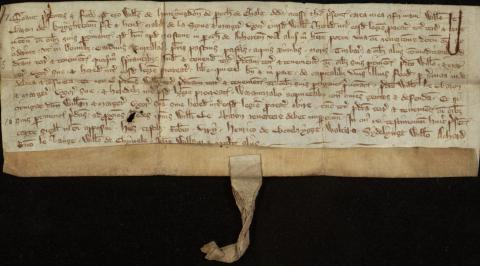

Land Conveyance Regarding Property on the Isle of Wight, England

Land Conveyance Regarding Property on the Isle of Wight, England

English (Isle of Wight), 14th century

Transaction in Isle of Wight, Parish of Chale

Language: Latin

ink on parchment

height 9 cm

width 25 cm

Portland State University Library Special Collections

Mss. 21, Rose-Wright Manuscript Collection no. 13

Jessica Tyner, Medieval Portland Capstone Student, Winter 2005

"In this manuscript, land at Merston on the Isle of Wight changes hands between William le Baron of Knighton and William of Huntingdon (and his wife Margaret) of the parish of Chale"

This land conveyance, written in Latin, has been attributed both to the 14th and the 16th century. The later date seems more credible and was proposed by Dr. Caroline Litzenberger.

During the 14th century, the manorial system dissolved. Since Anglo-Saxon times, the property of the manor was vested in a lord, who held it from the King or from another lord to which services (largely military) were owed (Marriot, 27). The only men who paid for their land monetarily (though often alongside services) were freeholders who constituted 4% of landholders. Upon the dissolution of the manorial system during the 14th century, real estate slowly became a trade. This dissolution has been credited to agriculture and labor conditions which were further troubled by the Bubonic Plague and the Peasant's Revolt (Marriot, 37). The manorial economy was strained due to the severe depopulation caused by the plague which harshly affected the villains (one of a class of feudal serfs who held the legal status of freemen in their dealings with all people except their lord.). This manuscript, which suggests a monetary sale, if written in the 14th century, would likely have been among the first of real estate deals - assuming the Williams were not freeholders.

The 16th century saw agrarian revolution and, via the Act of 1536, the suppression of monasteries and other lesser religious houses. The Reformation was thought by many to be a conspiracy of the rich, and, although it was largely the work of the State, it accentuated the agrarian revolution and is the basis for England's current land system (Brodrick, 30). Lesser religious houses, which may have included parishes, were sometimes sold by the State to men whose only objective was to maximize their financial return. The 16th century also saw the emergence of pauperism. Marriot proposes that the raping of religious houses may have been one of numerous factors that contributed to the new rise of the extreme poor (74).

Other contributing factors to changes in the land system in the 16th century include the "destruction of the old feudal baronage in the Wars of the Roses, the invention of printing, the revival of letters, and the opening of a New World to commerce" (Brodrick, 24).

Early modern England saw the slow progression from oral agreements to written ones in regards to land ownership. Kings and lords giving land in return for services had much less need for written agreements. Written documents were primarily in the King's favor (i.e., the Domesday Book) and often served as a way to track their land and remember what they had. The dissolution of the manorial land system was a slow progression, and the simple features of village societies were still visible under the Henrys and the Edwards. The most central party in determining this fading land system was the parish church (Brodrick, 7). However, with the emergence of a land market, an estate owner began to realize his land was something standing apart from his vassal personality and that land was marketable. Historian D.R. Denman claims that with this realization, "money payments were the acid that wore away the feudal bond and opened the way to the development of a land market" (145).

The Isle of Wight, through all of these changes of the three centuries, endured its own changes. When William the Conqueror became King in the eleventh century, he handed control of the island to a relative. The island was passed down through the generations until finally sold to Edward I in 1293. However, the Crown still did not vie for control of the island, regardless of its vulnerable location - a Duke was named "King of the Island" in 1444 and was crowned by Henry VI. However, as the island's vulnerability to invasion became more evident through increasing French attacks, defensive measures were taken by building fortifications. Attacks from Spain during the 16th century became a worry for the island, and even after the defeat of the Armada, fortifications were strengthened on the island alone out of lingering fear of attack.

The island, prior to the French and Spanish attacks, was a small, close-knit one with the population from the 14th to 16th century ranging from 4,500 to 8,500. It was a favorite vacation spot for royalty and saw a few firsts for England, such as the first recorded windmill and the first printing of Chaucer's Canterbury Tales. During the 16th century, the island population dwindled and religious dwellings fell into decay. Had the manuscript in question been written during this time, it would leave one wondering the purpose behind the acquisition of a parish in an area that had lost interest in preserving the parishes.

Suggestions for further reading:

Books

- Brodrick, George C. English Land and English Landlords. New York: Augustus M.

- Kelley Publishers,1968.

- Denman, D.R. Origins of Ownership. London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd.,1958.

- Marriot, J.A.R. The English Land System. London: John Murray, Albemarle Street, 1914.

Websites

- The Isle of Wight. http://www.genuki.org.uk/big/eng/HAM/IOW/. February 27, 2005.

- Welcome to Chale. http://www.chale.org.uk/. February 27, 2005.