Digest of Justinian

Digest of Justinian

Italian, 1477

Compiled by Tribonian at the order of the Emperor

Printed by Jacobi Rubeorum

Binding contemporary with the piece. Endpapers have come unglued, revealing

Language: Latin

Jackie Brooks, Medieval Portland Capstone Student, Summer 2014

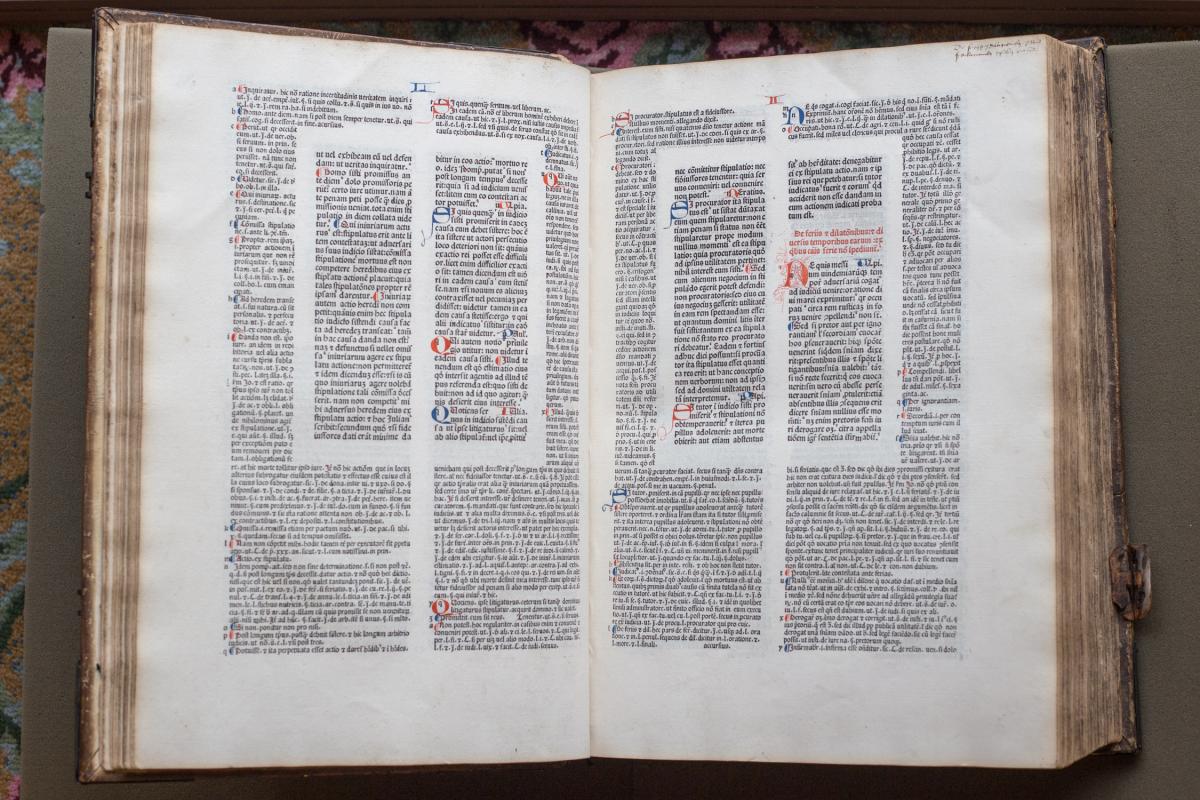

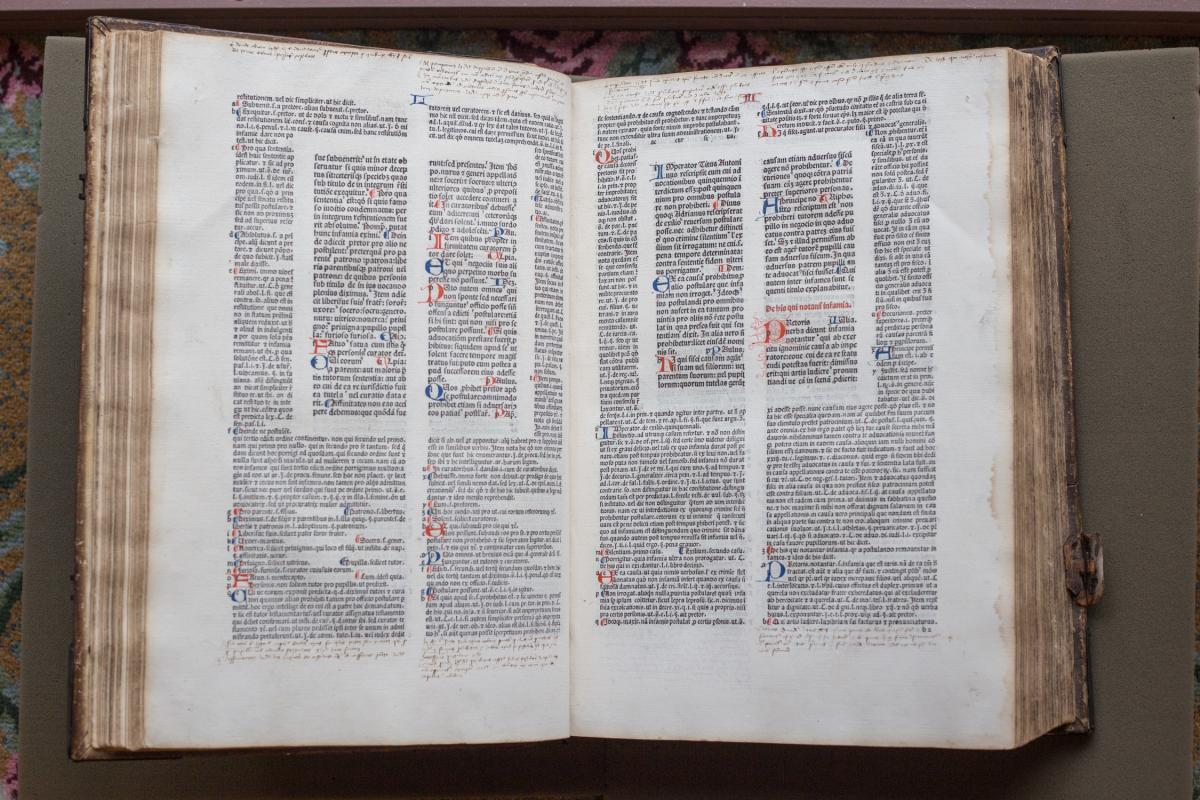

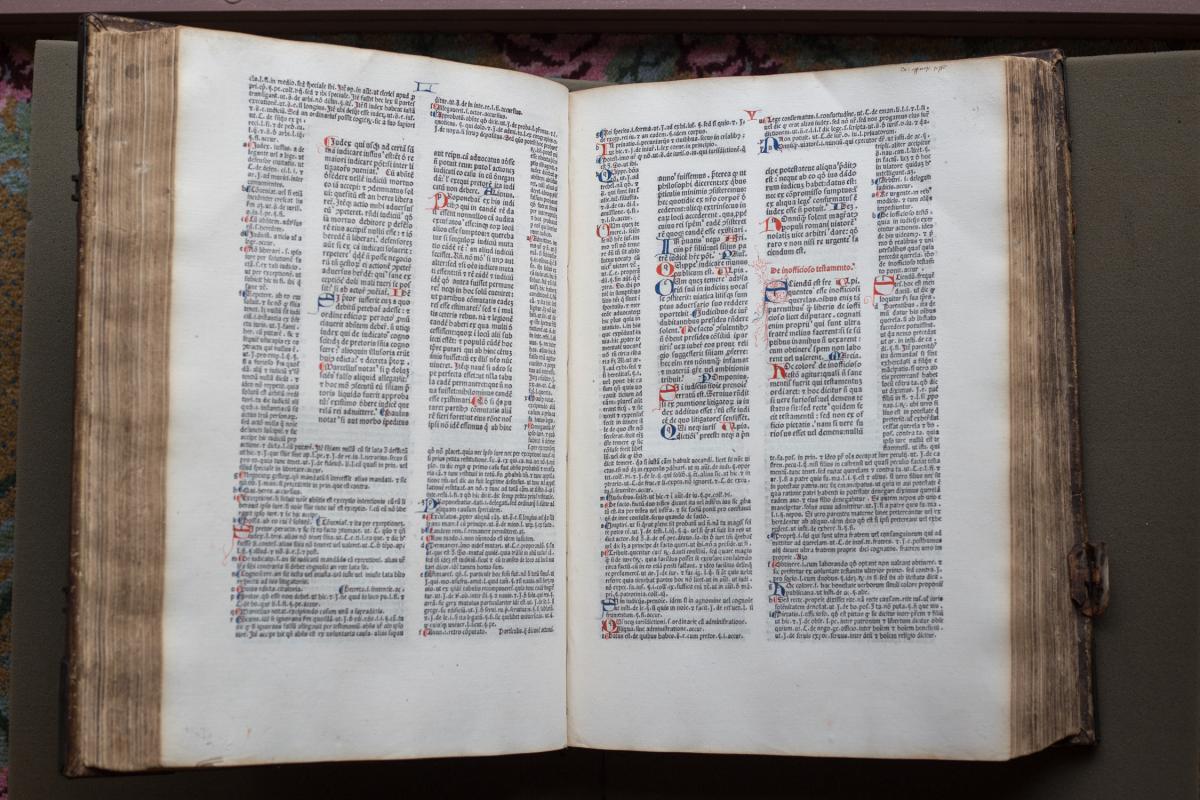

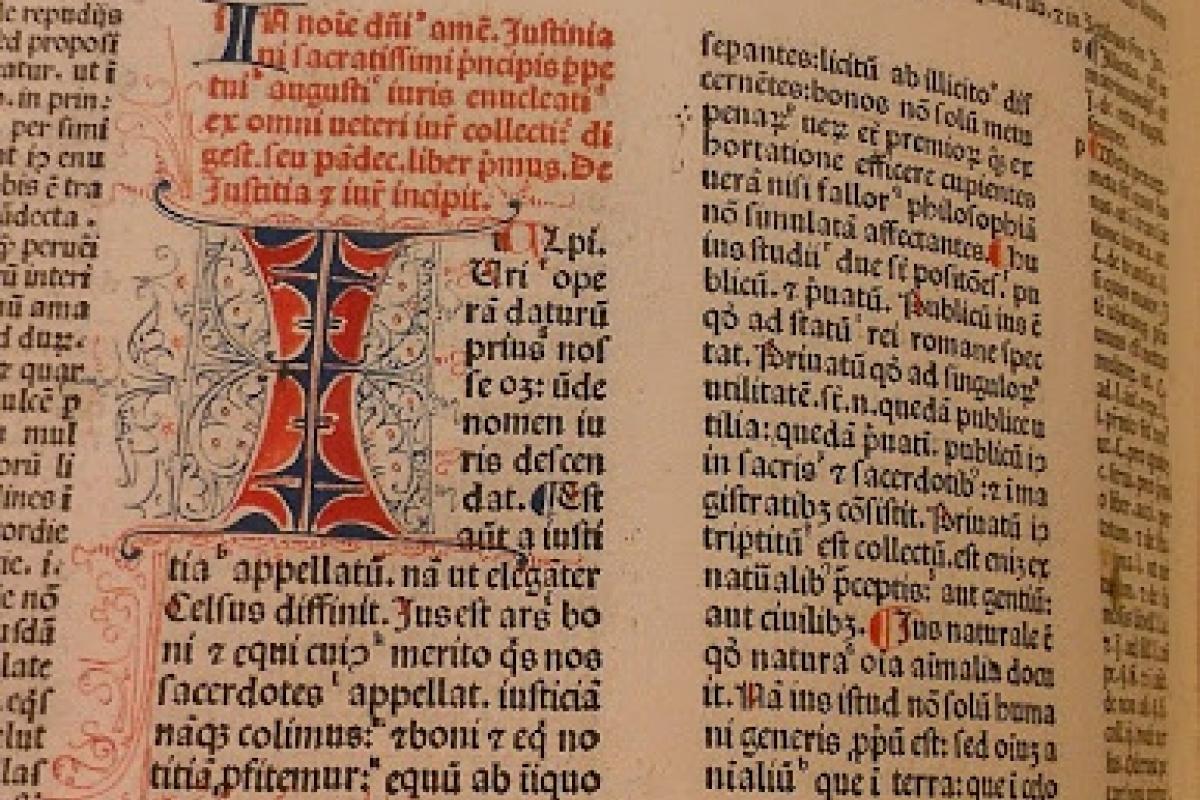

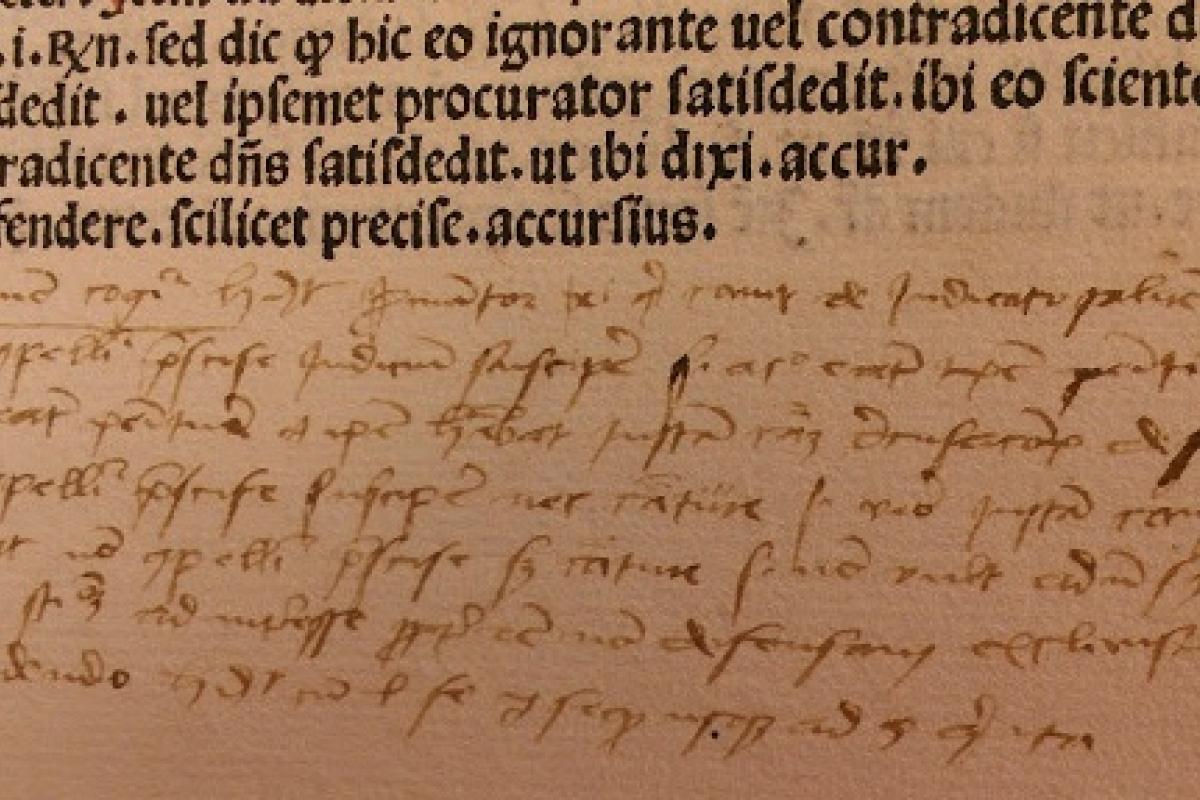

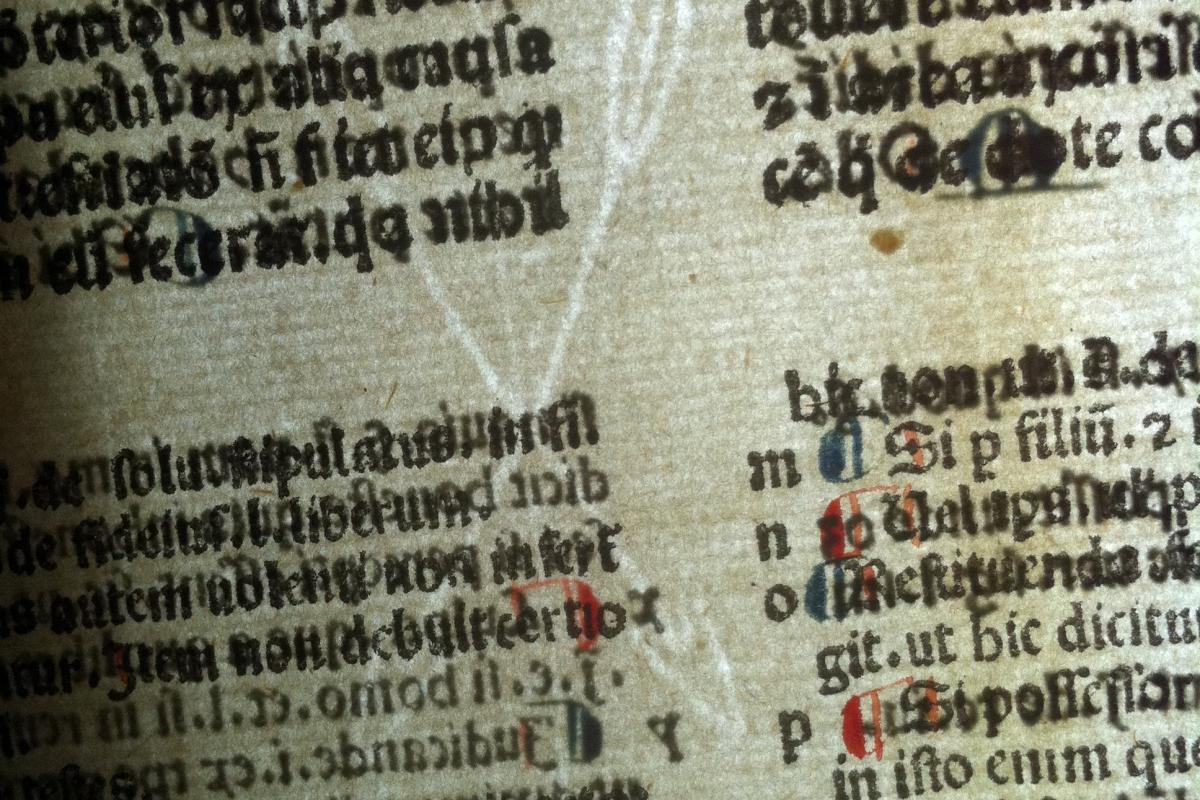

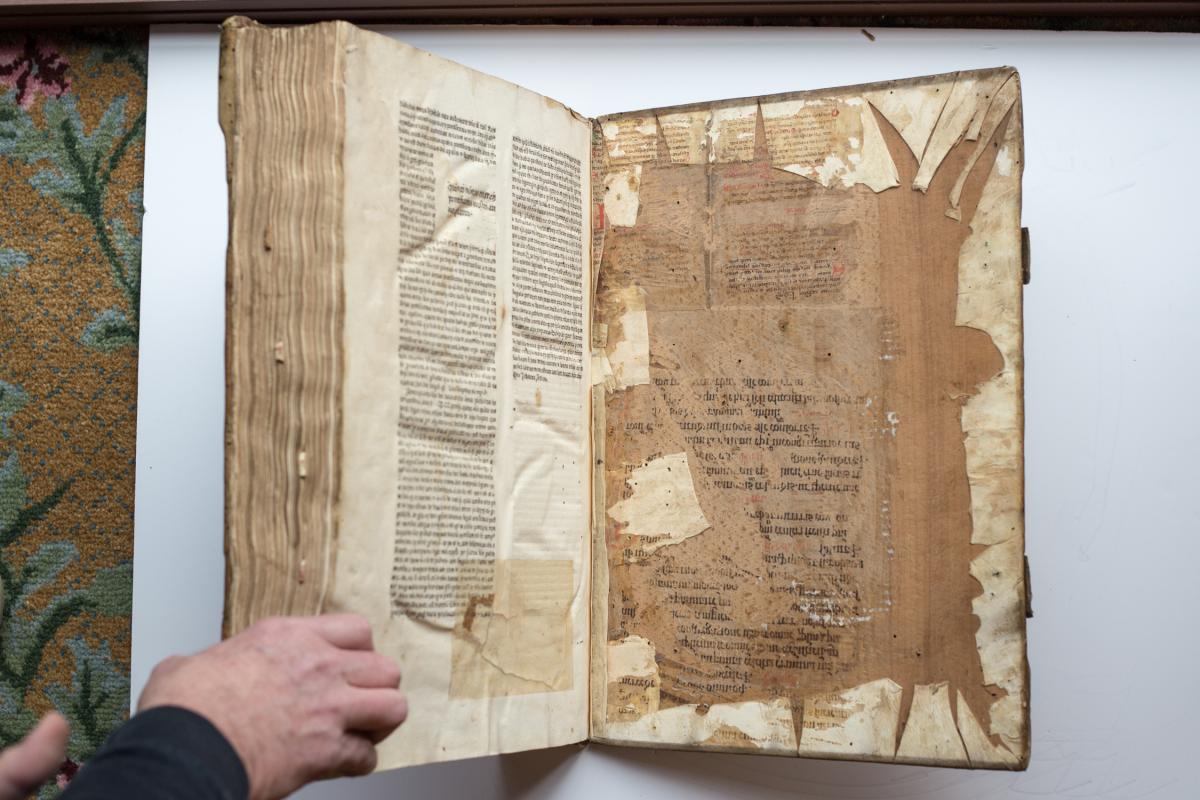

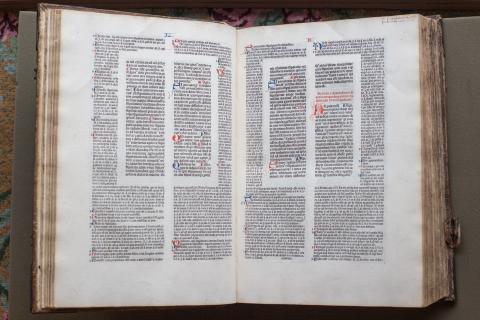

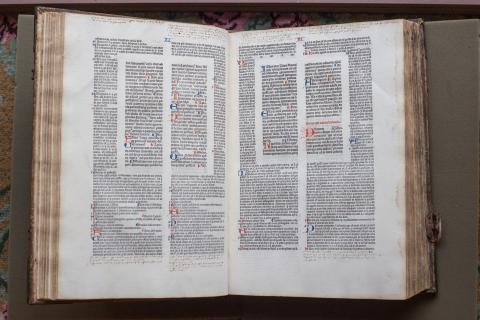

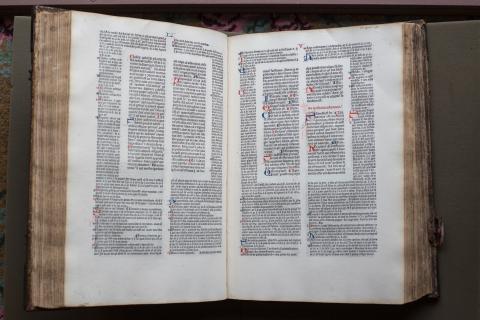

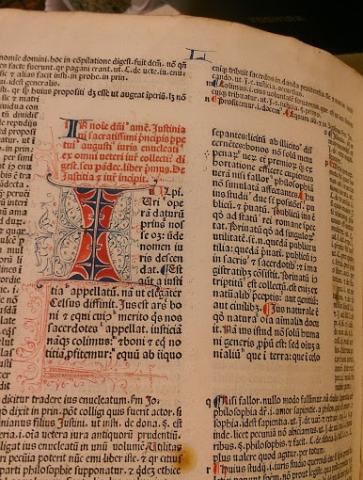

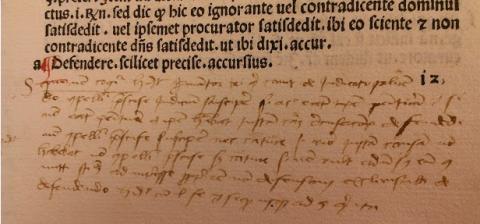

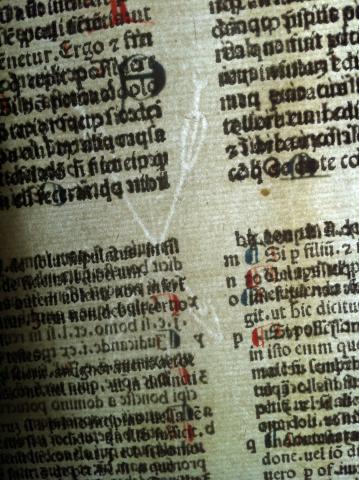

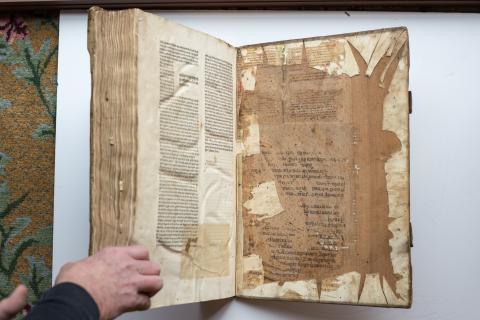

This copy of Justinian's Digest is a fifteenth-century book, printed in two columns, with rubrication throughout in red and blue. There is hand rubrication of single letters and paragraph marks and also printed red text introducing each section. The text is printed on paper and bound in leather over wooden boards. The leather is blind stamped with images of dragons and flowers and retains metal fittings at the corners and center of the cover as well as the remnants of metal clasps, now broken. There is evidence that the metal fittings included raised bosses at one time that are now missing. The leather binding is moderately damaged, primarily at the top of the spine, but the pages have seen only minor water damage around the edges of some pages and occasional wormholes. Regular signature marks were printed in the bottom right of the recto to aid the binder in gathering. There are also handwritten notes in the margins in an abbreviated Latin, presumably penned by a previous owner, along with corrections and nicely drawn manicules.

The first leaf after the introduction appears to be missing. There are three bookplates pasted on the verso of the front endpaper, including one for a Robert Chambers, showing a shield crest and the word "Spero." The vellum endpaper has come unglued from the front board, making visible the construction of the binding and the original color of the leather covering, probably pigskin.

This copy of Justinian's Digest was printed in 1477 in Venice by Jacobus Rubeus, also known as Jacques le Rouge. It is known as the Digestum Vetus, with the Glossa Ordinaria of Accursius.[1] The Digestum Vetus comprises the first twenty-four books of the Digest. Books Twenty-five through Thirty-eight are known as the Digestum Infortiatum, and Books Thirty-nine through Fifty is termed the Digestum Novum.[2] According to records at the British Library, this is one of about thirty extant copies of the Jacobus Rubeus printing of the Vetus. There are also known copies of the Infortiatum printed by Rubeus, but whether he also printed the Novum is unknown. There are known printings of the Novum, however, attributed to Rubeus' contemporary, the printer Nicolas Jenson (one of the most important printers of the period), which were printed in the same city of Venice, and also in the year 1477. Since there is some evidence the two master printers had formed an association around this time, and Rubeus "began to print with Jenson's type in the autumn of 1473,"[3] it is possible they were working together to produce the entire collection of Justinian legal texts. The Digest was one of four parts of the larger work known as the Corpus Juris Civilis (Collection of Civil Law), which was a compilation of Roman law ordered by Emperor Justinian I and directed by Tribonian in the sixth century. The Digest was a compilation of the writings of the ancient jurisconsults who had interpreted the law, and covered all aspects of legal thought from property law to marriage.[4] The other three parts of the Corpus are the Codex, the Institutes, and the Novellae Constitutiones, although the Digest had the most impact on later Western law.[5] There is evidence that Rubeus also did printings of these other sections of the Corpus Juris Civilis.

In the Middle Ages, the Corpus Juris Civilis was taught continuously in the East but lost in the West due to a general decline in literacy, and only rediscovered and studied in western medieval universities around the twelfth century.[6] In this volume, the text of the original Digest is printed in the center of each page in two columns and is surrounded by marginal glosses, many of which are attributed to the thirteenth-century glossator Franciscus Accursius. Accursius compiled a collection of select glosses of the Corpus Juris Civilis, known as the Glossa ordinaria between 1220 and 1250, [7] and these were used in this printing.

At the beginning of each book, within the text, one can find evidence of tabs to help the reader find the first page of each section. The evenly spaced placement of the tabs can easily be seen when looking at the fore-edge of the pages of the closed book. At the top of each recto page is a Roman numeral, in red, indicating the number of the book being viewed on that page. At the top of each verso page is the Roman numeral L, in blue, possibly referring to the total number of books (fifty) comprising the entire Digest, including the Vetus, the Infortiatum, and the Novum.

Periodically throughout the book, one can find watermarks on some of the leaves. The most commonly found watermark appears to be an image of two crossed arrows, but in at least one instance another watermark exists as well, although it is difficult to distinguish.

This beautiful book is significant for myriad reasons. It provides important insights into fifteenth-century printing and bookbinding techniques, it casts light on one of the lesser known master printers of fifteenth-century Venice, Jacobus Rubeus, and it opens a window into the historical interpretation of law during the Middle Ages, and how those interpretations have affected legal thought throughout history and down to our modern world. Much is still waiting to be discovered in its impressive pages.

Notes

[1] Explanations and interpretations of the text made by university scholars were called glosses. Individuals who wrote such glosses were called glossators, and most of these were Italian. See Jonathan Dewald, Ed., "Medieval Roman Law" in Europe 1450 to 1789: Encyclopedia of the Early Modern World (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 2004), 3:465.

[2] William Beloe, Anecdotes of Literature and Scarce Books (London: F. C. & J. Rivington, 1807), 5:30.

[3] Leonardas Vytautas Gerulaitis, Printing and Publishing in Fifteenth-Century Venice (Chicago: American Library Association, 1976), 25.

[4] Kenneth Pennington, "Corpus Iuris Civilis" in Dictionary of the Middle Ages, edited by Joseph R. Strayer (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1983), 3:608.

[5] Alan Watson, Introduction to The Digest of Justinian, edited by Theodor Mommsen and Paul Krueger, and translated by Alan Watson (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1985).

[6] Wolfgang P. Mueller, "The Recovery of Justinian's Digest," Bulletin of Medieval Canon Law 20, (1990): 1.

[7] Dewald, "Medieval Roman Law," 465.

Bibliography

Beloe, William. Anecdotes of Literature and Scarce Books, vol. 5. London: F. C. & J. Rivington, 1807.

Dewald, Jonathan. Ed., "Medieval Roman Law" in Europe 1450 to 1789: Encyclopedia of the Early Modern World, vol. 3. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 2004.

Gerulaitis, Leonardas Vytautas. Printing and Publishing in Fifteenth-Century Venice. Chicago: American Library Association, 1776.

Mueller, Wolfgang P. "The Recovery of Justinian's Digest," Bulletin of Medieval Canon Law 20, (1990): 129.

Pennington, Kenneth. "Corpus Iuris Civilis." In Dictionary of the Middle Ages, vol. 3. Edited by Joseph R. Strayer. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1983.

Watson, Alan. Introduction to The Digest of Justinian, edited by Theodor Mommsen and Paul Krueger, and translated by Alan Watson. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1985.

Keith Rofinot, Medieval Portland Capstone Student, Summer 2005

This fifteenth-century publication of a sixth-century text testifies to the lingering importance of the reforms of the Byzantine Emperor Justinian. The laws in this book are still the basis for legal systems in Europe and even in parts of the U.S.

This large volume has a cover is made of wood which is leather-wrapped with a one-inch turn-in, with metal corner pieces. Stamped on the front of the book are roses and dragons. Two metal clasps on the right side are broken and no longer hold the book shut. When opening the outer cover you will notice there is a split cord with wood pegging, all beautifully intact. The spine is a raised split cord that is also intact. The book is referred to as a tall fifteener. The term "fifteener" refers to the fact that it was produced in the fifteenth century and "tall" refers to the later half of the century. When you open the book you will notice the beautiful Latin text with both large and small illuminations and initial caps. All these illuminations are in red and blue throughout the whole text. Some of the initial caps contain beautiful drawings I also noticed that the style of each page is the same. In regards to the format of the text, each half page is a mirror image of the other. It is thought that Andre Vendramini was the printer.

Emperor Justinian (Flavius Petrus Sabbatius was his name at birth) was born in A.D. 482 in a small village of Tauresium. Justinian's uncle, Justin, a general in the Roman Empire, adopted him. Later Justin became ruler of the Roman Empire and appointed his nephew a senator. In 527 Justinian became co-emperor along with his uncle then the following year became emperor when Justin died. The Byzantine Empire was the cultural hub for all of the Greek, Roman, and Christian areas of the Roman Empire. Therefore Byzantine was the perfect location for Justinian to make a difference throughout the whole Mediterranean.

Justinian's main purpose as the ruler of the Byzantine was to unite the Roman Empire and re-establish the old order. One of the main ways he pursued this goal is mandating the codification of a vast and contradictory corpus of preceding Roman law. In late antiquity, new laws were not properly documented and there were conflicting legal opinions. Tribonian was in charge of gathering all the ancient law books to have all the information from them extracted. The information from those various law books assisted in creating the Corpus Iurus Civilis (The Body of Civil Law). This work was produced in four parts. 1). The Code: a compilation of past codes enacted by other Roman emperors before Justinian's time. 2). The Institutes: made for use by law students of that time and had excerpts from the Code and the last but most important book the Digest. 3). The Digest: composed by a team of about sixteen lawyers and for the first time used the act of past legal cases to enact codes for future individuals. 4). The Novels: codes that were enacted after the corpus was made and were not documented and published until after Justinian's death in 565.