Bible

Bible

French, 13th century

Language: Latin

height 15.8 cm

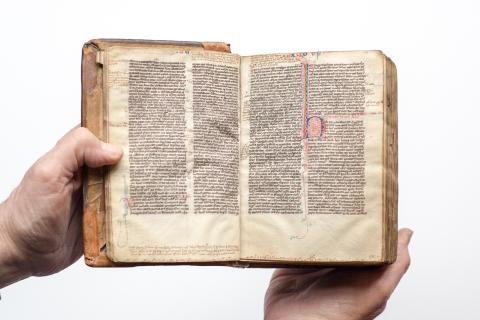

width 11.5 cm

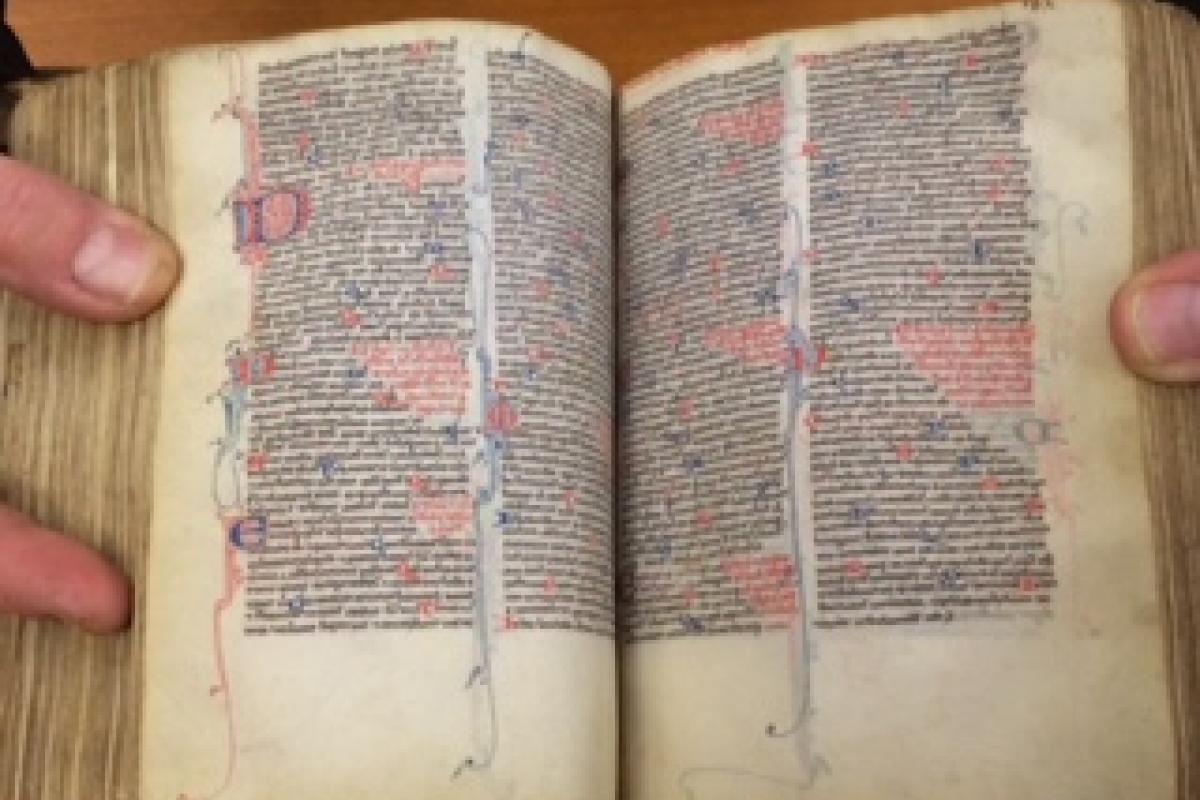

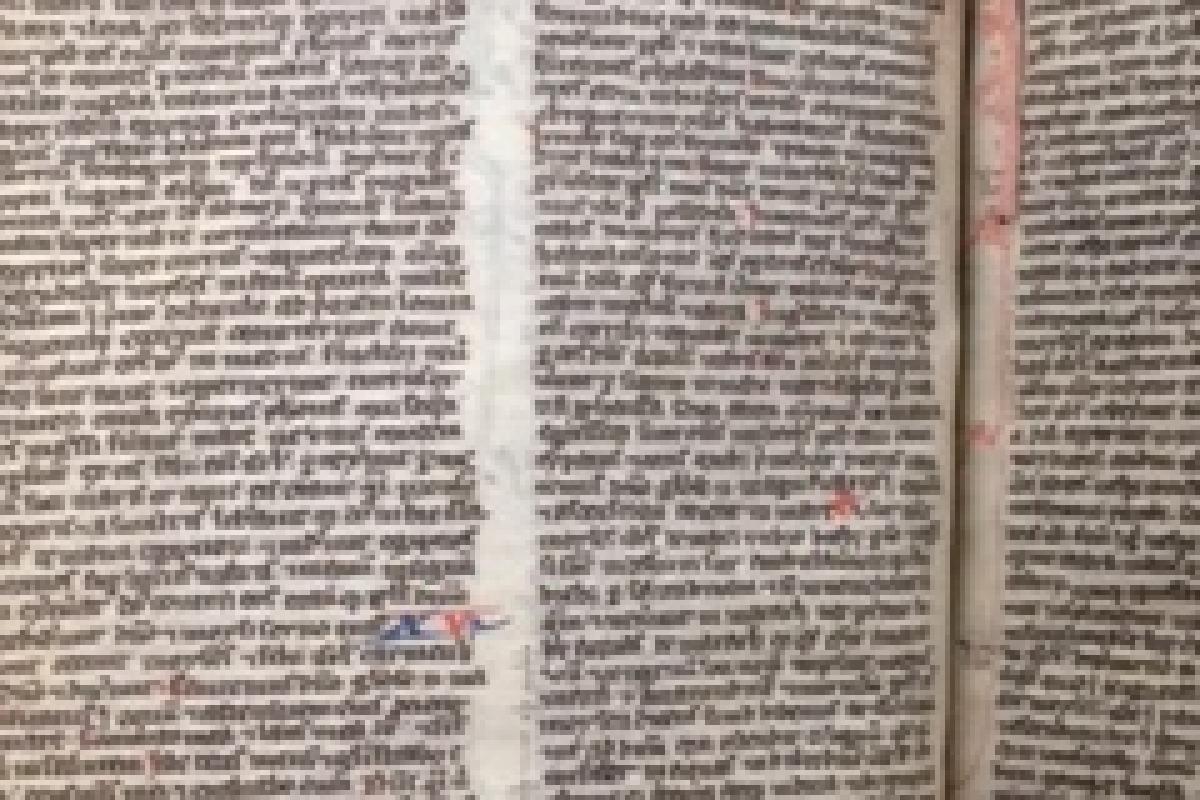

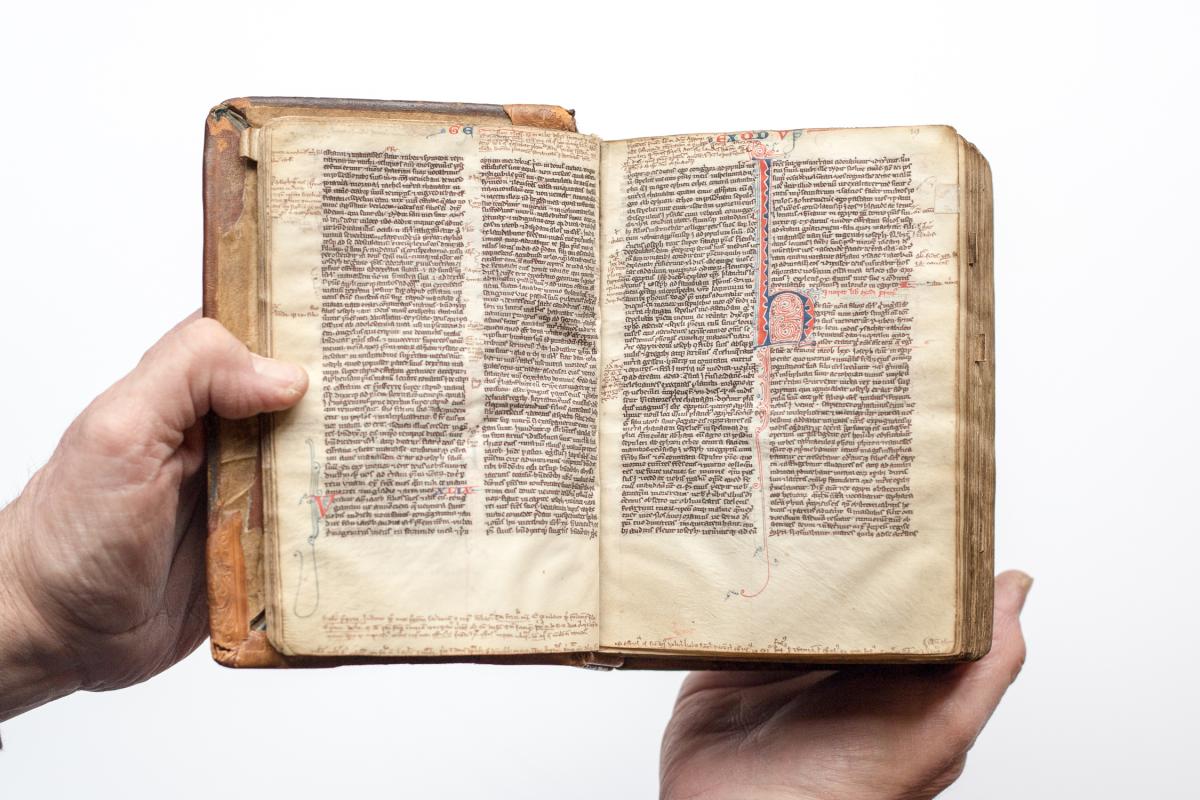

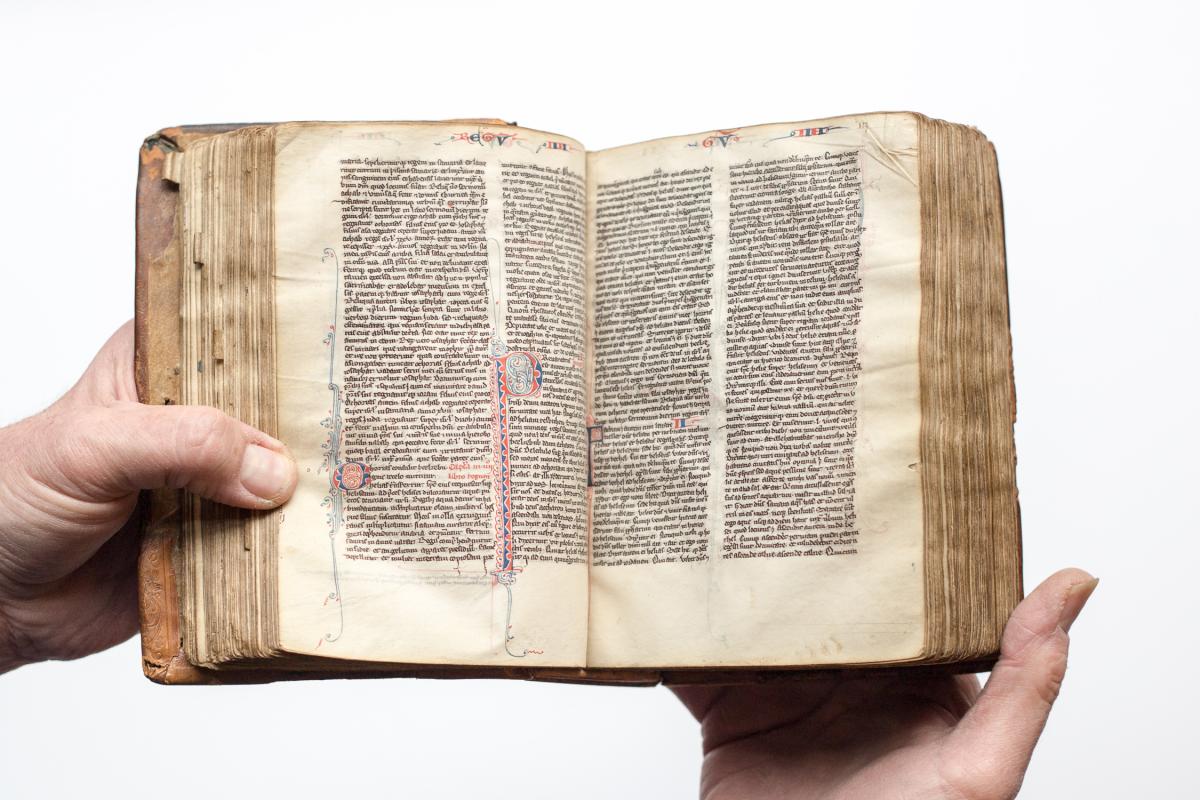

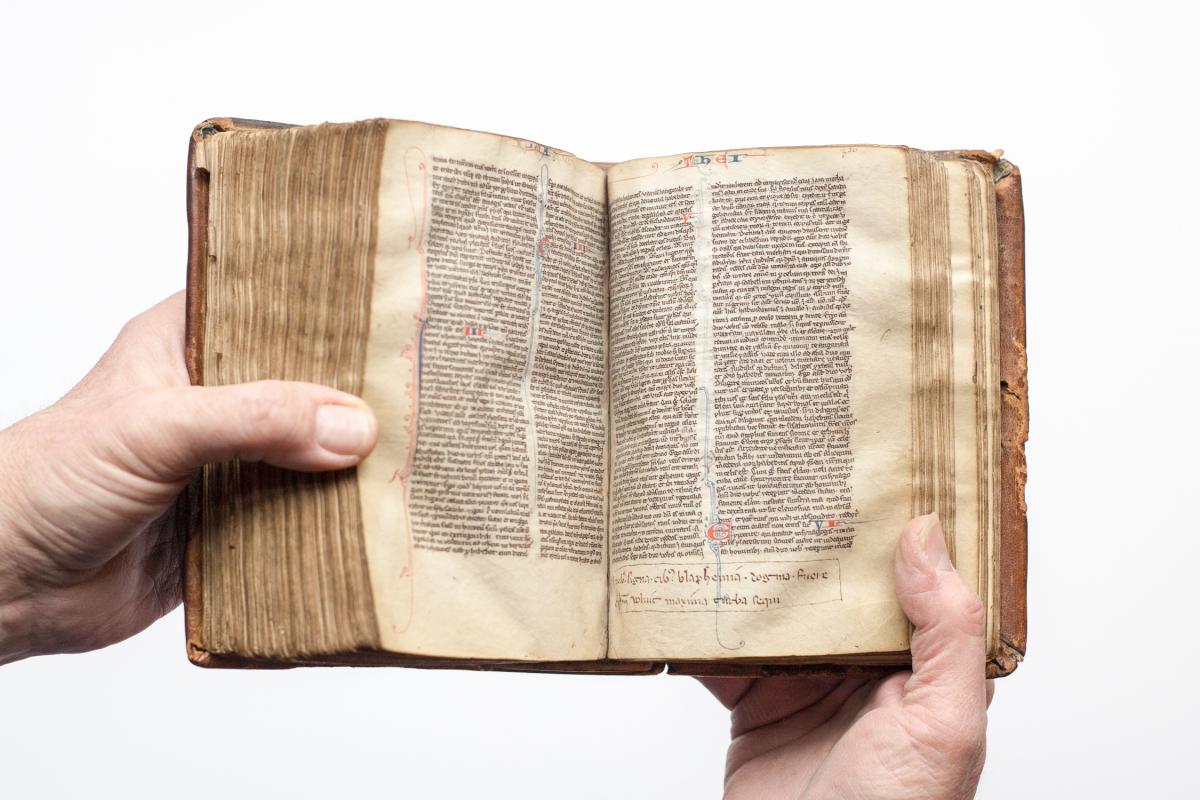

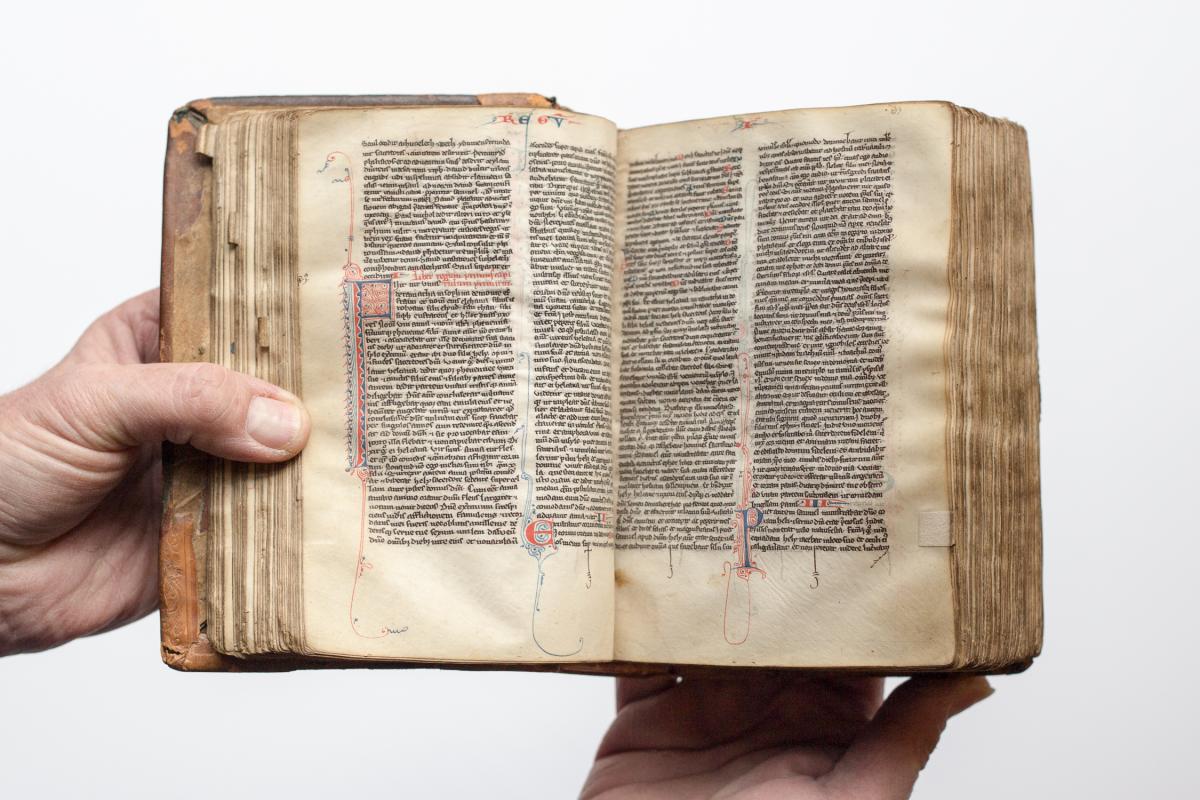

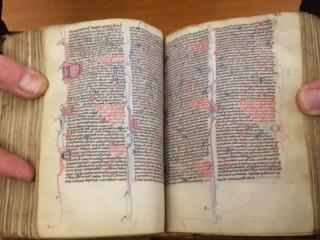

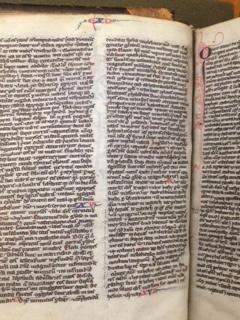

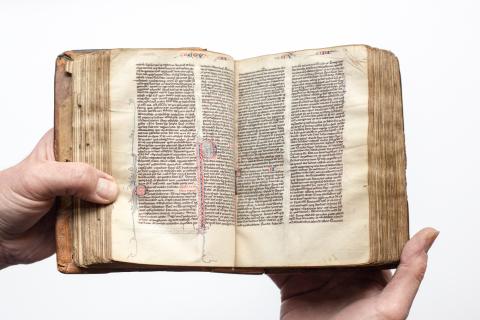

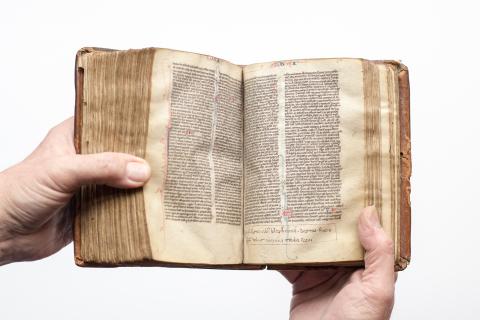

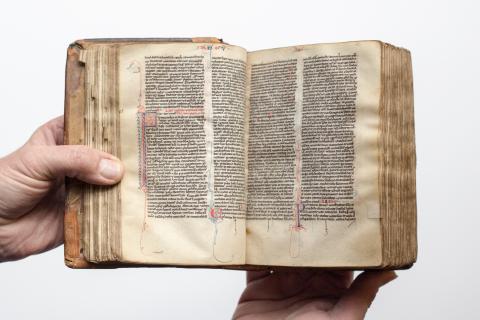

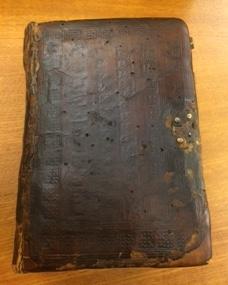

437 leaves. Small square Gothic script. 51 lines in 2 columns. Text in Latin: Vulgate edition with St. Jerome's prologue. Many decorated initials in red and blue with elaborate penwork in the margins. Binding: brown calf with blind stamping, 14th-15th c.

Provenance and Prior Publication:

The bookplate of Reverend W.H. Pengelley, MA is on the back, inside cover. Publications: Parshall 2, p. 10 and Seymour De Ricci, with the assistance of W. J. Wilson, Census of Medieval and Renaissance

Multnomah County Library Catalog Info: W091 B582 Asc. No 8083-31168045410212

Parshall, Peter. Illuminated Manuscripts from Portland Area Collections. Portland, OR: Portland Art Museum, 1978, p. 10 - Quoted with permission

During the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, Paris emerged as a major center of manuscript production. As the demand for books increased, commercial scriptoria and purveyors of manuscripts began to cluster in the University district of central Paris. Despite indications of mass-production techniques employed to meet a growing lay and clerical readership, works from this period still evidence the delicacy and personal distinctiveness we associate with the hand-made book and its longstanding tradition. This manuscript is one of many so-called "pocket Bibles" done in a minute script sufficient to include the complete text in one manageable volume. The vellum is of high quality, thin and uniform throughout. Intricately scalloped initials and delicate penwork establish an active interrelation of text and decoration that lends its pages a playful, filigreed elegance typical of the late Gothic aesthetic.

Provenance: Rev. W.H. Pengelley (ex libris); H. Southeran & Co., London; John Wilson (ex libris).

Wilma Fitzgerald, PhD, SP - Quoted with permission from an unpublished study

Vetus et Novum Testamentum cum prologo Sancti Hieronymi et Interpretationes nominum hebraicorum Bibliae. Saec. XIV ex. FF. 1 + 400., 160 x 108 (115 x 90), two columns., 51 lines. Headings blue, red with ascenders and descenders. Bound in old leather tooled with repeat decoration on wooden boards (70 x 115 spine 60 mm.). Clasp binding from front to back is missing. Some tabs remain. Purchased by John Wilson from H. Southeran and Co. Catalogue 5 # 559 November 1896. Wilson's book plate i fly leaf. On back board the book plate of Rev. W. H. Pengelly MA. His coat of arms with motto: Prospicio non despicio. (Library acc. # 8083).

f. 394. Interpretationes nominum hebraicorum bibliae: [Aa]z aprehendens apprehensio uel destificans uel destimonium [ad testificans uel testimonium] [ending mut. without ornamentation without capital letters.]

f. 400. Interpretationes nominum hebraicorum bibliae: Aaz aprehendens apprehensio uel destificans uel destimonium [ad testificans uel testimonium] [Initials more elaborate than in Bible. Not part of original work]

Rebecca Mazzio, Medieval Portland Capstone Student, Summer 2005

The Bible is undoubtedly one of the most important books in western history. During the 13th century, its use increased, as manuscripts became smaller and more portable. The Biblical text became more uniform through a new focus on accuracy. Medieval Bibles helped shape modern biblical text and form. The oldest manuscript in the John Wilson Room, in the Multnomah County Library, is a Bible, dated 1250. It is from an unknown location but seems to show many characteristics of a French manuscript. It also seems to have been made for a monk, though the description claims it was a student copy. The Wilson Room Bible was not unique in its time but should be considered a treasured item today. It represents changes in religion and spiritual understanding while pre-dating technology like the printing press. It is a truly amazing manuscript.

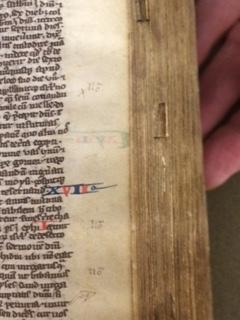

The materials used to make the Wilson Room Bible were very standard. The pages are made of vellum and are rather small. In many vellum manuscripts, which are roughly 4 by 5.5 inches, the skin has been folded 5 times, making 32 pages [1]. This size is in many ways optimal for personal use, it makes the book small enough to carry, but large enough to write in and read. The book moreover was longer than it was wide, which is standard for books today. Animal skin is naturally oblong, which is why the pages took this shape [2]. The binding on the book is leather, and it would have had straps to hold the book closed since vellum can expand and warp over time. These straps are gone, but the remains are there in the form of exposed metal pieces on the center right edge of the front of the book.

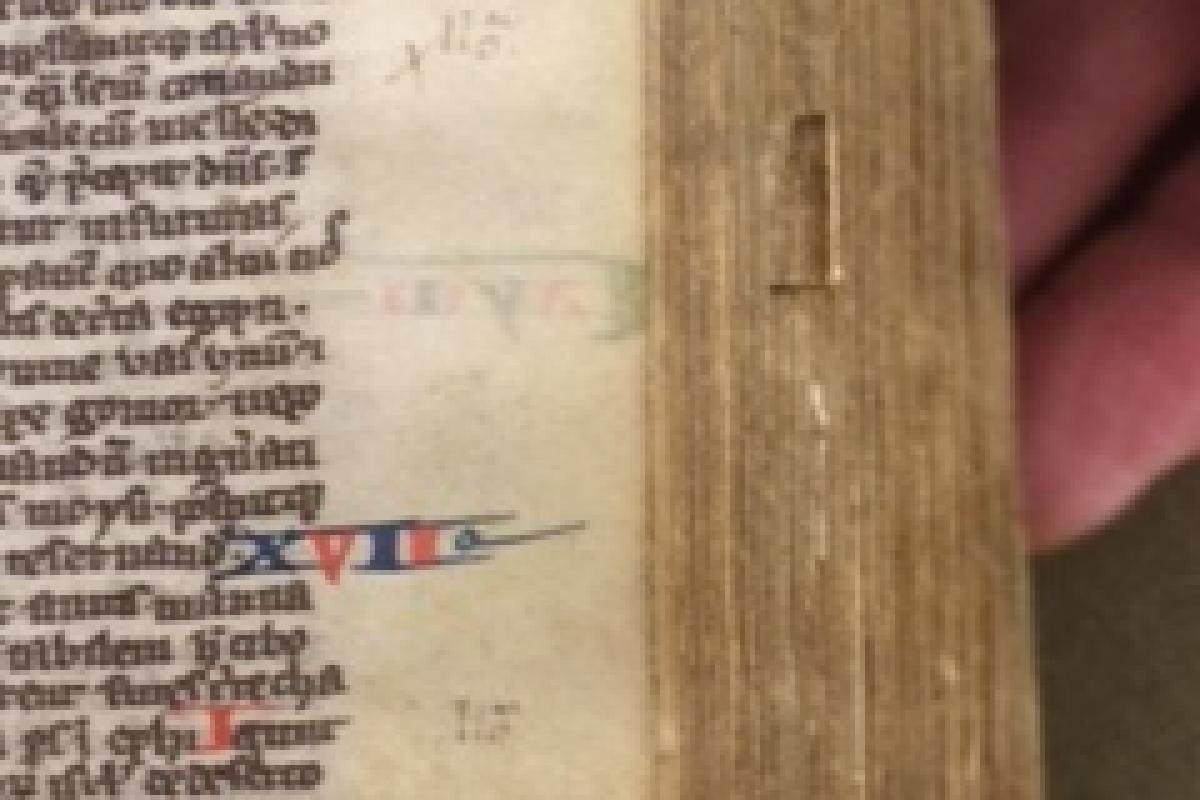

The development and production of the medieval Bible were further improved by the growth of the university and mendicant orders, such as the Dominicans and the Franciscans. As more students and monks required texts, more were produced. Bibles for monks often had easily usable features, such as tabs in the chapters, numbered verses, red and blue foliation, and titles that spanned opposite pages [3]. These characteristics are all present in the Wilson Room bible. The production of these books was overseen by one person and passed through several hands before they were complete. As texts became more widely needed, copying became faster. By outsourcing different sections to different scribes books could be made quicker, and more copiers could have jobs. This allowed the text to be finished quickly and inexpensively.

The portability of the Bible was also essential, especially to Franciscans and Dominicans. These groups both gained followings in France during the early to mid-thirteenth century and competed somewhat in their ability to spread the gospel. Often they required texts easy to carry because of their travels. Before this necessity of convenience, Bibles were often produced in pieces, different sections being entirely different books. In the late twelfth and early thirteenth century, the Bible began to be compiled into one text. It was divided into chapters and written in two columns per page. Many also contained the Interpretation of Hebrew Names, which was an alphabetical listing of the Latin meanings of Hebrew names [4]. These characteristics are present in the Wilson Room Bible. This change was very significant. Bibles today still follow this basic outline, they are even written on thin paper, mimicking vellum. Bibles written in the mid-thirteenth century were used for decades, even centuries. They were made so well that families often passed them down. Standardization and accuracy also became increasingly important. The Dominicans especially valued accuracy, as they sought to avoid heresy, and biblical scholarship was at the heart of their order [5].

Latin was the language of the church and scholars, making it the language of the Bible. The Vulgate was the standard translation of the biblical text, which is based on the Hebrew scriptures that makes up the Old Testament. The Vulgate was again revised in the 9th century and named the Clementine Vulgate [6]. This version was widely used in Europe and most likely is the translation used in the Wilson Room Bible. The Catholic Church recently adopted a new official Latin text called the Nova Vulgata.

One of the most unique and interesting parts of medieval manuscripts is the beautiful decoration of pages known as illumination. The Wilson Room bible has some illumination, primarily in red and blue. Flourishing, is also present, though minimal. As mentioned previously, the ornamentation of Bibles helped the reader navigate the text easily. The Wilson Room bible has both illuminations on each book within the bible, and also illumination that divides chapters. The illumination in each book of the text highlights the first letter. These illuminations can be simple as is the case of the Wilson Room bible, or they can be painstakingly intricate, embellished with gold leaf and rare inks. The illumination throughout the Wilson Room Bible is primarily that of chapter divisions. Each first letter of almost every chapter is decorated with red ink primarily. Some examples remain of red ink being used in medieval bibles to write the word of God, which also is present to a limited degree in the Wilson Room Bible. This is most likely connected to the modern-day practice of highlighting God's word in the bible in red. As the text progresses in the Wilson Room Bible, the illumination becomes less ornate. The index of Latin name translations is also illuminated at each letter of the alphabet.

The Wilson Room Bible also includes the title of each book within the Bible written across the top of each page. It is written completely on the first page of the book and then broken up so that half is on one page and half on the other when a book is open and flat. Examples of this can be seen in many medieval manuscripts, not just the bible. John Wilson, the donor of the Wilson Room Bible, also left his own mark on the medieval text, by drawing small hands, faces, and notes in the margins. These are not medieval drawings because they all seem to be in pencil and are on several other manuscripts that he donated to the collection. As mentioned before, Dominicans developed in France Bibles similar to the Wilson Rare Book Room, because they traveled and needed to be able to keep the biblical text with them. On one of the inside pages of the Wilson Room Bible, there is a note claiming the bible is from France, and that it dates from 1371. I tend to agree with the Wilson date, which places the text at 1250, but agree with the previous owner's note, that the bible is French. The connection between the Dominican friars, the details in the text, tabs on the chapters, and time frame all seem to match this attribution.

Notes:

[1] Christopher De Hamel, A History of Illuminated Documents. (New York: Phaidon Press, 1986), 89.

[2] De Hamel, 89.

[3] Rowan Watson, Illuminated Manuscripts and Their Makers, (London: V&A Publishers, 2003), 69.

[4] De Hamel, 118.

[5] De Hamel, 123.

[6] Catholic Online, Catholic Online Saints: St. Jerome Doctor of the Church. http://www.catholic.org/saints/saint.php?saint_id=10

Suggestions for further reading:

- De Hamel, Christopher. A History of Illuminated Manuscripts. London: Phaidon Press, 1986.

- Herren, Michael W., McDonough, C.J. and Arthur, Ross G. ed. Latin Culture in the Eleventh Century. Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols Publishers, 1998.

- Murdoch, Brian. The Medieval Popular Bible: Expansions of Genesis in the Middle Ages. Cambridge: D.S. Brewer, 2003.

- Sharpe, Richard. Identifying Medieval Latin Texts: An Evidence Based Approach. Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols, 2003.

- Smith, Julia M.H. ed. Early Medieval Rome and the Christian West. Brill, Netherlands: Koninklijke, 2000.

- Stelten, Leo F. Dictionary of Ecclesiastical Latin. Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers, 1995.

- Watson, Rowan. Illuminated Manuscripts and Their Makers. London: V&A Publications, 2003.

- Weiss, Daniel, and Mahoney, Lisa. France and the Holy Land: Frankish Culture at the End of the Crusades. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004.

- Williams, John, ed. Imaging the Early Medieval Bible. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1999.