Armenian Prayer Roll

Armenian, late 17th-early 18th century

Constantinople (Istanbul), Turkey

ink on vellum

length 478.7 cm | width 12.7 cm

Portland State University Library Special Collections, Mss 38

----------

Darcie Hart Riedner, PSU's "Gift of the Word" Exhibit, Spring, 2012

The Armenian prayer roll holds a special place in Armenian culture and worship. Prayer rolls such as this were highly treasured, theologically sacred manuscripts representing the very personal nature of prayer in devoutly Christian Armenia.

Amulet, talisman or magic scroll all identify the apotropaic nature for which prayer rolls were known and used for centuries in Armenia. Armenian people possessed a strong belief in the power of the written word. It was thought events could be influenced by writing the desired cause or effect on a long, narrow scroll called a hymayil, meaning literally "charmer."[1] Utilizing the accepted format of a long narrow roll of vellum or parchment, calligraphers and artists produced scrolls with prayers or personal intentions specific to the owner. Text and illustration could include prayers for safe travel, good health, prosperity in business, or for the wisdom of the nation's leaders. Personal requests might range from the relief of headaches or poor vision to intentions for a family member. Prayers for assistance might be directed to Jesus Christ, the Virgin Mary, St. Stephen the Martyr or St. Gregory the Illuminator. Prayer rolls were believed to protect, prevent or neutralize evil and gain favor with the saints.[2]

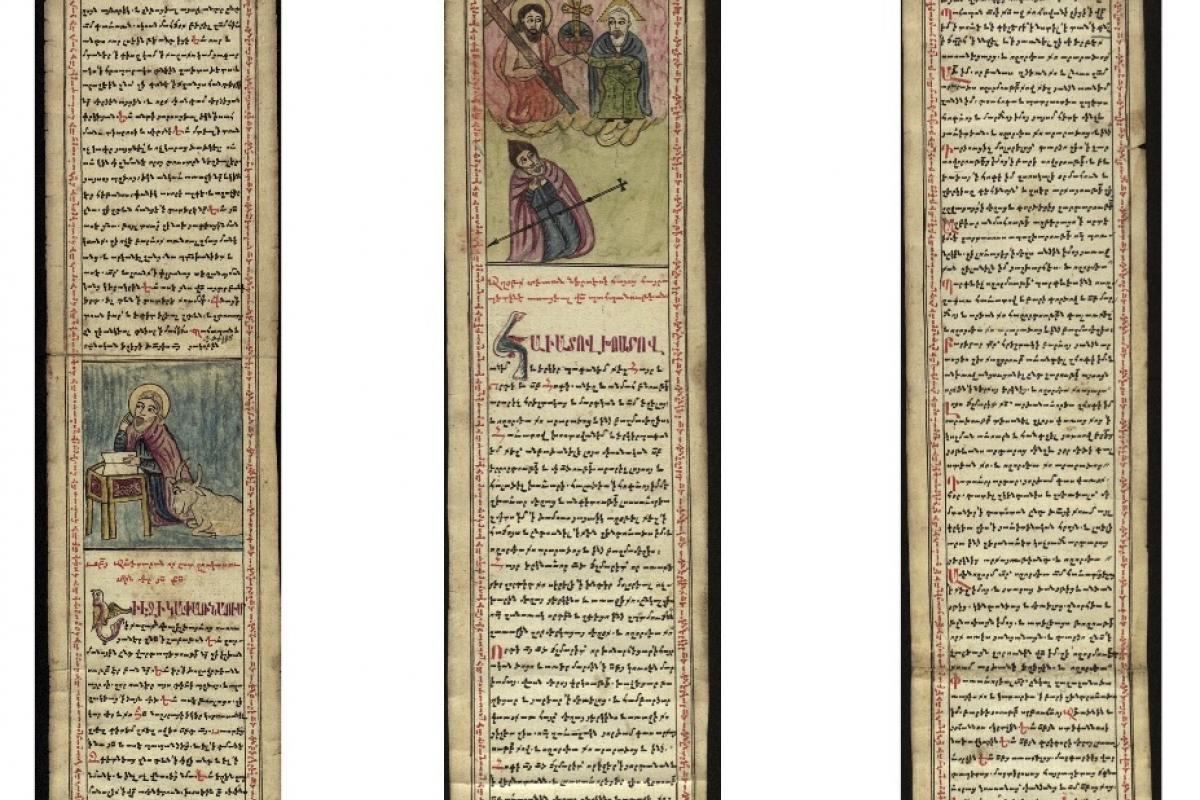

Sixteen panels of iconic Christian imagery and text comprise the contents of this scroll. The illustrations are drawn and colored in a primary color palette with blending and shading applied to create colors with religious significance, such as purple. Passages of text below each illustration are written in erkat'agir, an uncial script. Initial letters of paragraphs appear in either erkat'agir or stylized creatures such as birds, a traditional flourish in religious manuscripts. Black lettering was used for the script to symbolize the pain of original sin, while white space symbolizes the innocence of birth. Red ink was used to create what is known as a rubric, which provided information specific to an individual entry. The scribe might personalize the roll by adding anecdotes about working conditions or modest comments their skill and ability. Prayer rolls were important and valuable; it was standard practice for the owner to write their name within the script.[3]

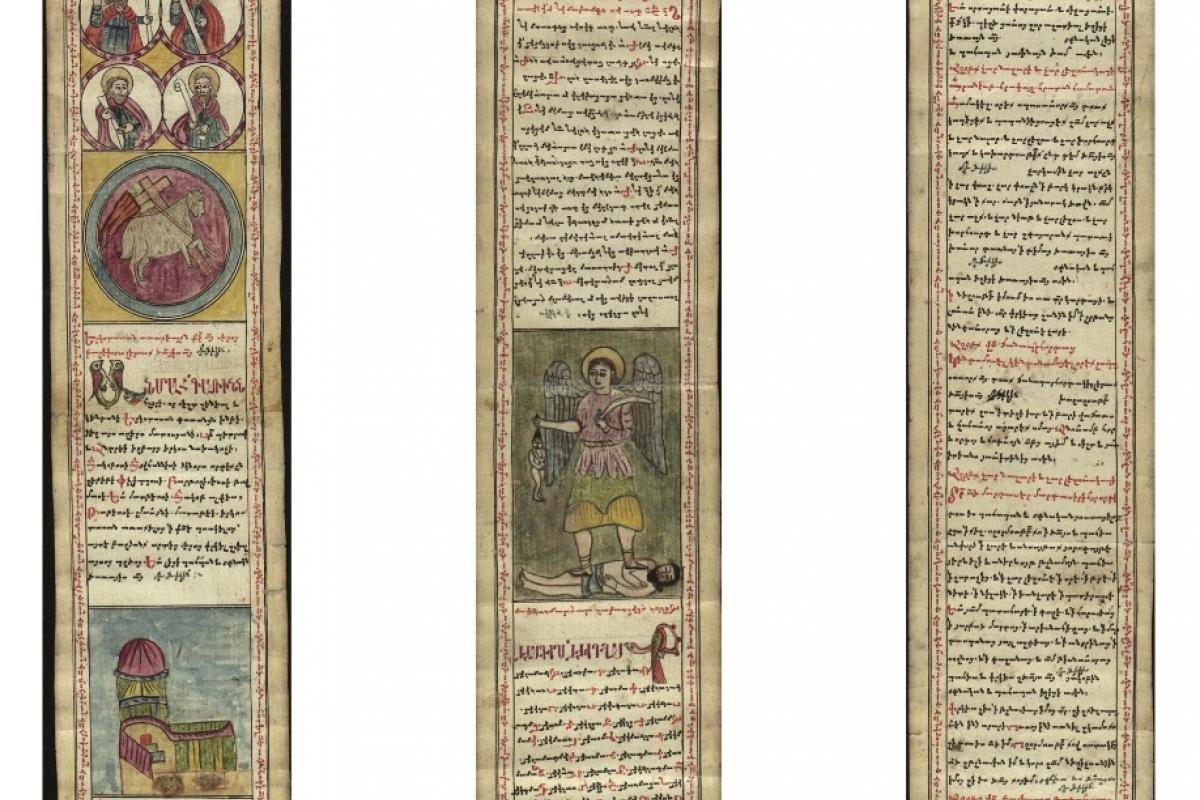

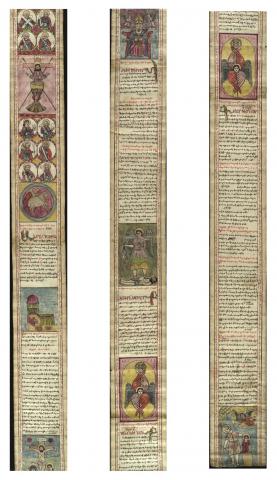

Illustrations, traditional prayers and overall form are similar elements within every Armenian prayer roll, but the message is honed to reflect the individual nature of each. The prayer roll in the Millar Library includes text from the Gospels of Mark, Luke and John all referencing miracles of Galilee, traditional prayers of the Armenian Church dedicated to St. Gregory the Illuminator and St. Nerses, illustrations of the Crucifixion, Virgin Mary with the Christ child and the Lamb of God.[4]

Notes provided by the antiquities dealer estimate the date of the roll at the late seventeenth to early eighteenth century based on the depiction of the Tomb of Christ, also known as the Holy Sepulcher, in one of the roll's illustrations. The last panel on the roll is missing a section, which would provide the colophon containing the name of the scribe, exact date and place of composition. The creation of a prayer roll by a scribe and artist was in decline by the mid-nineteenth century with the majority of these works produced on printing presses at that time. The practice, as a whole, died out over a century ago.[5]

Notes:

[1] Hamlet Petrosyan, "Armenian Folk Arts, Culture, and Identity." (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2001), 58.

[2] Edda Vardanyan, Arme'nie, la magie de l'e'crit, ed. Claude Mutafian, ( Marseille: Musees de Marseille, 2007), 123-125

[3] Dawn Stevick, "Notes." (University Studies Capstone Course: Medieval Portland. 11 Aug. 2011).

[4] Father Garabed Kochakian, email correspondence with author, 3 Nov. 2011.

[5] Dr. James Russell, Professor of Armenian Studies, Harvard University, email correspondence with author, 16 Nov. 2011

----------

Brian Horn, Darcie Riedner and Dawn Stevic, Medieval Portland Capstone, 2011

PSU Millar Library Special Collections has recently acquired an Armenian prayer roll. It has been tentatively dated to late seventeenth to early eighteenth-century Constantinople. The roll contains 16 religious images related to Christ and the Evangelists with black and red script following the images.

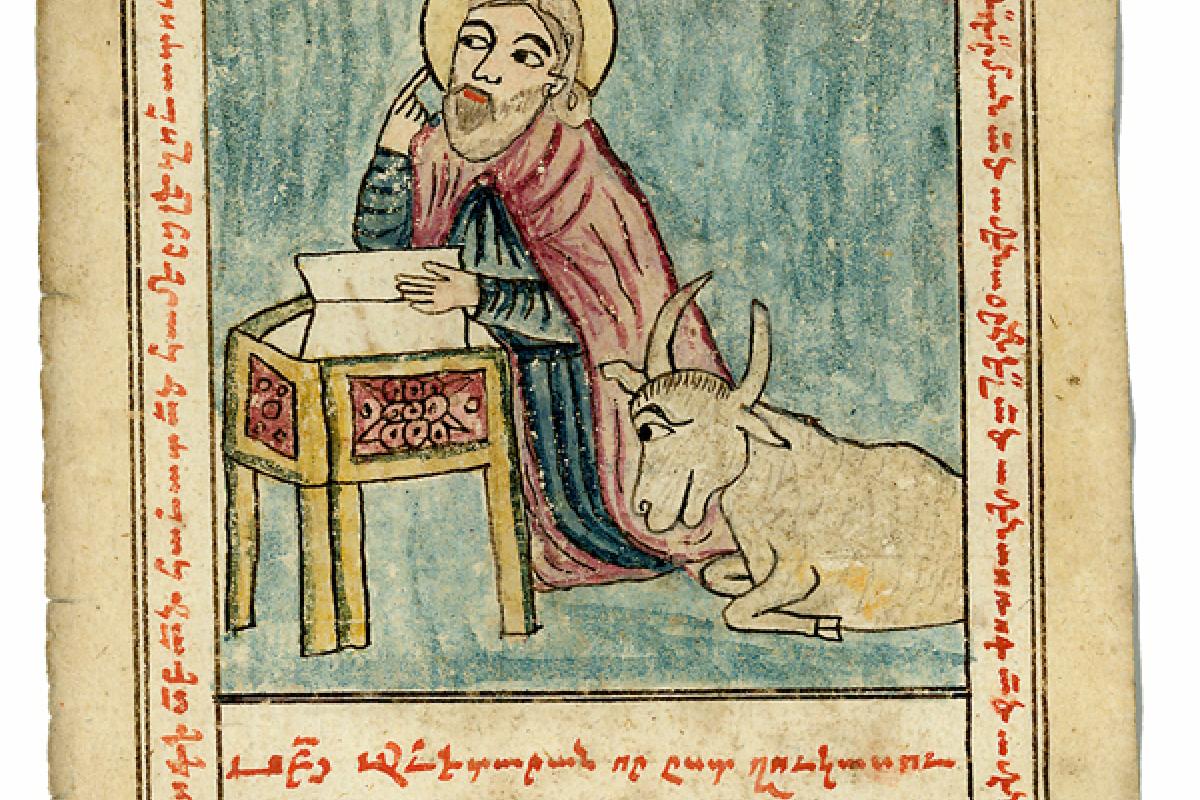

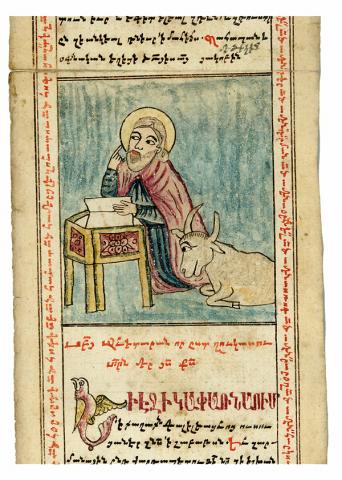

The first image on the roll renders St. Mark with a lion. St. Mark founded the first Christian Church in Alexandria. He also authored the first and oldest gospel and the Holy Eucharistic Liturgy, which is still used in Coptic Orthodox services today ("St. Mary"). Legend states lions are born dead and come to life three days after birth, so the lion represents the Resurrection and is the symbol for Christ, and of Mark because his Gospel focuses upon the Resurrection of Christ (Ferguson, 20, 21, 236). Numerous traits confirm the identity of St. Mark in this piece. St. Mark was the scribe and secretary for St. Peter, and as such is depicted at a desk with tools for writing. The image of St. Mark on the prayer roll precedes panels with illustrations of St. Luke and St. John, respectively, following the order of the books of the Gospel in the New Testament and a lion is pictured sitting at his feet. Armenian scholar Dr. Vrej Nersessian explains the lion can represent passion and is pictured with St. Mark by whose teaching our passions are taken under control, directed against evil and toward good deeds. The message below St. Mark's illustration is from the Gospel of Mark in the New Testament Chapter 6:45-48 (see Appendix).

Other images that bear some similarities to #4299B can be found in a portrait of Saint Luke cited in Treasures in Heaven: Armenian Art, Religion, and Society by Annemarie Weyl Carr. Regarding the border motif, she indicates that a "thin white line ... punctuated by pairs of quickly sketched paired white marks" is a motif seen on Venetian manuscripts. She also notes that the first known appearance of this pattern in Armenian manuscripts was in the Zeyt'un Gospels, most prominently in the Evangelists' portraits (107-9).

In addition to the symbolism inherent in its imagery, there is a metaphorical nature to the materials and lettering of the Armenian scroll. "Erkat'agir" is a large uncial script appearing below the artwork. Initial letters of paragraphs tend to be in the erkat'agir script or of different stylized creatures. (Steyn, 19), (Sanjian, ix) The chapters are written in notr'gir notary script. Black lettering was used for the chapters, symbolizing the pain of original sin, while the white paper space symbolized the innocence of birth. (Malayan) Red ink was used to draw attention to certain areas, sometimes known as a "rubric." Lettering in red at the beginning or at the end of a script is the colophon, providing information about the scribe, the artist, and where, when, and for whom the roll was made, and may be continued in the margin surrounding the manuscript (Stone). It was standard practice for the owner of the manuscripts to write their name in the script in the roll (Steyn, 3). In conclusion, while the Armenian diaspora dispersed Armenians far and wide, the prayer rolls and illuminated manuscripts were ever guarded as prized possessions; about 25,000 of these manuscripts survive, providing an important and rare look into Armenian culture, religion, knowledge and art.

Appendix:

The passage translated by Ter Yeghia Isavan, a priest from Saint Kevork Armenian Apostolic Church of Oregon, reads:

And straightway he constrained his disciples to enter into the boat, and to go before [Him] unto the other side to Bethsaida, while he himself sendeth the multitude away. And after he had taken leave of them, he departed into the mountain to pray. And when even was come, the boat was in the midst of the sea, and he alone on the land. And seeing them distressed in rowing, for the wind was contrary unto them, about the fourth watch of the night he cometh unto them, walking on the sea; and he would have passed by them.

Bibliography:

Evans, Helen C. Treasures in Heaven: Armenian Art, Religion, and Society. New York: The Pierpont Morgan Library, 1998. Print.

Ferguson, George. Signs & Symbols in Christian Art. New York: Oxford University Press, 1954. Print.

Malayan, Ruben. The Art of Armenian Calligraphy. (10:43 a.m., July 1, 2011) http://15levels.com/art/armeniancalligraphy/ (Accessed July 09, 2011).

Sanjian, Avedis Krikor. Medieval Armenian manuscripts at the University of California, Los Angeles, Volume 14. ix. Los Angeles: University of California Press: 1999. Print.

Steyn, Carol. Pretoria's Golden Gospel Book: A study of a luxury seventeenth-century Armenian manuscript. Pretoria: University of South Africa, 2007. Print.

Stone, Lesley. The illuminated Manuscript. University of South Florida, Tampa library Special Collections. YouTube upload by USF Libraries, 02/18/2008. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ldVk6ZhFmhQ&feature=related (Accessed July 09, 2011).

"St. Mary and St. Antonius." "Coptic Orthodox Church. The Coptic Church. "St. Mark the Founder." (Milwaukee, Wisconsin, 2009) http://www.wiscopts.net/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=81&Itemid=90&limitstart=1 (Accessed July 10, 2011).

----------

Rachel R. Correll, Medieval Portland Sophomore Inquiry Mentor Project, Spring 2012

Study Guide:

The Object

This is an example of an Armenian prayer roll from Constantinople, likely made in the late seventeenth to early eighteenth century. The long narrow vellum scroll, called a hymayil ("charmer"), consists of sixteen panels of Christian images and text and measures 12.7 cm by 487.7 cm. These prayer rolls were thought to have a protective power and the prayers and texts included in them often directly related to the needs of the owner who would likely keep it close at all times. Armenians believed the written word contained inherent power and thus used prayer rolls for centuries in order to ensure a variety of results such as relief from illnesses, safety while traveling, and prosperity in business. The themes of salvation and resurrection are rampant in the prayer roll as seen through the Christian imagery and text.

The Text

The letters are written in a notary script, notr'gir, while the section headings are in an uncial script, erkat'agir. Some of the initials appear as stylized animals, a characteristic common in religious manuscripts. Another common device is the use of red ink to draw attention to section headings and other important information. The margins include text in red ink that runs down the whole length of the scroll. The text includes biblical passages from the Gospels of Mark, Luke, and John on the miracles performed by Christ in Galilee as well as traditional Armenian prayers dedicated to Saint Gregory the Illuminator and Saint Nerses IV.

The Images

The primary color palette of the images is balanced by symbolically significant colors such as purple which symbolizes Christ's resurrection. The first three images are of Saints Mark, Luke, and John with their animal symbols, the lion, bull, and eagle, respectively. The sixth image is of Christ enthroned with his fingers in the gesture of blessing known as the Monogram of Christ as his fingers form the abbreviation for Jesus Christ in Greek: ICXC. Next are six roundels with the apostles of Christ depicted in blue robes with their attributes. Saint Peter is the first, as he was the first called by Christ to be an apostle, and he holds the keys to Heaven, his most common attribute. The next image is of a purple-robed Christ rising out of the chalice, symbolizing his resurrection and the salvation made possible for Christians because of his sacrifice. This is followed by six more roundels of the apostles. As each apostle is depicted similarly in a blue robe with a red cape and in a round frame, they are connected visually though they appear throughout the scroll. Next is the Lamb of God, a symbol for Christ, holding the red standard (or flag) that also symbolizes Christ's resurrection. Other scenes include Saint Nerses IV observing the Holy Trinity, the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, the Crucifixion (with Adam's skull at the base of the cross), the Virgin and Child, Saint Gregory the Illuminator enthroned with angels crowning him, a seraph with six wings, and Abraham sacrificing Isaac.

Source: Darcie Riedner, "Armenian Prayer Roll," The Gift of the Word, catalog, Spring 2012 exhibition, Portland State University Millar Library Special Collections.

Inquiry

Is it significant that this is in scroll form versus a codex (e.g. manuscript) form? Look at the apostles and how each carries an attribute in order to identify himself such as Saint Peter with his keys. Can you name any of the attributes or the apostles? Why do you think the artist depicted each of the apostles in order of when they were called by Christ to serve? The biblical passages included in the roll describe some of the miracles Christ performed. How do you think this relates to the protective nature of the prayer roll? What are the benefits of this protective object being in the form of a narrow roll?