Oaks Pioneer Church

Oaks Pioneer Church (St. John’s Evangelical Episcopal Church)

1852

455 SE Spokane Street, Portland, Oregon

Heidi Shewchuk, Medieval Portland Capstone Student, 2020

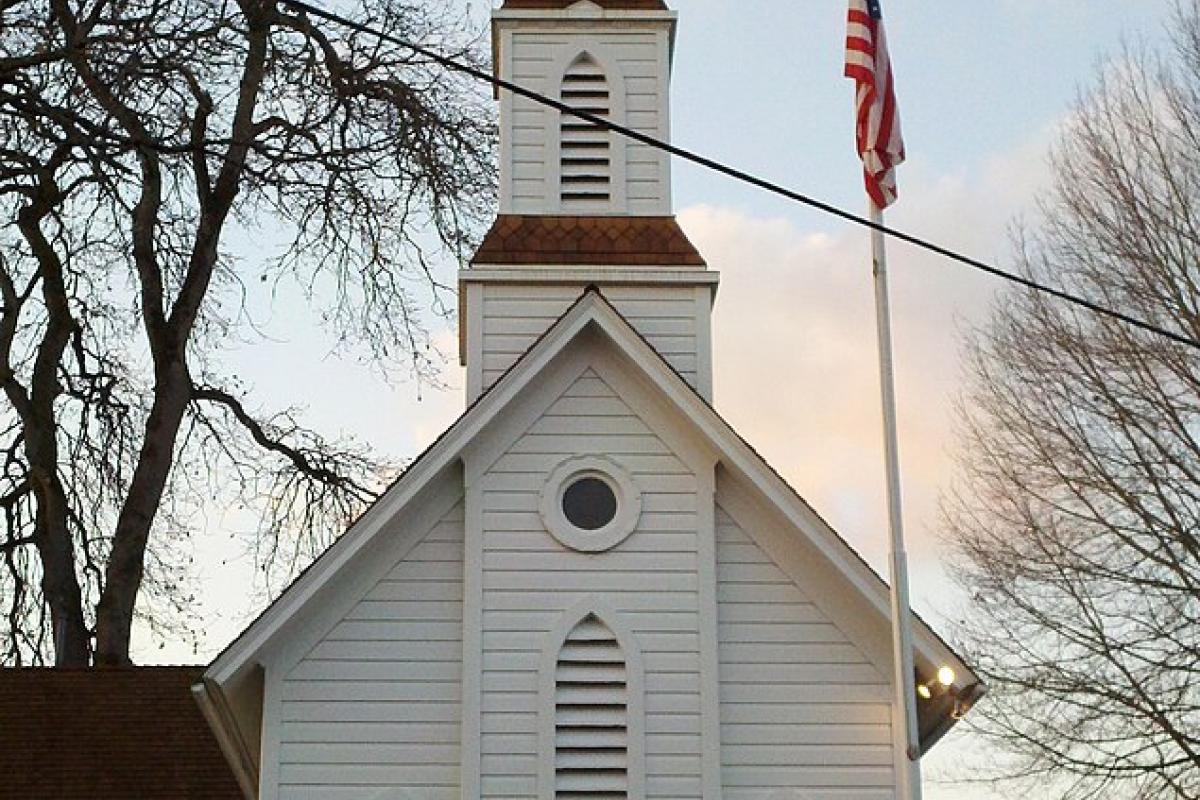

At first glance the wooden Oaks Pioneer Church seems like a classic 19th-century Carpenter Gothic church with its belfry, tall pointed steeple, and lancet windows. But it has not always stood at this location, nor was it initially constructed as a Carpenter Gothic church. The structure was originally built in 1851 by Lot Whitcomb for use as a modest, two-family home. It stood at the edge of Milwaukie, Oregon, the town Whitcomb had founded. Whitcomb donated the unfinished house along with two parcels of land to Milwaukie’s newly formed Protestant Episcopalian congregation for use as their church. They named their new church St. John’s Evangelical Episcopal, and construction on the building was finished in February 1852. The church was a simple rectangular structure, built using heavy post and frame construction, utilizing locally milled timbers that were notched with mortise and tenon connecting joints and secured together with wooden pegs. It was fitted with double-hung square windows, the outside sheathed in shiplap siding, and possessed a rudimentary belfry, but no tower, or spire.

Over the next thirty-six years, various improvements and enlargements were made to St. John’s church, but its façade and interior remained unchanged until the renovations undertaken by Rev. Thomas Sellwood in 1888. This was when the church was given its “Gothification,” with the addition of lancet-shaped windows, a three-paneled stained-glass chancel window in the rear wall above the altar, and a tower with lancet-shaped louvers, and a round rose window with clear glass. This was surmounted by a four-sided spire atop a square belfry, and a vestibule was also added to the entrance. The old siding was also replaced with new horizontal drop siding, and the church was given a new, higher-pitched roof. The interior underwent a dramatic remodel with the installation of tongue and groove paneling made up of 4” wide fir boards laid diagonally in a chevron pattern across the walls and ceiling. A report written by Rev. Sellwood in the 1889 Journal of the Primary Convention, states that the renovations occurred in the winter of 1888, and were completed on March 31, 1889, when the church reopened.

With the completion of these renovations, the church now appeared to be a purpose-built Carpenter Gothic Church, a style popular at the time it was constructed. The Gothic Revival vernacular had been brought into the Oregon territory by 1840, and pattern books containing plans for wooden Carpenter Gothic churches were available in 1852. At the time St. John’s was finished, ecclesiastic Gothic Revival architecture was the dominant style used by the Episcopal church in North America, because it was seen as the most appropriate for Episcopalian church architecture. This association began in the late 18th century when the early American Episcopalian church used Gothic Revival vernacular to differentiate it from other Protestant denominations who built their churches in the neoclassical style. But, beginning in 1840, it was the influence of the English Cambridge Camden Society, a group of reform-minded architectural theorists, or “ecclesiologists,” that firmly established Gothic Revival as the correct form for Episcopalian churches. They believed that Medieval, or Gothic architecture embodied the sacred doctrines of Christianity, and no other style was as effective at fostering a constructive social influence on its parishioners. By the end of the nineteenth century, ecclesiastic Gothic Revival architecture was linked directly to a broader and unifying sense of American Protestant Christian doctrine, and identity. This led to many churches originally built in the Georgian, or neoclassical style, being given a Gothic Revival makeover in order to align themselves with this doctrine. Gothic Revival was also adopted by other Protestant denominations simply because it was seen as a uniquely Christian and desirable church form. Two examples of “Gothified” churches are Trinity Episcopal Saint Mary’s Chapel, located in Saint Mary’s City, Maryland. It was rebuilt in 1889 from a two-story Georgian structure into a one-story, brick chapel in the style of a wooden Carpenter Gothic church. The other is the Unitarian Church in Charleston, North Carolina, remodeled in 1852 by architect Francis D. Lee from the Georgian vernacular into the Perpendicular Gothic Revival style.

After 109 years of service, St. John’s was decommissioned in 1961 and moved by barge down the Willamette River to its present location and renamed The Oaks Pioneer Church. It was restored by the Sellwood-Moreland Improvement League, and it currently serves as a nondenominational chapel and popular wedding and event venue.

Sources

Beck, Dana. “Southeast History- in its third century Oaks Pioneer Church,” The Bee, April 3rd, 2020.

Carter, Liz. Pioneer Houses and Homesteads of the Willamette Valley, Oregon 1841-1865. Historic Preservation League of Oregon, http://restoreoregon.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/Pioneer-Houses-and-Homesteads_web.pdf. 21-2, accessed April 27, 2020.

Cropsy, Heidi. “History of The Oaks Pioneer Church.” The Oaks Pioneer Church, https://oakspioneerchurch.org/history-of-oaks-pioneer-church/

Episcopal Church. 1889. Journal of the Primary Convention of the annual Convention of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the Diocese of Oregon, Held in TrinityChurch Portland, Sept. 11th,12th,13th, 1889. Accessed May13,2020. https://play.google.com/store/books/details?id=u-cQAAAAIAAJ&hl=en.30

Kilde, Jeanne Halgren. "Formalism and the Gothic Revival Among Evangelical Protestants." In When Church Became Theatre: The Transformation of Evangelical Architecture and Worship in Nineteenth-Century America, New York: Oxford University Press, 2002.

Kocyba, Kate M. “Identity through Style: The Transatlantic Dissemination of Anglican and Episcopalian Neo-Gothic Church Architecture." Dissertation. No. 13869921, University of Missouri - Columbia, 2012.

Olson, Charles Oluf. Federal Writers' Project, and Milwaukie Historical Society. History of Milwaukee, Oregon, 1965,https://ir.library.oregonstate.edu/concern/defaults/bc386k46p?locale=en, 69

Powers, D.W. St. John’s Episcopal Church, National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form, 5 August 1974. Identifier Number 77850991. Department of The Interior, National Parks Service, National Archives Catalog. National Archives at College Park, College Park Maryland. http://catalog.archives.gov/id/77850991.2.

Sobon, Jack A. Historic American Timber Joinery, a Graphic Guide. 2nd printing. Becket, MA: The Timber Framers Guild, 2004.

Stanton, Phoebe B. "The Gothic Revival & American Church Architecture; an Episode in Taste, 1840-1856." Johns Hopkins Studies in Nineteenth-century Architecture. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1968.

Stein, Carol. St. John the Evangelist Episcopal Church, A Place in History, 1851-2001. Privately printed booklet on the occasion of the church's 150th Anniversary. Milwaukie, Oregon: St. John the Evangelist Episcopal Church, 2001.

Upjohn, Richard. Upjohn’s Rural Architecture: Designs, Working Drawings and Specifications for a Wooden Church, and Other Rural Structures. G.P. Putnam, 1852.

Webster, Christopher. "Cambridge Camden Society, Ecclesiological Society (act. 1839–1868)." Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. 19 May, 2011.

White, James Floyd. The Cambridge Movement: The Ecclesiologists and the Gothic Revival. 2nd edition. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 1979.

Whytock, Jack C. "Carpenter Gothic," in The Encyclopedia of Christian Civilization, Edited by George Thomas Kurian. New Jersey, United States: Blackwell Publishing Ltd., 2011.