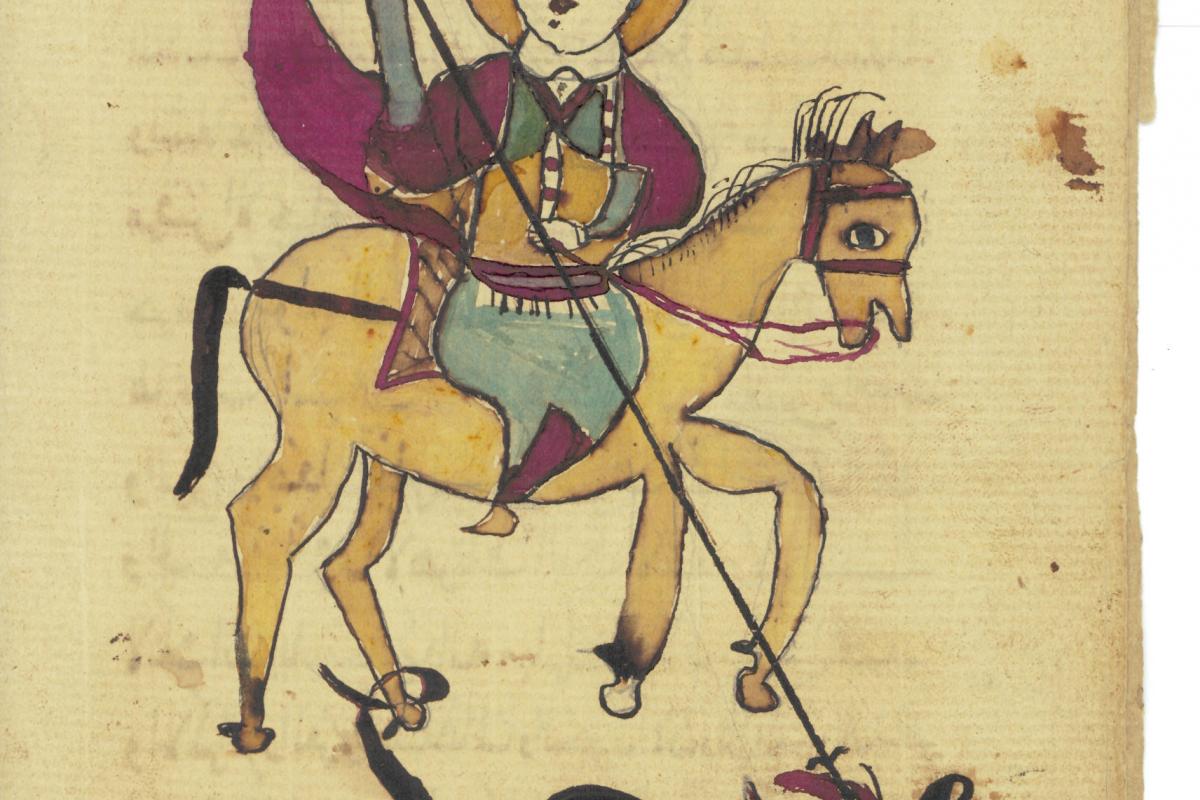

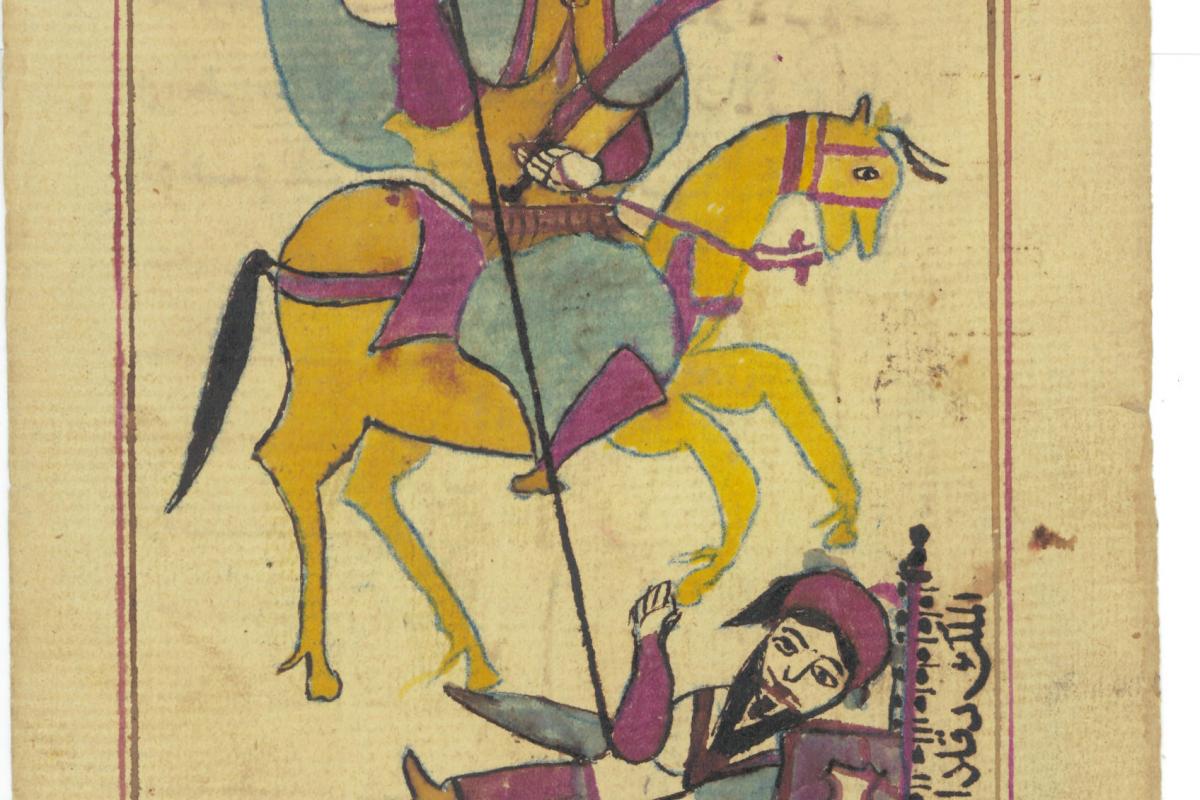

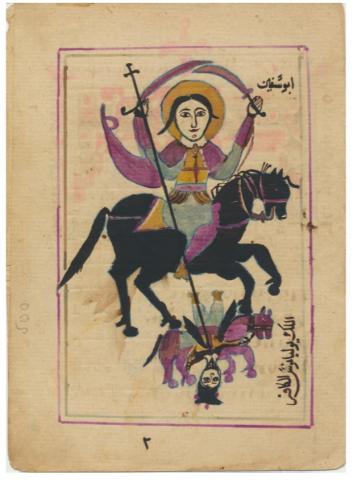

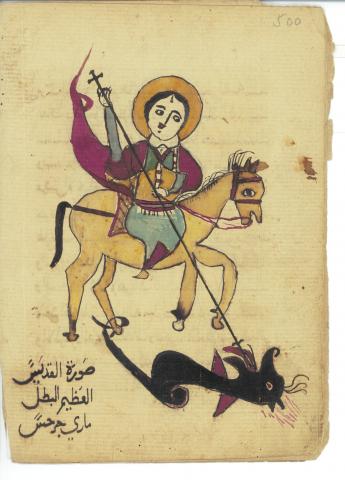

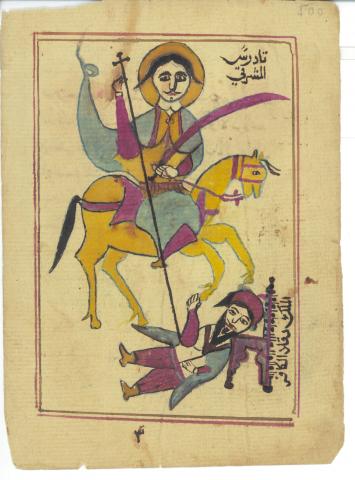

Prayer Book: Warrior Saint Images

Podcast by Denise Loncar

Prayer Book

Video by Jordan Long

Prayer Book Leaves in Arabic and Coptic Script

Coptic Egyptian, early 18th century

Language: Arabic

vellum

height 19.5 cm | width 13.7 cm

Portland State University Library Special Collections, Mss 40

----------

Bronwyn Dorhofer, Medieval Portland Capstone Student

Dating from the early eighteenth century CE, this hand-rendered manuscript fragment is an example of an Agpeya, or, a Coptic Book of Hours. Intended to be used as a daily prayer book, the manuscript contains twelve extant leaves painted on vellum pages and implements both bilingual liturgical text and ornamental iconography to emphasize the various stories told within its pages.[1] This particular manuscript contains the daily prayers associated with the Coptic cycle of canonical hours that relate to the various events in the life of Jesus Christ. The beginnings of the Third, Sixth, Ninth and Midnight Hours, as well as a protective nighttime prayer have all been identified with this text. Accompanying the hours are vivid illuminations such as ornamental chapter headings which clearly designate sections of the text, as well as compelling warrior saint imagery depicting Saint George, Saint Theodore and Saint Mercurius painted in a manner which aligns within Eastern iconographic tradition.[2] The twelve leaves contained within the Agpeya represent a limited but revealing example of the daily devotional life of a Coptic Christian and how the fragment may have been used and interpreted by its user.

Reading from left to right, the Agpeya features both Coptic and Arabic scripts, with Arabic translations featured prominently in the right-hand margins. The main text was written in Bohairic Coptic with Arabic placed in the right-hand margins and is accompanied by limited headings in Greek. These bilingual texts are commonly found in the Coptic liturgical tradition, and are considered to be one of the oldest divisions of manuscript production examined by specialists.[3] Coptic, based on the ancient Egyptian language, continues to be used in church manuscripts to this day, although as a spoken language its use has been limited since about the seventeenth century. The Arabic contained within the text has been interpreted as vernacular Arabic, though there have been a few deciphered anomalies within the text which may be a result of the "Arabization" of Coptic words and phrases by manuscript copyists.[4]

While the majority of manuscript copyists working in this era were considered professionals, there are several sections within the Agpeya that can be described as exhibiting evidence of "sloppy transcription."[5] Often, it was not necessary for a scribe of Coptic manuscripts to fully understand the language he was copying, and usually the mastery of the shapes of Coptic letters in their proper positions was enough to attain the status of calligrapher.[6] This fragment may have been created by either clergy or lay members as both groups were involved with the copying, production and patronage of manuscripts during this particular period.[7] Historians refer to the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries as a time of Coptic religious resurgence that included a sharp increase in manuscript production.[8]

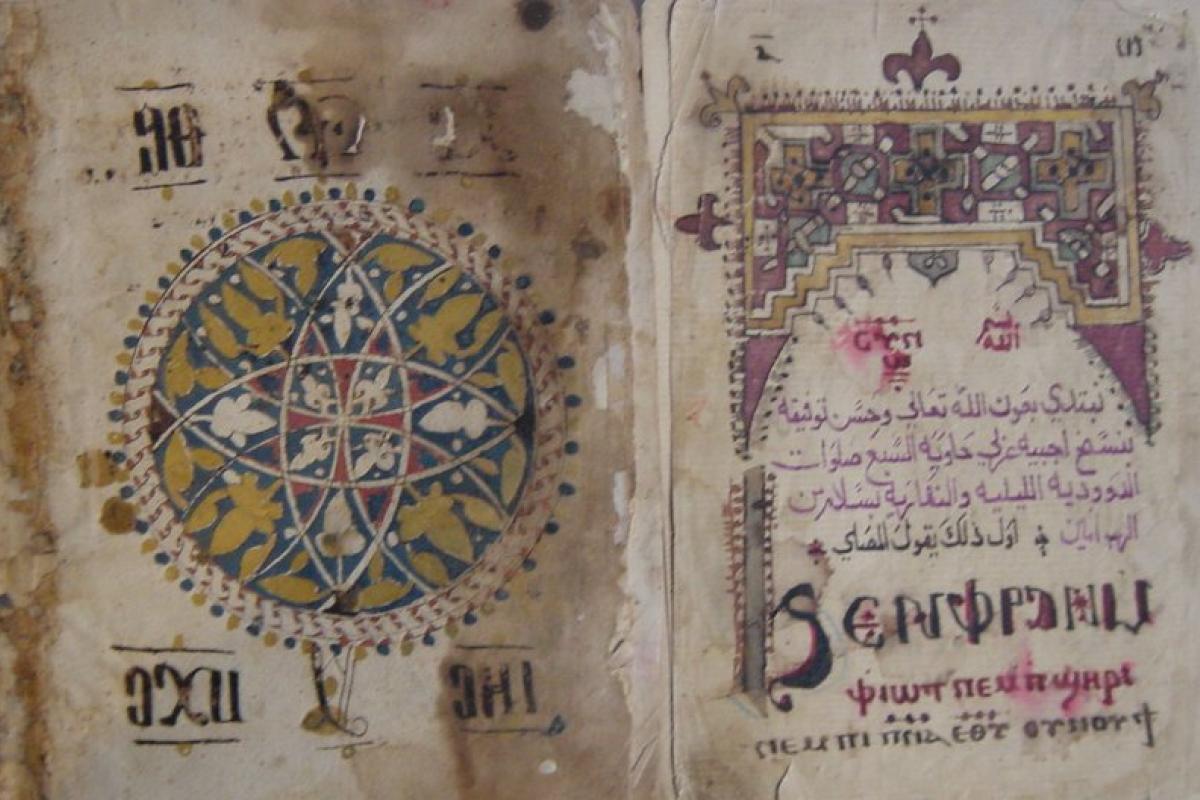

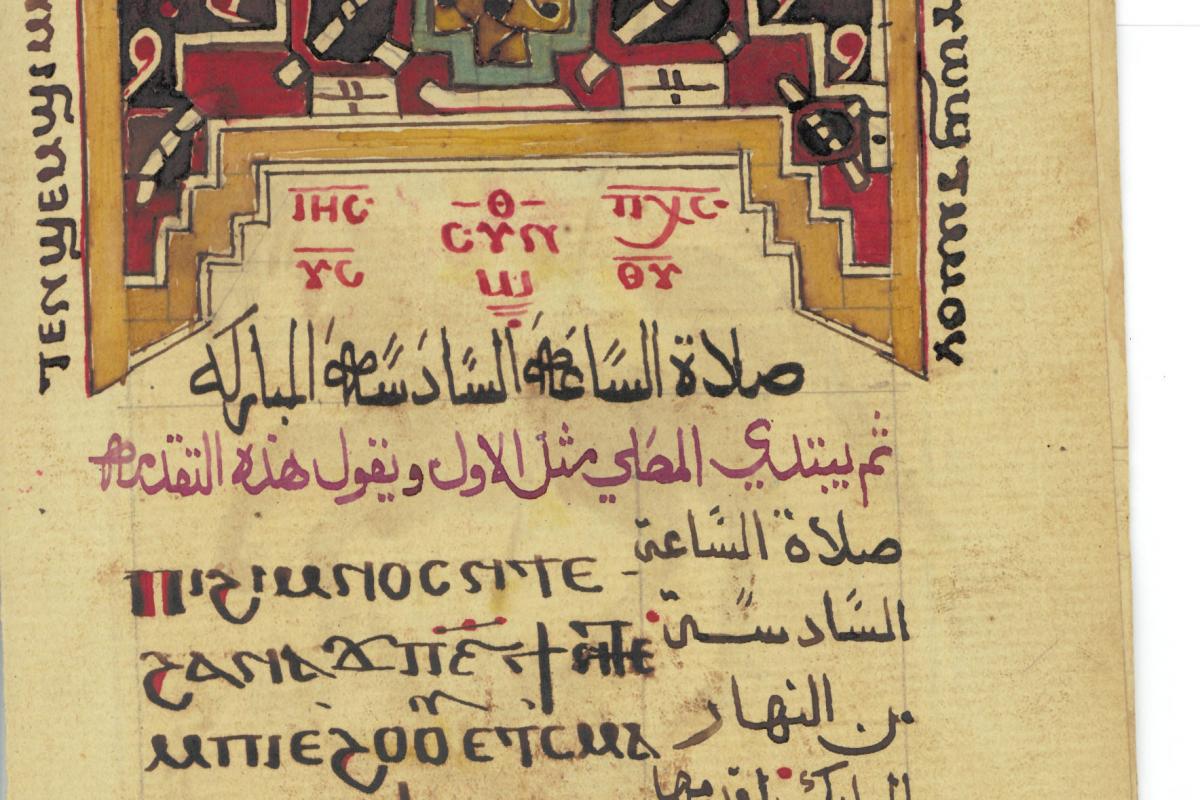

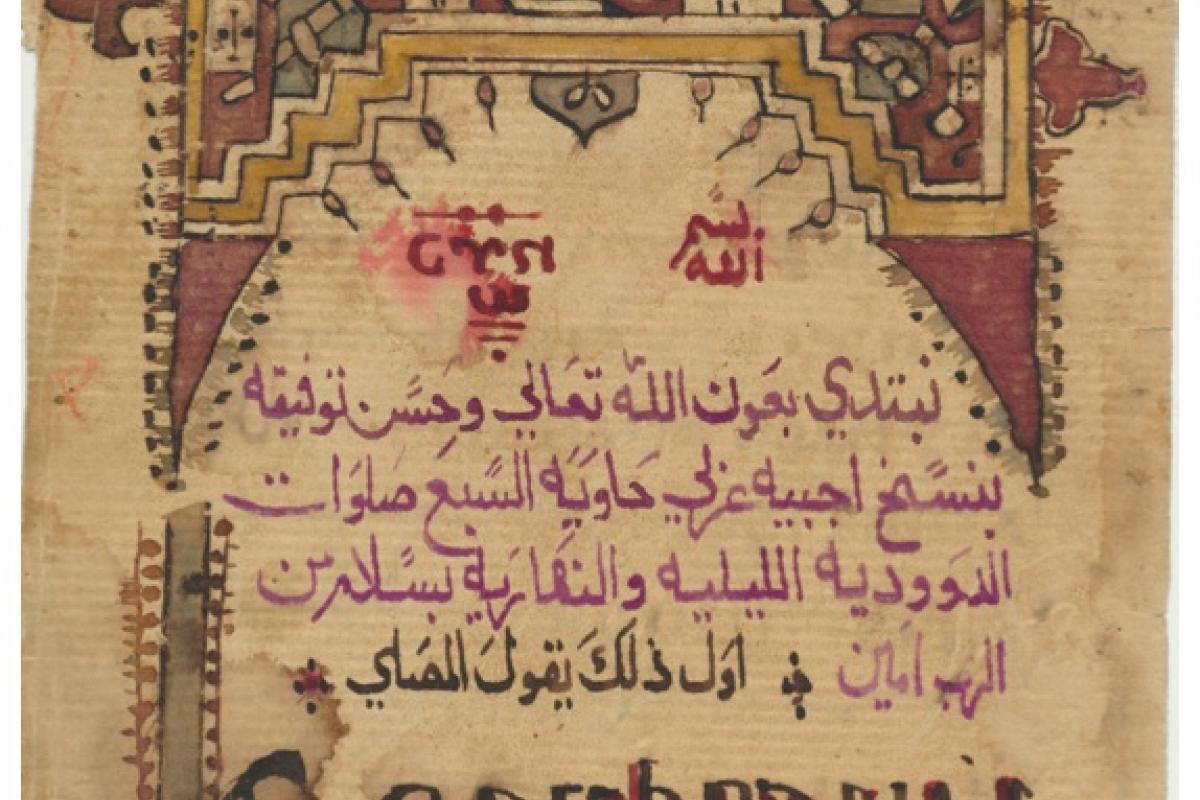

Within this Agpeya, the individual chapters of the Daily Office are clearly marked by beautiful illuminations of decorative archways similar to designs found in the Islamic tradition. Possessing a decided visual weightiness, these archways were rendered with a great deal of attention toward establishing a balanced overall geometry not just within the design, but throughout the entire manuscript. Each archway is unique in its appearance, though all share heavy interlacing, geometric repetition, dotted borders and a vivid array of coloring within the design. Among these pages, rubrication, or, red highlighting, marks the overall transitions within the text as well as the subject headings and content.

Like the warrior saint images which accompany these leaves, the color palette of the illuminations is robust, yet limited to the hues of yellow, green, purple, red, black and blue. The manufacture of colored inks for manuscript production was typically in the charge of monks working in monasteries who often added gum arabic to the pigments as a stabilizing agent for watercolor paints. Paint was typically applied with slender wooden reeds, with black ink usually reserved for text and red for the writing of book titles and chapter headings such as it is in this artifact.[9]

While the Agpeya does possess various physical imperfections which can be credited to its age and intended function, the overall condition of the vellum paper of the manuscript is good. This can be credited to a Coptic tradition of boiling vellum pages with powdered fenugreek and salt in order to stave off the destruction by insects and other pests which may eventually compromise the integrity of the paper.[10] This feature is important as it is demonstrative of the perceived importance of the artifact and its intended use and function within a cultural context. The care the calligrapher took in creating both the illuminations and text, as well as how we know the Agpeya was intended to be used by its owner, speaks of its inherent preciousness and power.

Notes

[1] Ra'uf. Habib, Classical Mythology in Coptic Art (Cairo: Mahabba Bookshop, 1970), 2.

Historically, Coptic manuscripts were printed upon a type of parchment paper derived from the skins of gazelles which was then cured until appropriate for the task of writing. It was not uncommon for old parchment papers to be erased and later re-appropriated by scribes, resulting in the loss of what is assumed to be a large amount of significant literary and historic texts.

[2] Suzanne Lewis, "The Iconography of the Coptic Horseman in Byzantine Egypt," Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt. (1973) 10: 27-63.

Eastern Christian art was generally expected to adhere to a strict iconographic tradition wherein artistic adaptations to visual imagery were not generally approved. The horseman imagery present in this Agpeya fit in with this Eastern hagiographic tradition and may have been copied from pattern books.

[3] Habib, Classical Mythology, 2.

Bilingual liturgical texts originally appear in the Coptic tradition before the recorded Arab Conquest of 642 AD.

[4] Dirgham Sbait, Interview by Professor Anne McClanan and author. Oral Interview. October 31, 2011.

Transcript available at PSU Library Special Collections.

[5] Sbait, Interview by Professor Anne McClanan and author.

[6] El Shaheed Smiha Abd, El Nour Abd, "Copyists and the copying of Manuscripts in the Coptic Church," Bulletin de la Societe d'archeologie copte 44, (2005): 81-84.

[7] Febe Armanios, Coptic Christianity in Ottoman Egypt (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), 8-36.

[8] Armanios, Coptic Christianity, 8.

[9] Armanios, Coptic Christianity, 36.

[10] Armanios, Coptic Christianity, 5.

----------

Denise Loncar, Medieval Portland Capstone Student

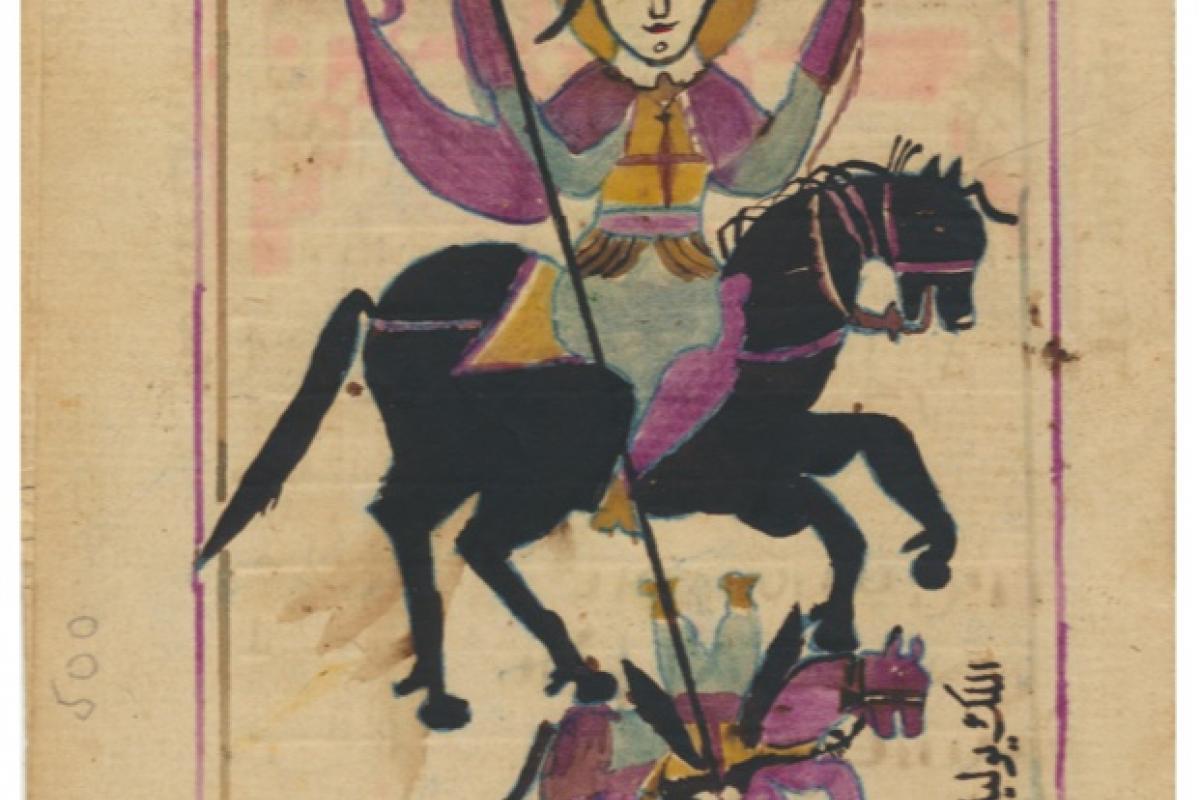

The images that accompany the readings from an early eighteenth-century Coptic prayer book, or Agpeya, are a testament to the nature of religious texts created in the Christian East. Eastern Christian religious art was generally expected to follow a strict iconographic code, within which adaptation or change was not viewed as desirable. Here the images of warrior saints, Saint George, Saint Theodore the Eastern, and Saint Mercurius, not only fit within the hagiographic tradition, but may have been copied from pattern books circulating during the period.[1] Especially popular in Coptic Christian Egypt, equestrian saint's images and relics were commonly believed to possess apotropaic, or protective powers. Others have also noted that rider saint figures often represented guardian imagery and were frequently rendered in pairings or groups.[2] This could be one possible explanation for the parallel images included in this manuscript.

On these pages, each of the three saints is represented by a particular set of symbolic imagery. The mounted Saint George is easily identified by the dragon underfoot which he spears with his pike. Saint Mercurius, also known in Arabic as Abu Sifayn, is recognized by the dual swords he wields overhead, while below, Julian the Apostate lays lifeless beneath the hooves of his mount. The final image portrays Saint Theodore the Eastern dethroning the Roman Emperor Diocletian, famed for his intense persecution of Christians, with a cross-topped spear. All three saints enter the scene piercing their targets from the left, while each victim occupies the lower right register on a blank field. Presented as simplified forms here, the warrior saint has become a legible "type" created with limited, but commonly understood signifiers.

Mounted warrior saints, especially prevalent in Egypt after the Crusades, had been portrayed in church frescos, sculptures, and woven into fabrics as early as the sixth or seventh centuries. But after the region became Islamicized, and Copts existed as part of the Christian minority, these images became increasingly important. One scholar notes that although Copts portrayed their most beloved martyrs as equestrian warriors, they themselves, were forbidden to own or ride horses under Ottoman rule. It is generally thought that to Coptic Christians, mounted warrior saint figures represented spiritual victory over the forces of darkness, while symbolically guarding against religious persecution.[3]

Notes

[1] Tania C. Tribes, "Icon and Narration in Eighteenth-Century Christian Egypt: the works of Yuhanna al-Armani al-Qudsi and Ibrahim al-Nasikh," Art History 27, 1 (February 2004): 69, http://web.ebscohost.com.proxy.lib.pdx (accessed 2 Oct. 2011).

[2] Bas Snelders and Adeline Jeudy, "Guarding the Entrances: Equestrian Saints in Egypt and North Mesopotamia," Eastern Christian Art, 3(2006):107.

[3] F.A. Meinardus, Coptic Saints and Pilgrimages, (Cairo: American University in Cairo Press, 2002), 33.

----------

Study Guide: Rachel R. Correll, Medieval Portland Sophomore Inquiry Mentor Project, Spring 2012

The Object

These leaves are fragments from an early eighteenth century Agpeya, or a Coptic Book of Hours. Similar to the book of hours in the Western Christian tradition, this manuscript includes prayers meant to be read by a Coptic priest at certain hours of the day (collectively called the Daily Office which focuses on the life of Jesus Christ). The manuscript itself was made by either clergy or the laity who are unordained religious members of the church. It was handmade on vellum measuring 19.5 by 13.7 cm. This object was made during the Ottoman rule in Egypt and is representative of manuscript production during that period.

The Text

This is a bilingual manuscript with Bohairic Coptic (read left to right) on the left and vernacular Arabic script (read right to left) on the right of the leaves. The Coptic language is based on ancient Egyptian and is spoken by Copts in Egypt. Bohairic is a dialect of Coptic that was adopted by the Coptic Orthodox Church as the liturgical language (much like Latin was for the Roman Catholic Church). Rubrication, or the use of red ink, designates section headings as well as transitions in the text. Red and purple dots are used in the Arabic script as vocalization markers, a characteristic also commonly found in Qur'anic manuscripts.

The Warrior Saint Images

The three main illuminations in these fragments are the warrior saint images. In accordance with Eastern Christian religious art, these follow a strict iconography in the manner in which they are depicted. The format of each image, therefore, is very similar, depicting the saints with garments flowing behind them, mounted on horses, and piercing their foes who occupy the lower right of the image field. Each saint is depicted with his common attribute and thus St. George conquers the dragon, St. Mercurius holds two swords over his head while conquering the last non-Christian Roman Emperor Julian the Apostate, and St. Theodore the Eastern uses a cross-topped spear to vanquish the Roman Emperor Diocletian, the persecutor of the early Christians. Mounted warrior saints were considered to have apotropaic powers in Coptic Christian Egypt, which meant they were seen to protect against evil forces. They were likely meant to represent the triumph of Christianity.

The Decorative Archways and Other Ornamentation

While the warrior saint images fall within the Eastern Christian tradition of visual depiction, the various ornamental details throughout the manuscript inherited characteristics from the Islamic artistic tradition, which emphasizes non-figural representation. The five ornamental archways introduce each chapter of the Daily Office and have dotted borders, geometric repetition, and bright colors. Floral rosettes, decorated initials, and vocalization markers balance the stunning visual appeal of the archways as they are scattered throughout the rest of the text.

Source

Bronwyn Dorhofer and Denise Loncar, "Agpeya," The Gift of the Word, catalog, Spring 2012 exhibition, Portland State University Millar Library Special Collections.

Inquiry

Why do you think horseback warrior saints were considered to have protective powers in their depictions? What is the significance of St. George spearing a dragon and how does it relate to the other two saints spearing non-Christian Roman Emperors? Consider the ornamental decorations, the warrior saint images, and the two languages of the text. How do they all relate visually? Is the manuscript successful in integrating multiple languages and artistic traditions? Can you find some of the dots used as vocalization markers in the Arabic script? How do you think the protective nature of the warrior saints and their representation of the triumph of Christianity relates to the text of the Daily Office which details the life of Christ?