The City of God | De Civitae Dei

De Civitae Dei|The City of God

German (Mainz), 1473

Author: Augustine, Saint (Roman bishop, theologian, 354-430)

Printer: Schöffer, Peter (German printer, ca. 1425-1502)

Language: Latin

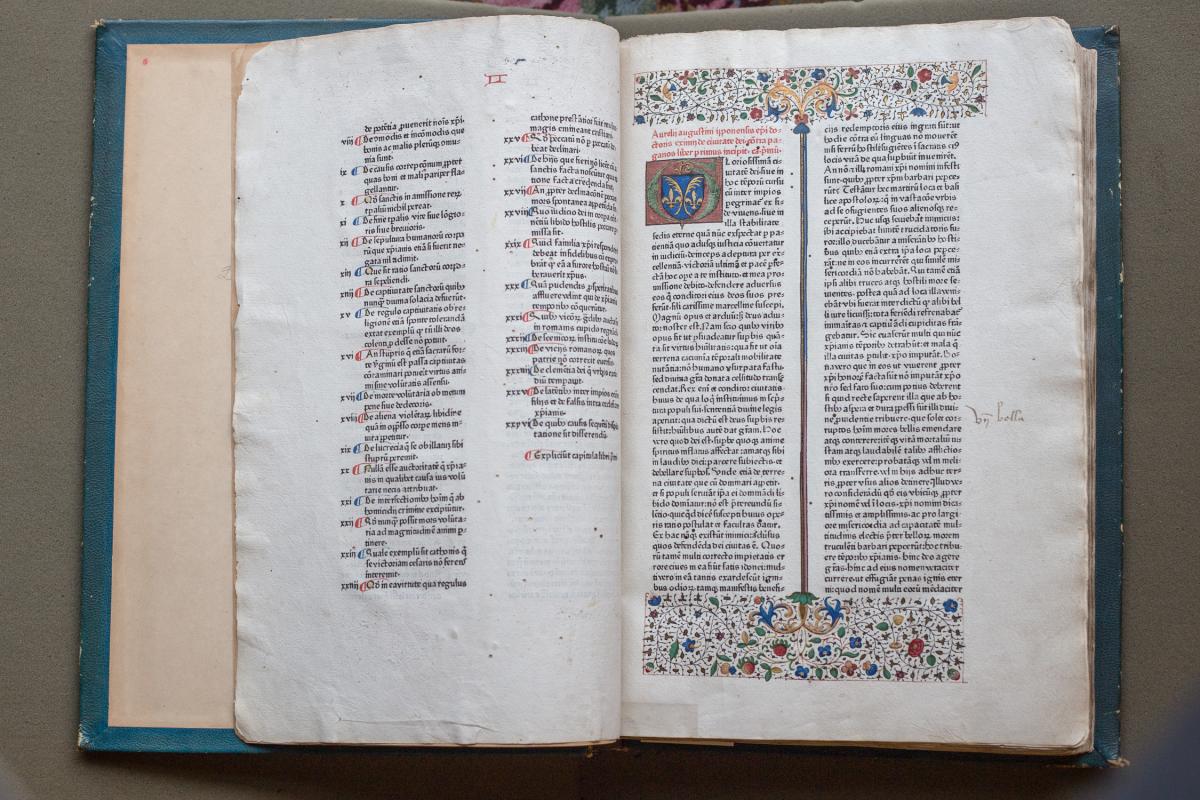

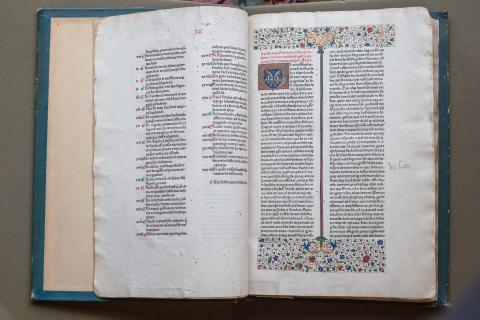

Fols. a1v-a2r: Table of contents and beginning of book 1.

Multnomah County Library, John Wilson Special Collections: W093 Acs. No. 640

Diebold, William. The Illustrated Book in the Age of Printing: Books and Manuscripts from Oregon Collections. Portland, OR: Douglas F. Cooley Memorial Art Gallery, 1993, cat. no. 16, p. 8 - Quoted with permission

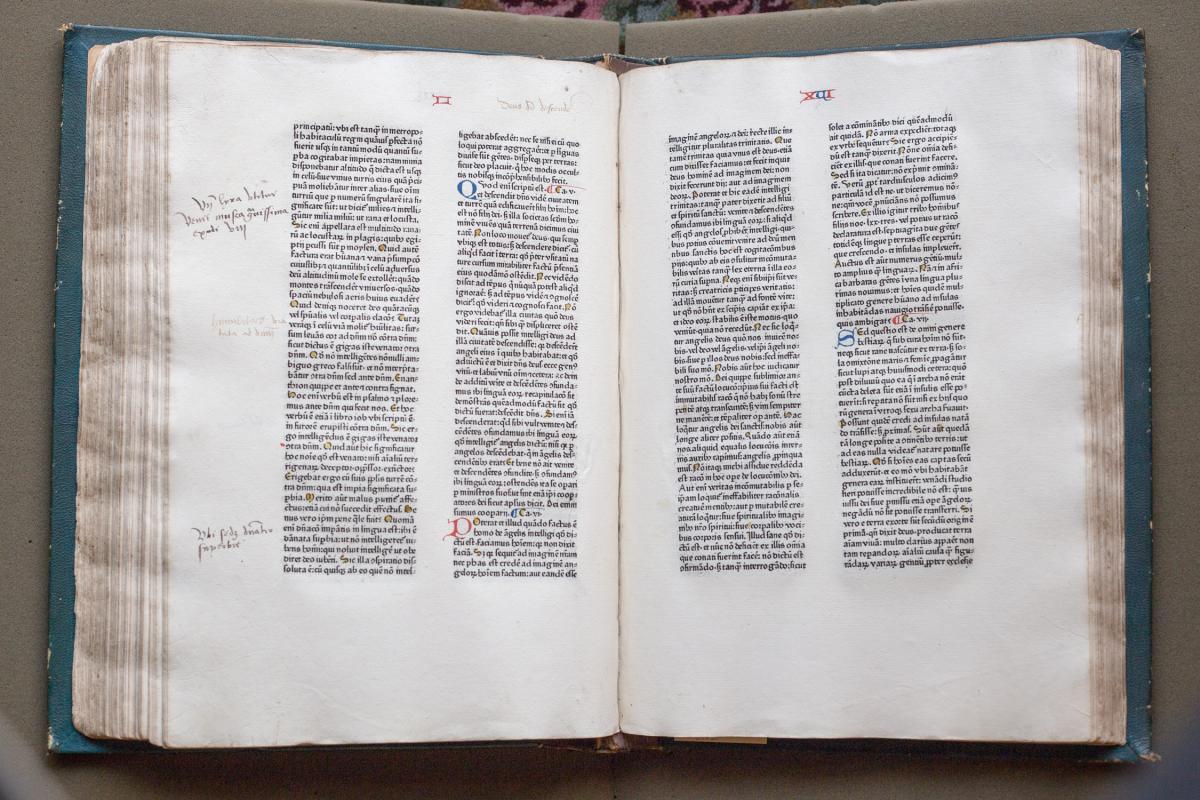

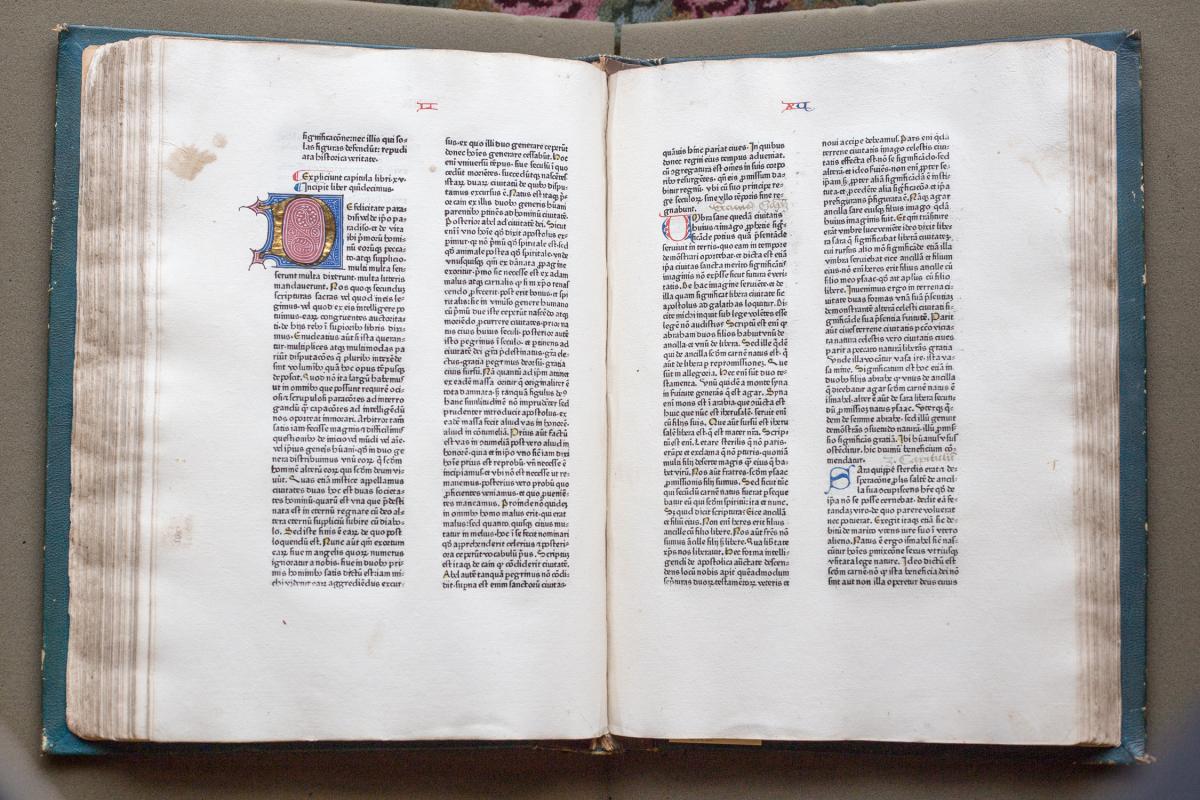

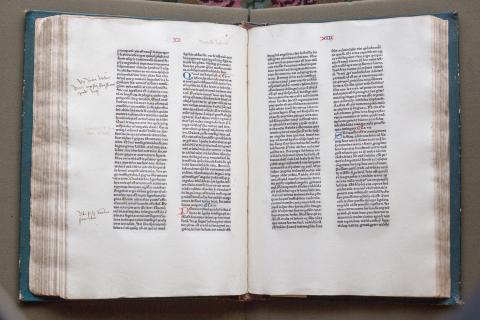

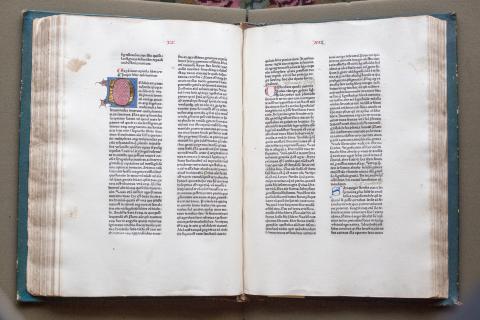

This opening shows the (to us) surprising relationship between hand-made and printed decoration that is characteristic of early printed books. On the verso, the red and blue paragraph marks were added to the printed text by hand, as was the dot of yellow paint in the first initial of each chapter heading [refers to page on display in exhibit from which this text was a catalog entry]. On the recto, the brightly-colored initial ""G"" with the coat of arms of an early owner (as yet unidentified) and the border decoration were painted by hand, but the entire text, including the first three lines in red, was printed. Color printing in this period was an ungainly process, usually involving the sheet being placed in the press twice. That technique was used in this book, as is apparent from the slight deviation in the registration (alignment) of the red and black lines.

Although there are no examples of the work of Johann Gutenberg in this exhibition, this book brings us very close to the invention of printing. It (along with numbers 17 and 22) was printed by Peter Schoffer. Originally a scribe, Schoffer became an assistant in Gutenberg's Mainz printshop. After Gutenberg had to give up printing because of his inability to pay the judgment in a lawsuit brought against him by his partner and patron, Johann Fust, Schoffer went into business with Fust (and later married his daughter). Schoffer worked as a printer in Mainz until his death in the first years of the sixteenth century, when his workshop was taken over by his son Johann, the printer of number 36.

Ted Williams, Medieval Portland Capstone Student, Summer 2005

This 15th-century copy of Augustine's De Civitate Dei (The City of God) was published by Fust and Schöffer. The text has been rebound in a green 19th-century style cover with the Fust and Schöff printer's mark emblazoned in gold on the front cover. The introduction and table of contents are still included and all pages are in remarkably good condition. The text is fully illuminated (hand-lettered capitals on each page) in black, red, blue, and sometimes gold; no credit has been given to the illuminator. The first letters of each paragraph and chapter alternate between red and blue (rubrication) throughout the text. This rubrication appears to be done by hand, rather than using Schöffer's multi-color printing technique. Each paper page has two columns of black lettering with 45 lines of fully justified text. The text is uniform and is printed, using movable type, which mimics a handwritten script. The red publisher's mark (Fust and Schöffer) with a date of 1473 appears on the final page of the manuscript. Additionally, the manuscript does not begin with the starting line of the published Latin of the City of God. The third page is elaborately illuminated and appears to be a new section, but neither does it start the text of the City of God. One or both of these sections may be the commentaries of Nicholas Trevet and Thomas Waleys, and this is a topic that warrants further research. These two scholars were the only two writers known to appear in 15th-century printings of the City of God. These commentaries also appear in the 1473 manuscript by the same publishers appearing at Marquette University.

This manuscript appears to be an example of incunabula, manuscripts published before 1500 using movable type printing. There are several identifying characteristics for making this judgment. The first clues to the layperson are the consistency of the script, the ink, and the paper used. Another manuscript from the 15th century in the Wilson Room collection, Commentarium, is a wonderful contrast. In the handwritten manuscript, the writing, although precise, varies across volumes. The consistency immediately suggests printing.

Guessing that the manuscript was printed, rather than written by hand, generates several questions 1) Who printed the text 2) When was it printed 3) What type of printing was used. Much of the history of the text can be gathered by simply identifying the printer's mark. The two banners and broken twig are the printer's mark of Fust and Schöffer. This emblem is accompanied by the exact publication date of 1473. The printer's mark is an innovation of Fust and Schöffer, first appearing in Biblia Latina printed in 1462. This was not the only innovation by this publishing company. The precise year of publishing was first used in their landmark publishing of the Psalter in 1457. This publishing of the Psalter had a number of remarkable innovations. First, Schöffer used the movable printing techniques he used while studying under Gutenberg and the typeface (B42) he developed in conjunction with Gutenberg. Schöffer surpassed his master with the successful publication of a manuscript with multiple printed colors. Gutenberg's two-color works (black then red) required printing in one color, then reloading the page and printing the second color. Gutenberg abandoned this technique because it was too difficult (expensive) to align the two plates properly; the red was lettered by hand after printing. Schöffer's technique appears to have been inking the plate in black, removing the typefaces that were to be rubricated, inking them by hand in red or blue, replacing them, and then printing the entire page. It has been suggested that Gutenberg's technique of using separate plates was used in this manuscript due to an obvious offset between the red and black text. This offset was not visible to the untrained eye and seems odd, given the documentation that Schöffer and Fust had developed a higher quality, lower cost solution to the multi color printing problem years earlier. The illumination in this copy of the 1473 De Civatate Dei is not as elaborate as the one on display at Marquette University, but is still complete. This manuscript, although not as artistic as other pieces in the Wilson Rare Book Room, is an important text in the early history of publishing with movable type.

Suggestions for further reading:

- Latin text of the City of God at http://www.thelatinlibrary.com/augustine/civ1.html

- Augustine (413–426) The City of God (Dods, M. Trans.) Retrieved from http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/npnf102.iv.html

- Marquette University Rare Book Collection (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.marquette.edu/library/collections/archives/rare_books/incunabula.html

Suggestions for further reading on incunabula:

- Buhler, C. F. The Fifteenth-Century Book: The Scribes, The Printers, The Decorators. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1960.

- Hundman, S. Printing the Written Word: The Social History of Books, Circa 1450-1520. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1991.

- Kapr, A. Johann Gutenberg: The Man and his Invention. (Martin, D Trans.) Brookfield, VT: Ashgate Publishing Company, 1996.

- Stillwell, M. B. Incunabula and Americana 1450-1800: A Key to Bibliographical Study. New York: Cooper Square Publishers, Inc., 1961.

- Diebold, William. The Illustrated Book in the Age of Printing: Books and Manuscripts from Oregon Collections.: Portland, OR: Reed College Art Gallery, 1993.

Ted Williams, Medieval Portland Capstone Student, Summer 2005

Background Essay: Saint Augustine of Hippo and the City of God

Augustine was born to Patricius and Monica Herculus in 354AD in the North African city of Tagaste, now known as Souk Ahras, Algeria. Monica was a Catholic, but Patricius was not. Although Augustine was raised Christian, he did not embrace his mother's religion in his early life. He excelled in school studying and eventually teaching rhetoric. He met his long time mistress and the mother of his child in a brothel. As scandalous as this may sound today, this was a common practice of the times. It was not until Augustine moved to Milan and met Ambrose that Augustine wholeheartedly embraced Christianity. Ambrose was a powerful speaker and very influential in bringing Augustine to embrace his Christian heritage. In 387 AD he was baptized into the Church and shortly thereafter in 391 was ordained a Priest in Hippo. By 396 AD, he was a bishop. His first famous writing was the Confessions, which was started sometime around 397 AD. The sacking of Rome in 410 AD triggered (if not inspired) the writing of Augustine's City of God. Later in life, the date is unclear, Augustine wrote Retractions. This text is historically significant, as it lists, presumably all, of Augustine's writings in chronological order.

The City of God was, by all accounts, an ambitious work, synthesizing thinking on spirituality, philosophy, and the social order. An English translation of the text by Rev. Marcus Dods can be found at http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/npnf102.iv.html and other locations on the internet. The contents of the twenty-two books of the City of God are agreed upon. Many other points about the work are controversial. The first ten books deal with contemporary beliefs that worshiping various gods has been and can be used to prevent catastrophes. The unsettled feeling throughout the empire most likely prompted this discussion after the sacking of Rome in 410. In the next twelve books, Augustine brings to bare immense skill at rhetoric to reconcile the ideas of free will, divine omnipotence and justice, and the source of evil in a world created by an omnipotent god. The perceived success of these arguments varies greatly by reviewing the author.

Even a brief survey of Augustine's arguments is engaging. There is consensus that Augustine's arguments shaped church thinking. Augustine suggested that enlightenment does not come by searching our own hearts or any other earthly device. Rather, by turning our eyes and hearts outward to God, only then can enlightenment be found. Another theme was the difference between the City of God and the City of Man. Augustine expounded on the Biblical idea that the City of God resided in the hearts of the true follower of God, not in an earthly City (Rome), nor necessarily in the institutions of the earthly church. This doctrine has been used to both challenge and justifies separation of Church and State.

Augustine elaborated on the idea that Christ was the sole source of good in the world. This absolutism created a doctrine enabling persecution of other faiths or deviations from the one "True Church." The Crusades to the Middle East were among the most infamous. The inquisitions throughout Europe, most famously in Spain, were another such movement. Augustine's discussion of the absolute good of Christ is just one example of how his writings guided church doctrine during the medieval period.

Suggestions for Further Reading on Augustine:

- Bourke, V. J., Augustine's Quest of Wisdom. USA: The Bruce Publishing Company, 1945.

- Brown, P.R.L., Augustine of Hippo; a biography. University of California, Berkley, 1967.

- Collins, R.W. A History of Medieval Civilization in Europe. Boston, MA: Ginn & Company

- Scott, K.T. Augustine: His Thought in Context. New York: Paulist Press, 1995.

- Smith, W. T. Augustine, His Life and Thought. Atlanta, GA: John Knox Press, 1973.