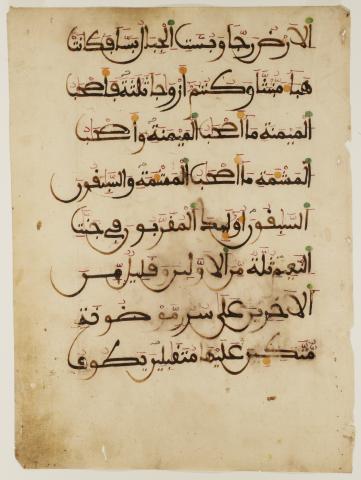

Qur'an Leaf in Magribi Script | Qur'an Leaf in Kufic Script

Qur'an Leaf in Magribi Script | Qur'an Leaf in Kufic Script

Islamic, 13th century or later

Single leaf

ink on paper

height 10-11/16 inches

width 7-3/4 inches

Portland Art Museum, The Vivian and Gordon Gilkey Graphic Arts Collection, 80.122.558

Kevin Wahlquist, Medieval Portland Capstone Student, 2005

This manuscript page renders 8 lines of Arabic text (translation unknown). As with all Arabic scripts, it is written right to left with a strict right margin. Despite an open right-hand margin, the script is remarkably even and proportioned. The last 3 lines have a slight downward slant as they conclude which might indicate that the page was written on after the manuscript was bound. The curvature of these lines seems consistent with the natural curve of a page within a bound book.

The richness of the calligraphic tradition allows an Arabic manuscript to be roughly identified in terms of time and place by the style of calligraphy used. The object in question was identified in the Gilkey Collection notes as 13th-century Kufic. After review, I believe that is mistaken. The script in question appears to be a form of Maghribi which is a western script used exclusively in Northwest Africa and Spain. This style has Kufic forms but differs in several meaningful ways. The curvature of the lettering is notably different than the more geometric forms of even the most cursive forms of Kufic. Also, the roundness of the sub-linear letters is quite distinctively Maghribi.

Maghribi scripts were developed directly from Kufic and in Tunisia, both styles are sometimes referred to as Kufic. It did not follow the traditions of Ibn Mulaq or al-Bawwab so it lacks the precise proportions and structure of those eastern styles. Western scribes were taught to write words as one, rather than forming each letter--another feature distinctive to the Maghribi manuscripts. Andalusian is traditionally a smaller form of Maghribi script but it cannot be considered strictly Iberian. Examples have been found throughout Moorish territories so it is quite difficult to distinguish which side of the strait an Andalusian manuscript is from. Dating a Maghribi script is also problematic. The style is remarkably consistent from the 8th century onward. One distinction is that it is commonly found in two sizes before the 16th century. The Andalusian being the smaller script with a larger ornamental version in use elsewhere. After the Moors were driven out of Spain, the two merged into a medium size that is consistent to this day.

One consideration is that vellum was used for Qur’ans much longer in the west so the fact that this manuscript is on paper might suggest a date considerably later than the 13th century. Vellum Qur’ans can be found as late as the 1700s. Of course, Moors had considerable paper-making technology in the 13th century so it is entirely possible that this manuscript could be that old. I have not found another example of a Maghribi Qur’an on paper from that early a date, however, so it could be considered unusual if not spurious.

The paper itself appears to be cut square and heavily textured. There are still binding holes along the right edge so it doesn’t appear the page was torn out. Islamic law proscribes strict rules for the destruction of the Qur’an. They are typically burned or buried to avoid desecration. The condition of the page might indicate that it was found in a “document grave.” Even a loose page would be treated with such care.

The brownish ink is also consistent with Maghribi manuscripts, as well as the red diacritical markings in a much finer hand. The manuscript also has large dots of blue, green, and red/orange ink. These are vocalization markings. Despite the efforts of codification in the 7th century, the inherent ambiguity of early Arabic scripts preserved the possibility that Quranic verses could be pronounced and articulated in a variety of ways. In Arabic, these variations of the vocalization of the same word can indicate a change in parts of speech, case, or even verb tense. The Islamic tradition allows for several authoritative recitations based on very strict traditions. The vocalization markings on the manuscript would indicate inflection, glottal stops, and other variations to remove any ambiguity from the text. From these markings, it may be possible to determine which of the 10 canonical or 4 non-canonical recitations of the Qur’an is recorded in the manuscript. These might make it possible to narrow the possibilities of the document’s origin.

Judging by the size, style of the script, and the fact that it is on paper, I suspect the manuscript in question is North African in origin. That it was identified as Kufic might also suggest a North African origin since it was common to refer to Maghribi script as Kufic, particularly in Tunisia. The date is questionable. I suspect a later date although the 13th century is not implausible.

Background Essay: Qur'an/Koran

The word Qu’ran means “recitation” which is indicative of its origins. The prophet Muhammad is traditionally believed to have been illiterate. The revelations given to him by the archangel Jibril (Gabriel) were recorded and memorized by his companions, who also hold an elevated status within Islamic tradition as the authoritative source for the Qur’an. Approximately sixty-five companions were used as scribes at one time or another before the Prophet died in 632 CE. The text is organized into 114 suras (chapters) and approximately 6,400 ayat (verses) depending on which tradition is considered authoritative. For the purposes of recitation and memorization, there are other divisions of the text into parts of equal length independent of the suras. Recitation and memorization are still vital to Islam.

It should be remembered that at the time of Muhammad, the Arabic tribes were disparate and contentious with considerable linguistic, cultural, and religious differences. The Qur’an (and the rise of Islam) not only marked the unification of these peoples but also became the basis for the unification of a written language system. Within 100 years of the Prophet’s death, they boasted an empire that stretched across North Africa into the Near East and even into Spain. Such rapid cultural changes caused considerable problems for the Qur’an as an oral tradition. As a Divine record, differences in recitation could not be tolerated. Therefore, the development of a systematic writing system is inextricably linked with the Qur’an. For example, the earliest Arabic scripts did not include vowel markings leaving a considerable amount of ambiguity in any written text. The need to preserve the Qur’anic message necessitated the development of later scripts which clearly indicated proper pronunciation and vocalization.

Tradition holds that the earliest compilation of the Qur’anic texts was during the rule of Abu Bakr. His successor, Uthman, commissioned a council to establish an authoritative codex and had all other versions of the Qur’an destroyed. Copies were then sent to each part of the Empire to be authoritative. This process is believed to have been completed by 656 CE.

Any depiction of a sacred personage is considered sacrilegious in Islam. The words of the Qur’an are also believed to be the literal word of God. For that reason, calligraphy is quite literally the highest form of sacred art in the Muslim world. From the time of Uthman, master calligraphers responsible for copying the Qur’an were the most revered artists of the Islamic world.

The earliest Quranic texts were written in Kufic script. Its form is geometric with each letter carefully formed. Lacking diacritical markings, the early Kufic script also introduced considerable ambiguity in the written text. The first cursive script Naskh was developed in the first decades of the 4th century by Ibn Muqlah. It was perfectly proportioned so that each letter bore a mathematical relation to the word and the text as a whole, but it was also cursive and allowed a gifted scribe to write quickly and easily. Not only was it scribe-friendly but it produced Qur’ans that were small enough to be carried. Naskh remained the dominant form of calligraphy until the 13th century. More Qur’ans are written in Naskh than all other calligraphic forms combined.

This script was later revised by Ibn al-Bawwab and named Thuluth. Again, perfect proportion was the major emphasis. Ibn al-Bawwab established a method of measuring letters by the number of dots a pen makes. This method of proportion allowed scripts to be developed in a number of sizes while remaining proportional. His system dominates the calligraphic tradition.

Over the centuries each generation would learn the calligraphic forms developed by earlier masters. New masters would establish their own forms and there arose regional schools and styles. As the number of forms increased, strict rules were established that indicated which calligraphic scripts were appropriate for which tasks. Some were reserved for Qur’anic art like thuluth and ornamental forms of Kufic. Others were reserved for Imperial edicts or royal correspondence by Ottomans.

Each style has strict rules and basic forms which comprise the letters. Some even have a proscribed size. The most popular were the proportional scripts which could be adapted to the task at hand while maintaining artistic sensibility. Although there are strict rules for the various styles, they do allow for artistic expression for the individual artist. The thickness of lines, the depth of sub-linear flourishes, the ratio of straight to curved letters, and the flow of the script all clearly separate the mere scribe from the artistic master.

In parallel to the development of calligraphy, the illumination of Qur’anic manuscripts is also a huge artistic tradition with tremendous complexity and variation.