Carta Ejecutoria: Leaf from a Grant of Arms to Juan and Alvaro Fernandes del Rincon

Carta Ejecutoria

Leaf from a Grant of Arms to Juan and Alvaro Fernandes del Rincon

Spanish, 1630 (?)

height 31 cm

width 22 cm

Portland State University Library Special Collections

Mss. 26, Rose-Wright Manuscript Collection no. 18

Jacob Sherman, Medieval Portland capstone student, 2008

Portland State University's Library holds a well-preserved manuscript in its Rose-Wright Collection, providing a unique glimpse at early modern Spain's cultural history. Entitled, "Leaf from a grant of arms to Juan and Alvaro Fernandes del Rincon," this single folio, of what was once a longer document,[1] traces the legal pursuit of nobility by the two brothers, Juan and Alvaro Fernandes del Rincon.

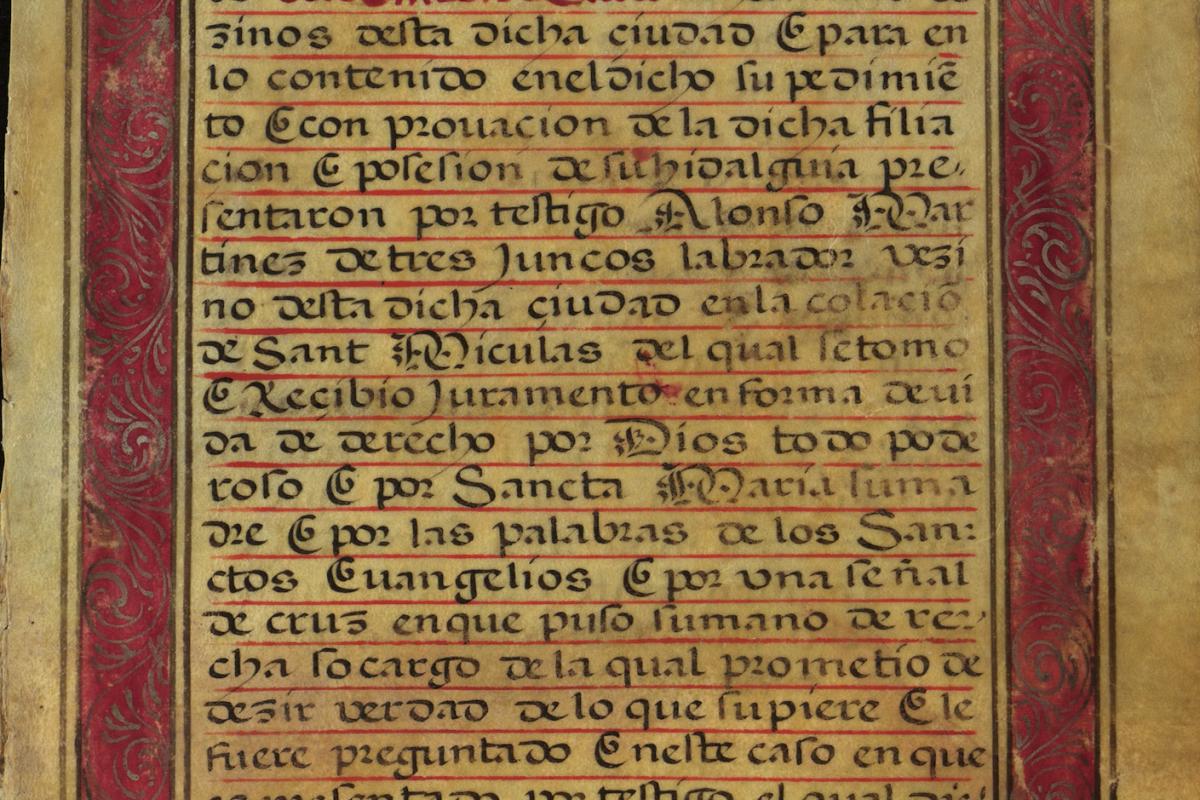

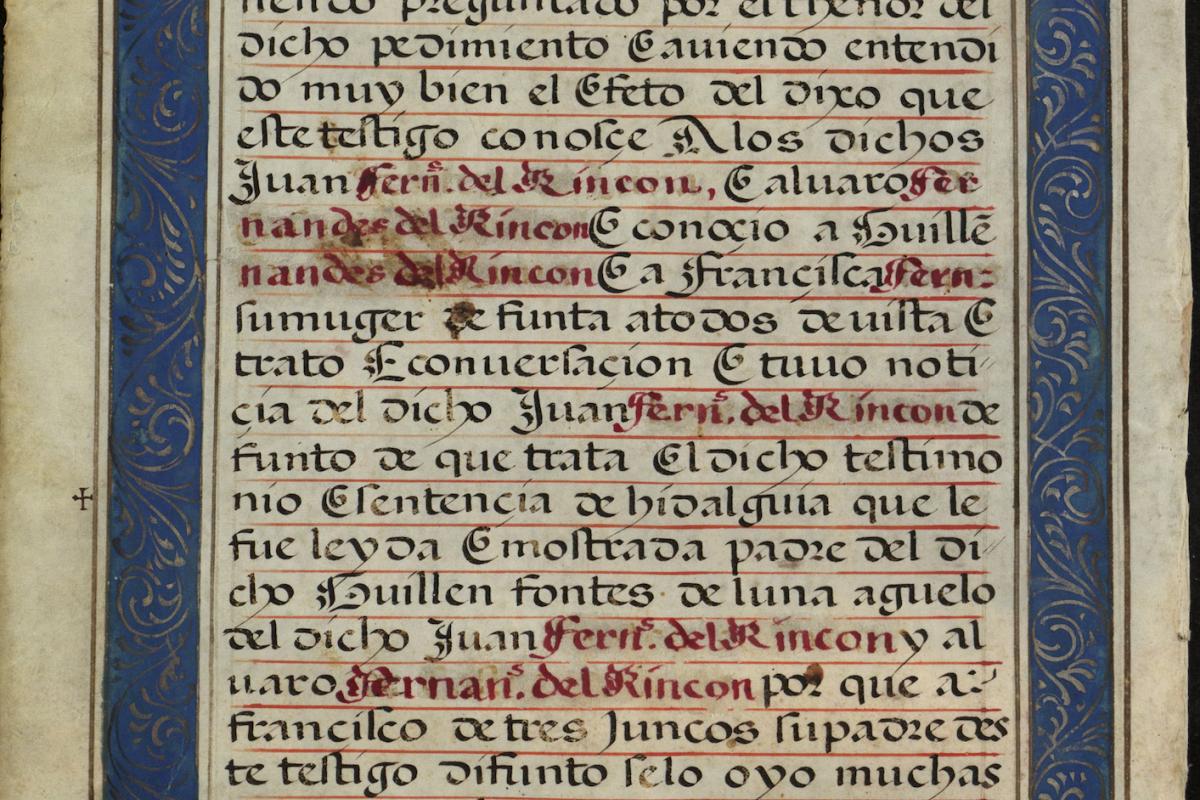

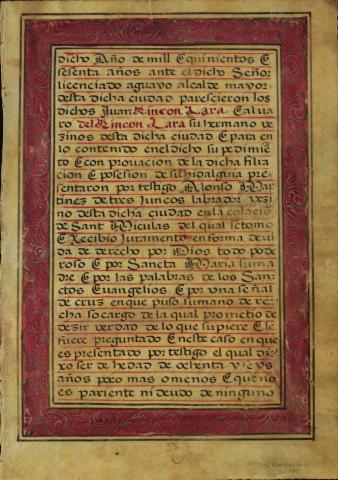

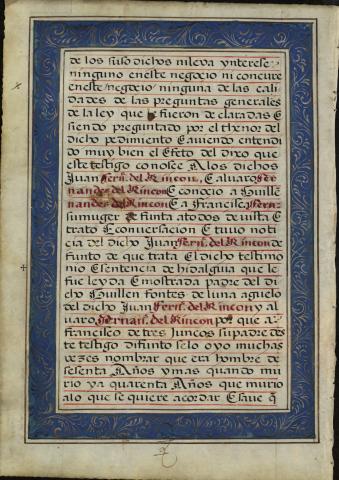

This parchment manuscript consists of one leaf, with twenty-seven lines of Spanish text on each side. The document is written in one column with a rounded hand and is enclosed by a two-centimeter decorative border that features scrolling silver branches on a background of red (recto) or blue (verso). While black ink dominates the text, every line is clearly ruled in red ink, as well as the surnames " (del) Rincon Lara" and "Fernandes del Rincon"; in one instance the first name "Juan" also appears in red. Several letters throughout the manuscript are both decorative and capitalized, but none more so than the letter "E," which is the Spanish language's early form of the word " and." What appears to be two types of small crosses appear in the left-hand margin of f.1 recto. The document is written in one hand and exhibits several corrections, all on f.1r. where the names in red have been re-written. For example, on f.1r., line 10, beneath the letter "n" in "Rincon" appear the discernible remnants of the letter "a". Portland State University's Library online catalog also states another error may exist:

The partial surname "nandes del Rincon", appearing in red at the beginning of a line, following the given name "Guille[n]" at the end of the preceding line, appears to be a scribal error repeating the partial surname "nandes del Rincon" (immediately following "Alvaro Fer"") which appears in red immediately above it at the beginning of the preceding line.

Despite these apparent errors, the document is excellently preserved. As a whole, the ink's pigment is vivid, and while the parchment on folio 1r, shows some "yellowing" effects of oxidation, folio 1 verso remains remarkably white. As a final note, a notary's rubric appears centered at the bottom of each side of the manuscript, certifying the leaf as a legal document.[2]

I believe the title supplied by the cataloguer should be amended because, at its worst, it is misleading and, at its best, it may only prove to be partially accurate. Given my comparisons between this manuscript and others[3], I believe that the document held in the Rose-Wright Collection dramatically differs from 16th- and 17th-century Spanish grants of arms. Foremost, as already stated, this manuscript is but one leaf from what was a larger work, and nowhere on this single leaf exists a coat of arms. It would be then, entirely speculative to assume that this leaf, or the subsequent contents of the other unknown leaves, provides enough evidence to warrant being cataloged as a "grant of arms."

The most explicit difference between this document and a Spanish grant of arms surfaces after translating the manuscript.[4] It is my belief that this manuscript is a specific type of Spanish legal document known as a Carta Ejecutoria, a position which is not only supported by my translation and comparison to other cartas of the period,[5] but which is also supported by the opinion of the Hispanic Society's Rare Book and Manuscript Curator, John O'Neill.[6] According to the website Medieval Writing, a Carta Ejecutoria is a "form of letters patent produced by the royal chancellery in late medieval Spain." As Amanda Dotseth writes, "these often elaborate[ly] decorated documents recorded court proceedings, including the testimony of witnesses, that proved the subject's status as a hidalgo, a member of the lower nobility." She continues, "Personal copies of patents were created for the hidalgo to use as physical proof of status." With these elements in mind, let us look at the manuscript as a text.

A short summary of the document shows that in 1560 the brothers Juan and Alvaro Fernandes del Rincon appear in court before an alcalde mayor (lawyer) in an unnamed city in the parish of Saint Nicholas. [7] The brothers bring with them a witness of approximately 86 years old, Alonso Martinez de Tresjuncos, who swears "by God Almighty and by Holy Mary, mother of God, and by the words of the Holy Evangels and by a sign of the cross" that Juan and Alvaro descend from nobility because he both knew their father and recalls hearing his own father speak often of their great grandfather's nobility[8]. Unfortunately, the text trails off and onto the other missing folios before more information can be gathered.

At this point, it is important to note that aside from claiming hidalguia, one's nobility could be legally challenged by a town council. In the court proceedings that would follow, Mauricio Drelichman writes that:

To win a lawsuit, a claimant of hidalguia would have to prove, at a minimum, that his father and grandfather had been hidalgos, widely reputed as such in the places where they had lived. He had therefore to produce witnesses that had known (or claimed to have known) his father and grandfather and could confirm their status ("Sons of Something",8).

The description in this single folio meets these "minimum requirements," reinforcing my belief that this manuscript is a single leaf from a carta ejecutoria.

In her article titled, "Implementation of Pure-Blood Statutes in Sixteenth Century Toledo," Linda Martz says that in the 1550s, Spain's crown had a difficult time selling hidalguia due to its high price, and that there was another way to attain nobility through "an appeal to the [two] chancery or appeal courts [...] which would issue to successful litigants cartas ejecutorias, leading to the creation of hijosdalgo de ejecutoria (nobles created by court judgment)" (249). It should be noted, that in 1560 there were only two Royal Chancery Courts in the Crown of Castille, one in Valladolid and the other in Granada,[9] which may prove to be very useful in situating the manuscript within a specific region of Spain. The probability that this manuscript derives from one of these two locales is reinforced by the existence of a Saint Nicolas (San Niculas) Parish in each of the cities.[10]

Regardless of possible locales, ultimately one can only speculate whether the Fernandes brothers had had their hidalguia challenged by a municipality, or whether they attained nobility through a court judgment. One can also speculate that the two brothers were granted or retained hidalguia due to the existence of a beautifully decorated carta ejecutoria, but, though the correlation may be strong, it is more important to remain in the realm of fact and to look at the cultural ramifications of having nobility in mid-sixteenth-century Spain.

According to a website for an exhibition at the University of Pennsylvania, "there was no greater or more absolute social distinction in early modern Spain than between noble and non-noble." Though one might wonder how these distinctions had become "absolute," those questions are readily answered by knowing the tangible benefits of nobility. The library's website reads:

Nobles could not be taxed, nor imprisoned for indebtedness; they could not be tortured except in cases of treason; their possessions could not be taken from them in civil suits, and if they faced the threat of execution they could choose decapitation rather than hanging. These corporeal benefits are valuable in understanding the societal privilege they denote, but, they are even more important for grasping the general lack of privilege that existed amongst the masses in early modern Spain.

In his research on hidalguia and litigation in sixteenth-century Spain, Mauricio Drelichman trolled the massive holdings of the Archivo de la Real Chancilleria de Valladolid, which "had jurisdiction over the northern half of Castile" (5). Drelichman compiled, "a time series of the surviving 42,313 cases filed with the Valladolid Chancery Court [...] which extends between 1490 and 1834, [and] shows a large increase in legal activity in the mid-sixteenth century, thus confirming the impression that the pace of ennoblement was fastest during that period" (3). Given the immense privileges associated with nobility, it is of little shock that so many common people would attempt to gain or assert their hidalguia. One can only wonder whether in 1560 Juan and Alvaro Fernandes del Rincon were trying to establish their nobility, or whether the two brothers had their nobility challenged in court, but what is clear is that Portland State University's Rose-Wright Collection holds a carta ejecutoria that provides a unique glimpse at the nexus where Spain's sixteenth-century cultural and legal histories collide.

Notes:

[1] An interview with the rare book dealer Phil Pirages, revealed that this leaf is at least one of six, which he acquired from another dealer at an unrecollected date. No information was provided as to who had acquired the other leaves.

[2] John O'Neill, Curator, Rare Books Room, The Hispanic Society, Interview, July 15th, 2008

[3] For some contemporary grants of arms see:

http://home.pacbell.net/nelsnfam/mexico.htm

http://heraldry.freeservers.com/certificates.html

http://www.prbm.com/quotes/i.htm?featured_book_Basabe_Urasandi_Illuminat...

[4] My countless thanks to my friend Jim Ruppa for his assistance in this translation; without his help, much of this work would have been impossible.

[5] On 12 July 2008, a search for "Carta Ejecutoria" in the online database Digital Scriptorium yielded nine matches. See "Works Cited" for a complete list.

[6] "... it appears to be a typical 'carta ejecutoria' [...], probably of higher quality given the penmanship, page decoration, and the fact that it appears to be written on parchment. These cartas [...] [are] of varying quality depending on how much one was willing to pay a scribe to do it. It is impossible to tell how long your manuscript originally was. Better quality cartas usually had a portrait of the family at the start and a portrait of the king towards the end. They were all signed and dated, specifying the place where the manuscript was executed."

[7] "Since the corregidores were often inadequately versed in law, each usually received advice from two trained lawyers, termed alcaldes mayores, who specialized in criminal and civil law, respectively." The Columbia Encyclopedia. See "Works Cited" for full citation.

[8] For a full Spanish transcription and English translation, see Appendix One and Two, respectively.

[9] Ana Maria Carabias Torres, "The Struggle Between University Students in the Spanish Modern Age."

[10] The Saint Nicholas Center, www.stnicholascenter.org

Appendix

"Leaf from a grant of arms to Juan and Alvaro Fernandes del Rincon." 1630?

Portland State University. Brandford P. Millar Library. Manuscript. Rose-

Wright 18. Accessed 19 June 2008.

Folio 1 Recto

dicho Ano de mill E quinientos E sesenta anos ante el dicho Senor licenciado aguayo (alguacil?) alcalde mayor desta dicha ciudad parescieron los dichos Juan Rincon Lara E alvaro del Rincon Lara su hermano vezinos desta dicha ciudad E para en lo contenido en el dicho su pedimie[n]to E con provacion de la dicha filiacion E posesion de su hidalguia presentaron por testigo Alonso Martinez de tres Juncos labrador vezino desta dicha ciudad en la colacio[n] de Sant Miculas del qual se tomo E Recibio Juramento en forma de vida de derecho por Dios todo pode roso E por Sancta Maria su madre E por las palabras de los San:ctos E uangelicos E por una senal de cruz en que puso su mano derecha so cargo de la qual prometio de dezir verdad de lo que supiere E le fuere preguntado E neste caso en que es presentado por testigo el qual dixo ser de hedad de ochenta y seys anos poco mas o menos E que no es partiente ni deudo de ninguno

Folio 1 Verso

de los suso dichos nileva ynterese ninguno en este negocio ni concure en este/negocio ninguna de las calidades de las preguntas generales de la ley que le fueron de clara das E siendo preguntado por el thenor del dicho pedimiento E aviendo entendido muy bien el Efe[c]to del dixo que este testigo conosce A los dichos Juan Fern.s del Rincon, E alvaro Fernandes del Rincon E conocio a Guille[n] nandes del Rincon E a Francisca Fern: su muger defunta a todos de vista E trato E conversacion E tuvo noticia del dicho Juan Fern.s del Rincon defunto de que trata El dicho testimonio E sentencia de hidalguia que le fue leyda E mostrada padre del dicho Guillen fontes de luna aguelo del dicho Juan Fern.s del Rincon y alvaro Fernan.s del Rincon por que a francisco de tres Juncos su padre deste testigo difunto se lo oyo muchas vezes nombrar que era hombre de sesenta Anos y mas quando murio ya quarenta Anos que murio a lo que se quiere acordar E save q[ue?]

Translated by Jim Ruppa, 10 July 2008.

In the year 1560, in front of the aforementioned lawyer aguayo Alcalde Mayor (Lawyer) of this city, appeared Juan Rincon Lara and Alvaro del Rincon Lara, his brother, residents of this city (...)contents of the aforementioned petition with proof of the connection to the possession of nobility (hidalguia). They presented as a witness Alonso Martinez de Tres Juncos, laborer and resident of this city in the Parish of Sant Niculas which he takes part. He took an oath swearing by God Almighty and by Holy Mary, mother of God, and by the words of the Holy Evangels and by a sign of the cross that he made by which he promised to tell the truth as he knew it. He was asked about this case in which he is presented as a witness in which he said he was 86 years old (more or less) and that he is neither relative nor indebted to any of the above-mentioned persons, nor does he have any interest in this affair nor does he share in this affair any of the general questions of the law that were declared to him. Also, being asked about the meaning of said petition and having understood very well the effect, this witness said that he knows Juan F. del Rincon and Alvaro F del Rincon and that he met Guille F de Rincon and Francisca Fernandes, his deceased wife. (he knew them all by sight, and to speak to) and that he received news from the said Juan F de Rincon (deceased???) about the testimony and the declaration of nobility that was read and showed to the father of Guillen Fontes de Luna, grandfather of Juan and Alvaro F. de Rincon, because Francisco de Tres Juncos, the deceased father of this witness had heard named many times that he was a man of 60 and when he died 40 yrs ago (?), and, as he can recall, he knows that...