Palm Sunday Processional Leaf

Palm Sunday Processional Leaf

Italian (Florence), 15th century

Language: Latin

height 20 cm

width 14 cm

Portland State University Library Special Collections

Mss. 27, Rose-Wright Manuscript Collection no. 19

Palm Sunday Processional Audio featuring vocalists Josephine Peterson, Angelica Hesse, and Shigemi Getter

Medieval Portland Capstone Student Project, 2018

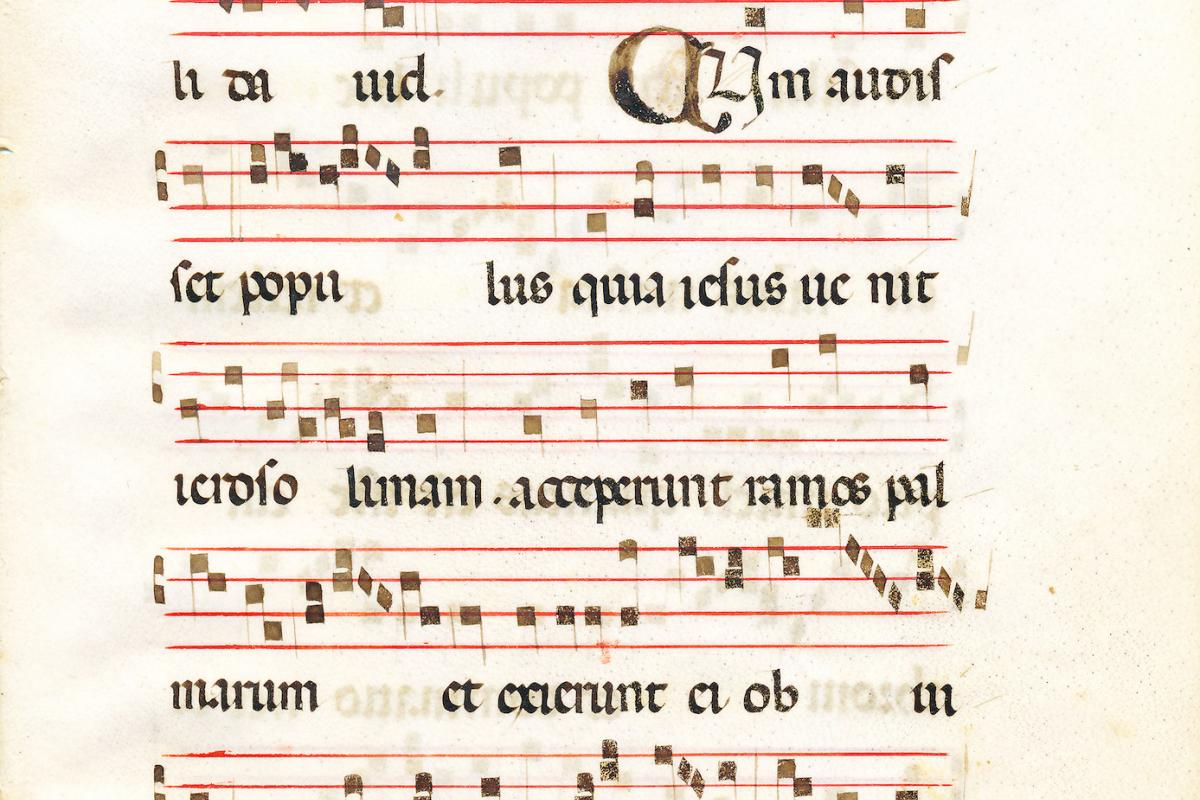

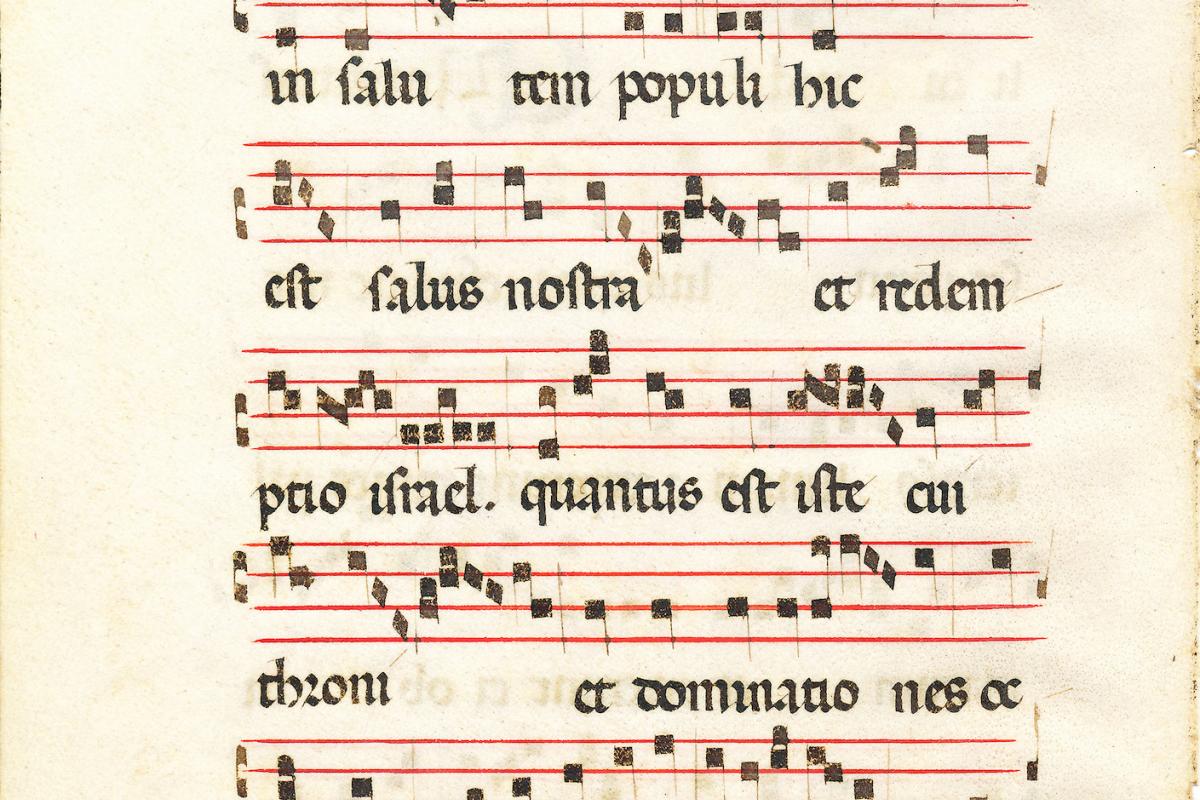

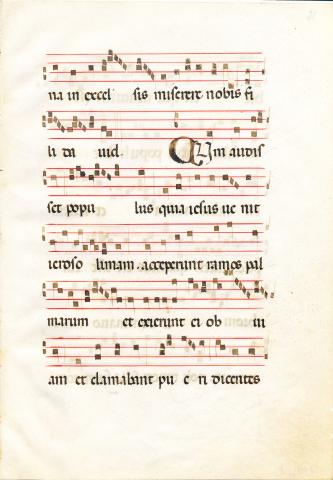

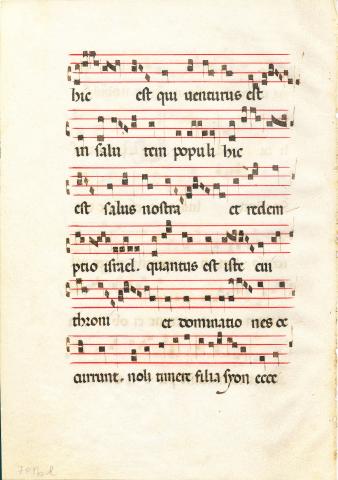

na in excelsis miserere nobis fili david. Cum audisset populus quia iesus venit Hierosolimam, acceperunt ramos palmarum et exierunt ei ob viam et clamabant pueri dicentes hic est qui venturus est in salutem populi, hic est salus nostra et redemptio israel. Quantus est iste cui throni et dominationes occurrunt. Noli timere filia Syon ecce

Translation:

(Hosanna?) in the highest, have mercy on us, son of David. When the people heard that Jesus had come to Jerusalem, they took palm branches and ran out into the road and the children (of Israel) cried out saying here is the one who would come for the salvation of the people, he is our salvation and the redemption of Israel. How great is the one to whom thrones and dominions run! Do not be afraid daughter of Zion, behold

Allison Moody, Medieval Portland Senior Capstone Student, 2008

This manuscript leaf of a Palm Sunday Processional, part of the Rose-Wright Manuscript Collection housed at Portland State University Library, is a typical example of Italian Catholic liturgical music of the 15th century. It is a single 20 x 14cm leaf removed from a larger manuscript; evidence of binding exists along one edge. Both sides of the page contain musical notation and text. The margins are wide and unequal: the outer edge and bottom margin are both significantly wider than the other two. Each side contains six four-lined staves of red ink, with notation.

Unlike modern music with standardized clefs including treble, bass, tenor, and alto clefs, medieval music used what is commonly referred to as a "movable clef" or "movable C." This simply means that middle C could be on any line of the staff, and was indicated by a calligraphic "C" around the chosen line. This manuscript is written in "C" clef with "C" alternating between the second and third lines.

The notation contains square and diamond-shaped notes with stems, and includes measure markers and check mark style note leads at the end of every line. A note correction exists over the word "Nobis." The notation style of this processional is an example of the influences of French notation combined with Italian style, predominantly a continuation and development of the Ars Nova. This notation style, while existing in its basic form after it was developed, was limited and was considered obsolete in 1412. Italian composers and scribes sought to create a notation form that would allow for the articulation of novel and complex rhythms. Notation continued to change, though early 15th-century styles saw a shift back to a more simple style, resulting in a more advanced style that appears less complex. In this example, the basic rhythmic combinations and harmonic notation of the Ars Nova is noticeable, though pared down to be easier to read. However, Parrish suggests that "Italian scribes favored the use of a six-lined staff," while this example exhibits a four-lined staff.

The calligraphy style of the text shows the direct influence of the Humanist movement in Italy, which dominated heavily in Rome and Florence in the 15th century. Humanist civic interests revolved around bettering society through the revival of Classical culture and writings. These interests in ancient manuscripts lead to a great deal of re-copying of manuscripts in Florence during the 15th century. While this wasn't a focus on music manuscripts, but on classical literature, it was still producing a culture of high manuscript production and appreciation. Calligraphy was impacted by Humanistic interest in the reforming of scripts and bookmaking with the goal of promoting literacy. The calligraphy in this manuscript is a typical example of the Humanist efforts to create a standard, legible script. It is a round-hand, lowercase minuscule style, with roman capitals, that is now generally known as "humanistica."

Philosophy and theology of religious teaching in 15th-century Florence were dominated by the idea that images were the most profitable way to instruct an "illiterate" population (those who are unable to read or understand Latin). Music was a part of liturgy aimed at worship, while sermons and images were intended to be didactic. Moreover, choirs were not comprised of volunteer churchgoers as they are today but consisted of monks, who would have been literate and educated in Latin and the reading of musical notation. Because the popular religious ideas about didactic methods at the time were not focused on music, and Florence was not in an era of great prosperity, the production of music manuscripts was not large. The small scale and lack of decorative elements on this Palm Sunday Processional manuscript could be attributed to the social and religious atmosphere.

Appendix

The text from this page can be transcribed as follows:

" ... na in excelsis miserere nobis fili david. Cum audisset populus quia iesus venit ierosolimam, acceperunt ramos palmarum et exierunt ei ob viam et clamabant pueri dicentes hic est qui venturus est in salutem populi, hic est salus nostra et redemptio israel. Quantus est iste cui throni et dominationes occurrunt. Noli timere filia syon ecce ... "

It is the text that establishes this manuscript as a processional for Palm Sunday. It references Jesus entering Jerusalem (iesus venit ierosolimam - "Jesus has come to Jerusalem") and the use of palm branches ("ramos palmarum"). Palm Sunday is the last Sunday in Lent and commences Holy Week. In Latin it is known as Dominica in Palmis, Dominica or Dies Palmarum. Because Palm Sunday commemorates Christ's triumphal entry into Jerusalem and the joyful response of the people, the Palm Sunday procession in the Mass often involved carrying in a representation of Christ on a donkey. It is also the only mass where palm branches are referenced and used: during the processional, while the choir sings, the palm branches are blessed and distributed.

The order of a Palm Sunday mass begins with a benediction of the palms, the processional, and then the mass. As the commencement of Holy Week, Palm Sunday is a commemorative day in the life of Christ, and thus requires a special mass. There are different types of masses, which indicate the level of ritual. A Palm Sunday mass would likely fall under the Solemn High Mass structure. This allows for the use of a processional, and requires a bishop to be present. Everything in a High Mass is intoned, and was sung or chanted without the accompaniment of musical instruments until later in the Renaissance. The Palm Sunday mass not only includes a benediction of palms and a processional, but also a reading of the Gospel of the Passion according to St. Matthew. It also eliminates the Gloria Patri from the mass structure, and, as part of Holy Week, includes the Miserere in the first psalm at lauds and also at the end. The miserere followed by the cum audisset, as in this text, is a common Palm Sunday processional structure.

Bibliography:

Boorman, Stanley, ed. Studies in the performance of late mediaeval music. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1983.

Carter, Tim. Music, Patronage and Printing in Late Renaissance Florence. Burlington, VT: 2000.

Covi, Dario A. Lettering in Fifteenth-Century Florentine Painting. College Art Association: The Art Bulletin, Vol. 45, No. 1 (Mar. 1963), pp. 1-17.

Dickinson, Edward. Music in the history of the western church, with an introduction on religious music among primitive and ancient peoples. New York: Haskell House Publishers, 1969.

Fallows, David; Knighton, Tess, ed. Companion to Medieval and Renaissance Music. New York, NY: Schirmer Books, 1992.

Harvard, Stephen. An italic copybook: the Cataneo. New York, N.Y.: Dept. of Printing and Graphic Arts of the Houghton Library, Harvard University and the Newberry Library by Taplinger Pub. Co., 1981.

Hughes, Andrew. Medieval music: the sixth liberal art. Toronto; Buffalo: University of Toronto Press, 1980.

Palladino, Pia. Treasures of a lost art: Italian manuscript painting of the Middle Ages and Renaissance. New Haven, Conn.: Metropolitan Museum of Art, Yale University Press, 2003.

Parrish, Carl. The notation of medieval music. New York, NY: Pendragon Press, 1978, c1959.

Suggestions for further reading:

- Covi, Dario A. Lettering in Fifteenth-Century Florentine Painting. The Art Bulletin, Vol. 45, No. 1 (Mar. 1963), pp. 1-17.

- Parrish, Carl. The notation of medieval music. New York, NY: Pendragon Press, 1978, c1959.