Nuremberg Chronicle | Liber Chronicarum

1493

Printed in Nuremberg, Germany

Language: Latin

Trimmed down, perhaps missing leaves. 18th-century binding

John Kidney, Medieval Portland Capstone Student, Summer 2014:

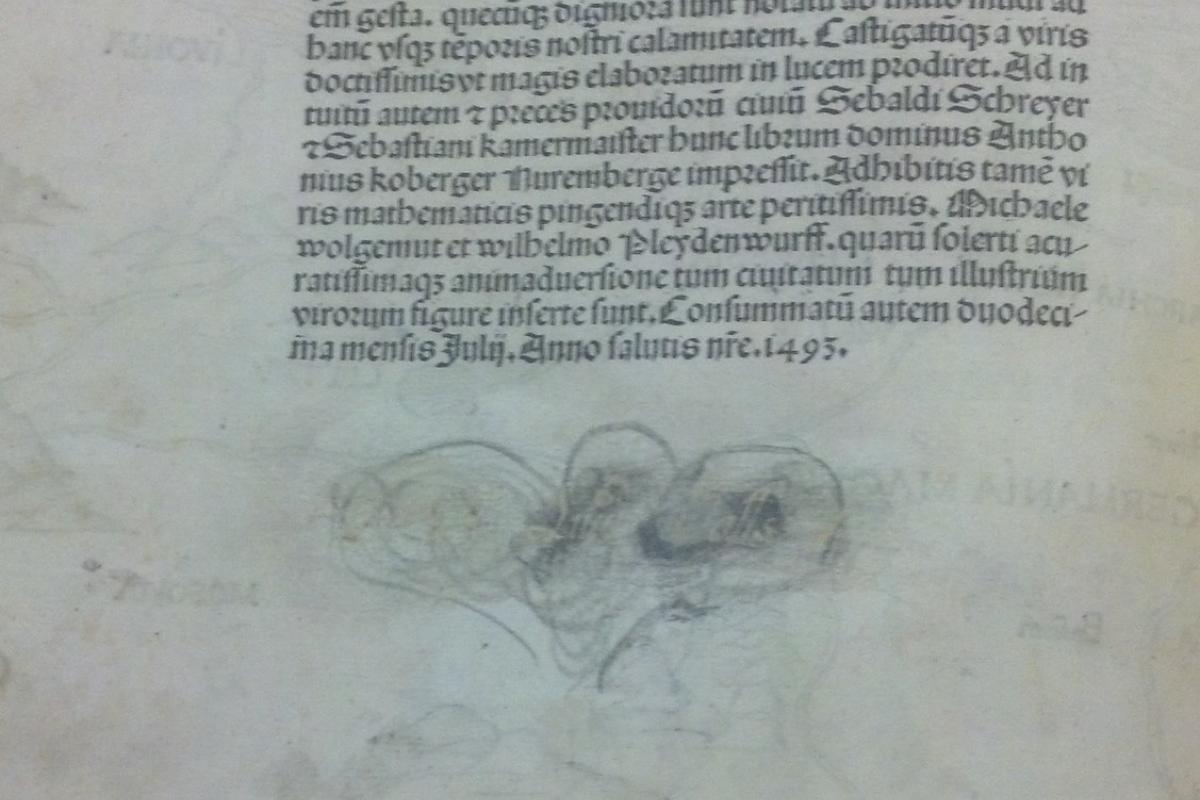

Liber Chronicarum is an early printed biblical history which begins with Creation and ends with an appendix on the European cities which are mentioned throughout the test. It was compiled in Latin by Hartmann Schedel, a medical doctor in the city of Nuremburg in 1493, and is widely known in English as the Nuremburg Chronicle for this reason. The Chronicle was printed by Anton Koberger with the original printing being Latin, and a second run printed in German towards the end of the same year. The total printed volumes in both Latin and German were around 2500, of which, approximately 400 Latin texts and 300 German survived into the twentieth century.

This particular copy has pencil notes on some pages that direct the reader where to look for use of the same woodcut on other folios. This volume was rebound and cut, most likely due to water damage, and there are examples of pages folded over to accommodate the cutting of the original leaves and the surviving printed images. In contrast to the other copy of this text in John Wilson collection with a binding contemporary with its late fifteenth-century printing, this volume was cut down and re-bound in what was most likely the mid to late 19th century. This binding was in brown leather with a gilded rope pattern along the inside edge of the boards. In the upper left corner of the cover board a small tag bears a booksellers mark of "Doxey, San Francisco". Doxey was an importer and publisher who published the literary magazine declared bankruptcy and closed his shop in 1899, and it is believed that this volume of the Nuremburg Chronicle is the one listed in Volume 26 of the American Stationer from October of 1889. The Stationer states that Doxey was releasing in mid-November of that year a first edition of the Nuremberg Chronicle, which was "Rebound by Zaehnsdorf of London, in full Levant, and it is in a sound and perfect condition" (American Stationer 1889). It is likely that this is the same volume yet no further evidence has been found.

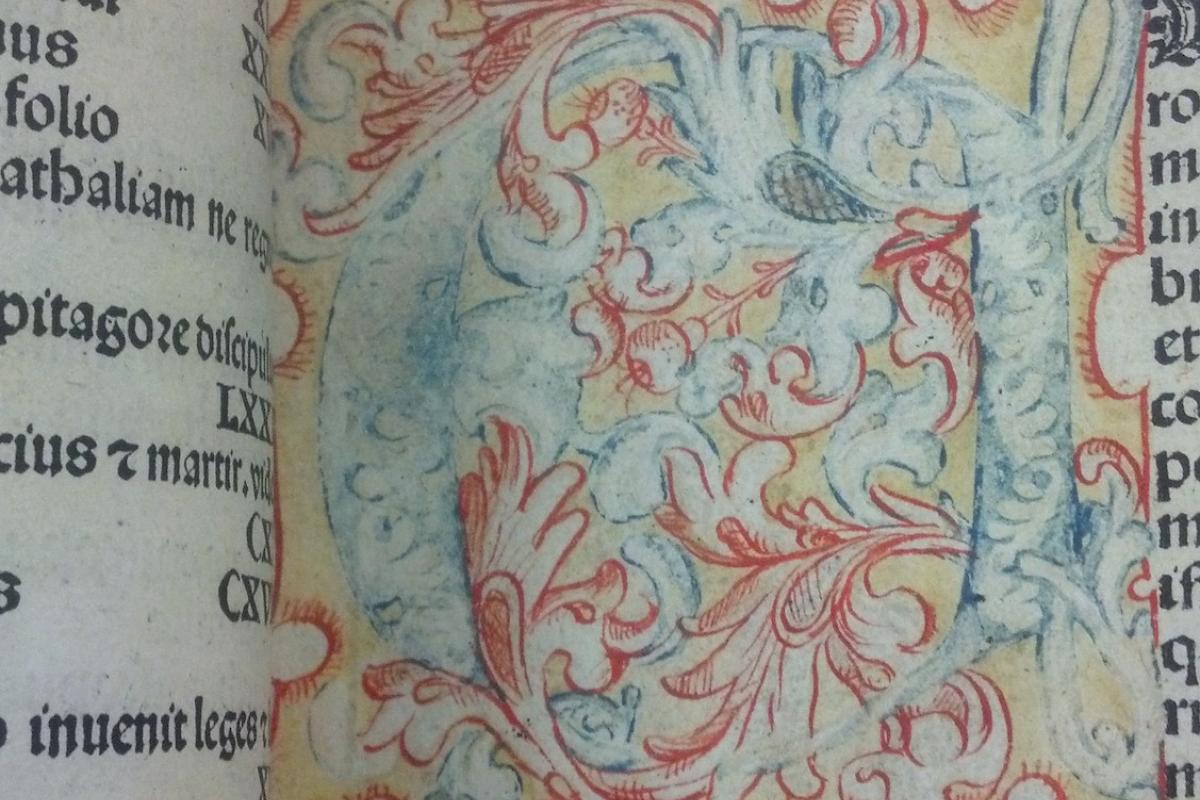

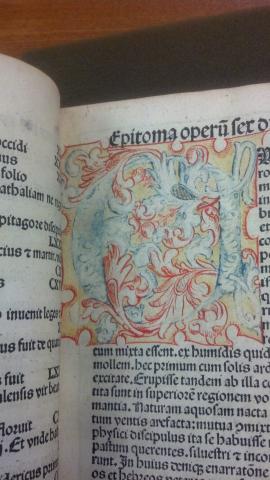

During the rebinding process many of the leaves were supported with paper backing into the binding in every instance where there is a full spread illustration. The first leaf of the volume with the woodcut lettering (the title page of the index) was most likely cut from the original volume and then inserted onto a new leaf of paper. Only the first folio of the index has any color added. The volume was printed with space for rubrication at each new letter of the alphabet through the index. In this volume the "A" is the only one completed, which is faded to an orange and green coloring. It should be mentioned that this is the only coloring done anywhere in this volume. Many copies were lavishly and expertly colored after printing by the purchaser of the book, and it is unclear when this initial attempt at coloring was done and why it is the only place it exists.

The index also contains an interesting effort by someone to scratch out the Latin word "Papa" when it appears in the index. This scratching continues for a few leaves and then ends. There are very few handwritten notes throughout this volume, while the collection's other copy has many. There are a few penciled notes however, annotating when some of the woodcuts were used in multiple places. It is widely known that many of the woodcuts were used in multiple places throughout the book, and only the name of the person or place depicted was changed (Wilson, The Making). The recto of Folio 51 is a good example of these annotations with a note stating to "see Folio 42." This occurs again on Folio 59 directing to Folio 37 and "also 69." This person's effort ceases at Folio 60, when no other indications of where the woodcuts were reused continues thereafter.

Evidence of the difficulties of the repair and rebinding occurs on Folio 64 where the full spread map from the verso of Folio 63 extends beyond where the rest of the volume was re-cut; this was solved by folding over approximately an inch of the page, which is still in good condition. Various other condition issues occurring include: ink drops on Folio 102, a small tear in page on Folio 105, stains in upper left corner verso. Folio 121, green ink drops on recto Folio 134 and verso Folio 133, and small tear at Folio 161 at bottom of the page. There are no pages missing in the volume as compared to the other copy owned by the John Wilson collection

In both of the Library volumes, when comparing them side by side, Folio 162 jumped while printing and led to a blurred double print towards the top of the leaves, it is very clear around the word "Folio." It does raise the question whether many of the other volumes had the same problem. Another interesting mistake was that both volumes have two leaves marked "Folio 231," this is because Folio 229 was mistakenly listed as CCXXXI in Roman numerals as opposed to CCXXIX.

A major difference between the two volumes in the Library occurs because of binding: both of the copies in the John Wilson Collection have the supplemental pages which were not part of the original printing, but included later, however the volume with the contemporary binding has leaves in the order in which they were to appear starting at Folio 259. This volume has the supplemental pages bound at the end of the regular volume. Without seeing them side by side one might think pages were missing.

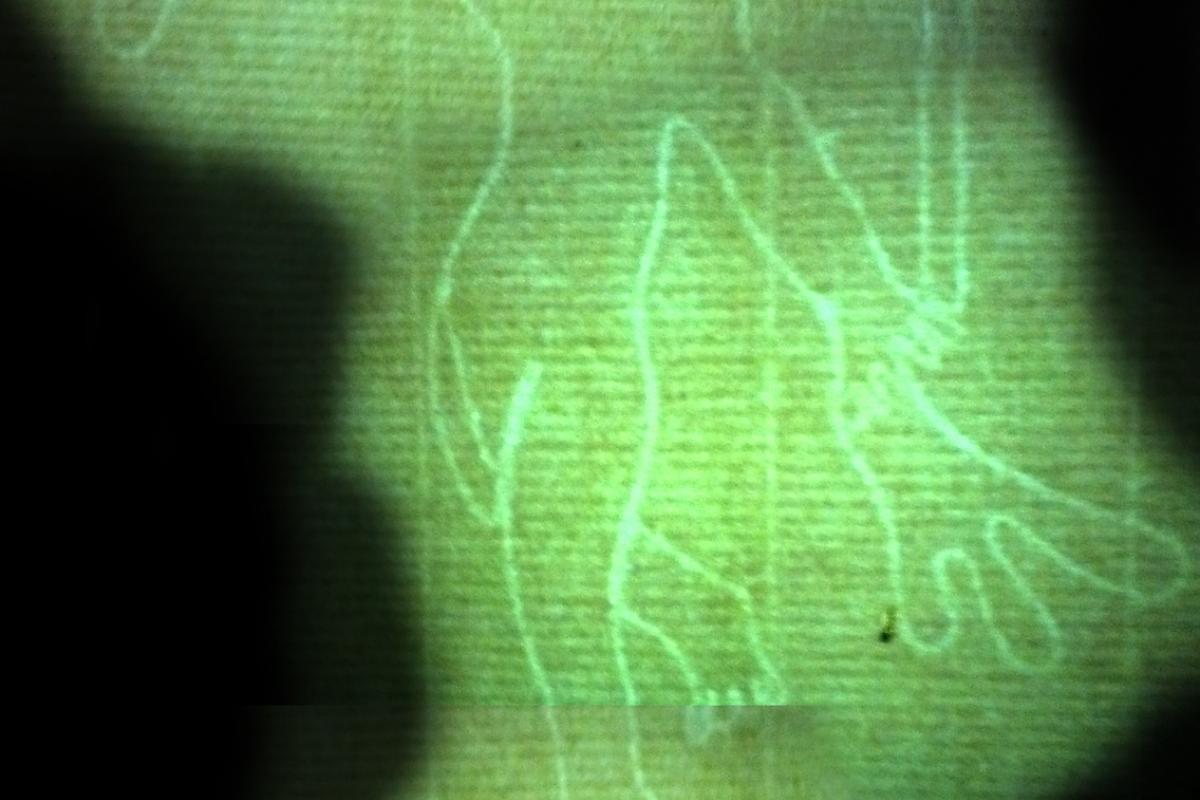

The last leaf of the volume has graphite pencil rubbing where someone was clearly trying to bring out the watermark of the paper or cover something up. A photo was digitally enhanced to reveal hand lettering underneath, which is possibly a name, the only clear part is the surname which appears to be "Walls."

The paper's condition is aged throughout with some staining and water damage. The nineteenth century binding is beginning to crack towards the last leaves, but remains intact with no loose leaves. There is an unusually large watermark depicting a man standing on a sphere with cloth stretched from hand to hand. Research into this watermark yielded no results, but a digitally enhanced photograph is included for further research.

The John Wilson Collection provides a rare opportunity to view two of the first edition Latin Nuremberg Chronicles in the same room. These volumes are part of the early history of printing with moveable type and woodblock illustrations, and were the early work of Albrecht Durer, and the printing of Anton Koberger. Much of the book's significance is due to the lavish illustrations and the designs combined with text throughout the volume. The care that was given to this aspect of the design and layout was revolutionary for printed material at the dawn of the 16th century.

Bibliography

American Stationer. "William Doxey will Issue..." The American Stationer, October 31, 1889: 2.

Chipps, Laurie. "Sarah E. Raymond Fitzwilliam and the "Nuremberg Chronicle.” Art through the Pages: Library Collections at the Art Institute of Chicago (Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies) 34, no. 2 (2008): 35-36, 93.

Hall, Cynthia A. "Before the Apocalypse: German Prints and Illustrated Books, 1450-1500." Harvard University Art Museums Bulletin (The President and Fellows of Harvard College) 4, no. 2 (Spring 1996): 8-29.

Schedel, Hartmann. Liber Chronicarum: Translation. 1st ed. Boston, Mass.: Selim S. Nahas Press, 2010.

Smith, Jeffrey Chipps. "Gothic and Renaissance Art in Nuremberg 1300-1550. Nuremberg." The Burlington Magazine (Burlington Magazine Publications Ltd.) 128, no. 1001 (August 1986): 627-629.

Wilson, Adrian. "The Early Drawings for the Nuremberg Chronicle." Master Drawings, vol. 13, No. 2 (Summer, 1975), pp. 115-130+181-185 (Master Drawings Association) 13, no. 2 (Summer 1975): 115-130+181-185.

---. The Making of the Nuremberg Chronicle. Amsterdam: Nico Israel, 1977.