Rationale Divinorum Officiorum

Rationale Divinorum Officiorum

German (Strasbourg), 1479

Author: William (Guillaume) Durand

Printed by Georg Husner in Strasbourg, Germany

Re-bound in the late 19th century in Britain before being sold to American John Wilson.

Multnomah County Library, John Wilson Special Collections: W- 093 D9487r\

Shannon Knight, Medieval Portland Capstone 2010

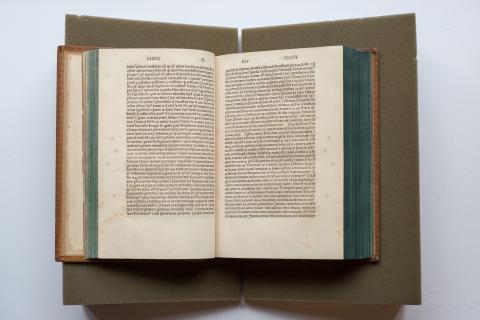

The Portland, OR library owns a clear copy of Durand's allegorical exposition, Rationale Divinorum Officiorum, likely printed towards the end of the fifteenth century by Georg Husner in Strasbourg, Germany, containing contemporary Latin marginalia, and re-bound in the late nineteenth century in Britain before being sold to American John Wilson.

Guillaume Durand [1], Bishop of Mende, France, was a premier liturgical scholar of the Middle Ages, and author of the highly influential and much disseminated [2] exegesis [3], Rationale Divinorum Officiorum, written in 1286 [4]. The Rationale has proven of utmost import for art historians [5] and medievalists [6] in understanding the symbolism of all aspects of the liturgy, as well as the medieval worldview and multiple modes through which it was interpreted [7]. Durand's Rationale, first printed by Fust and Schoeffer in Mainz, Germany in 1459 [8], spread quickly across Europe. One copy of the incunabulum, a book printed during this period, is located in Portland, OR at the Central Library.

The library's card catalog information for the Rationale, unfortunately, pertains to another copy of the same book [9]. A bookplate and note within the cover show that John Wilson purchased the book in September 1894 [10]. A clipping [11] pasted below it advertises that the book was sold by William Ridler, a merchant who worked from c. 1876 to c. 1914 on Booksellers' Row in London [12]. The copy falsely claims that the book was printed in 1459, the date of the first printing of the text, likely due to the date and city of the first printing being tooled into the spine of the cover; additionally, it incorrectly describes the book as being printed on vellum, rather than paper.

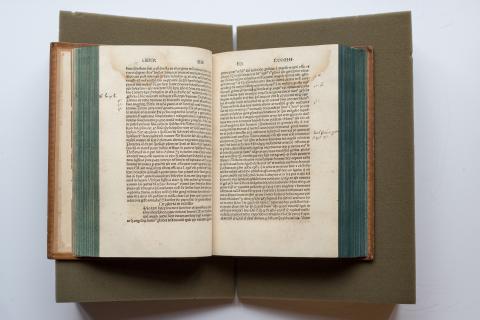

The book is bound in polished calfskin treated with acid for a look known as "tree calf," with tooled scrolls and a red leather inlay with gold lettering on the spine, all of which had not become common till the mid-18th century [13], revealing that the book had been rebound since its initial printing. Machine-made [14] endpapers added during this rebinding to protect the original paper offer more clues, most precisely in their watermarks [15], identifying images pressed or molded into the paper, which name their maker as A. Cowan & Sons, a Scottish papermaking company founded in 1779, which was among the first in Britain to switch to the paper-making machine [16]. Located on a rear endpaper, partially hidden in the binding, is a watermark of the year 1848, loosely [17] demarking the date of the incunabulum's rebinding.

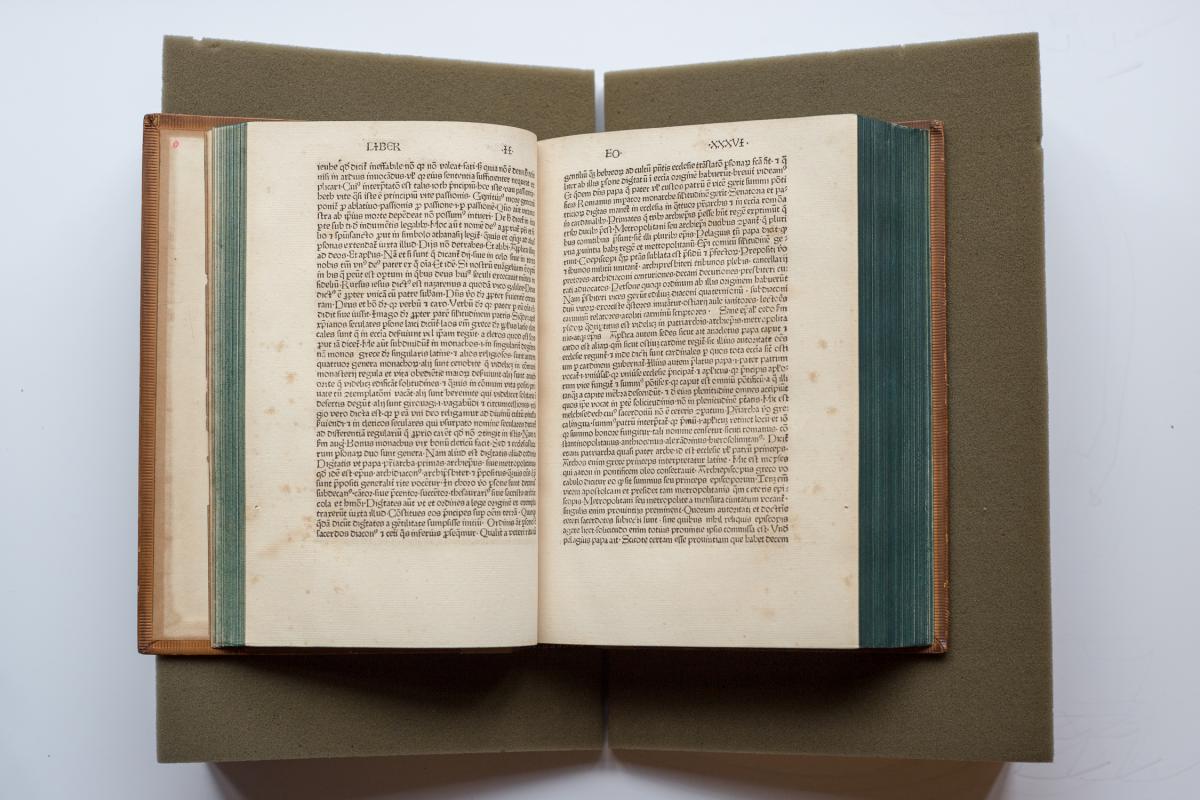

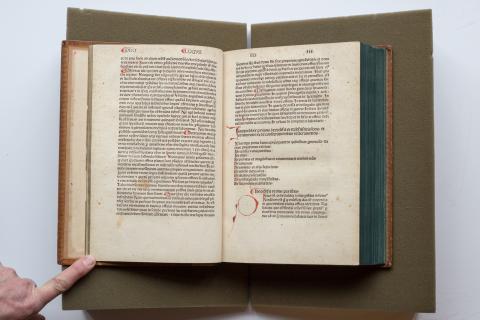

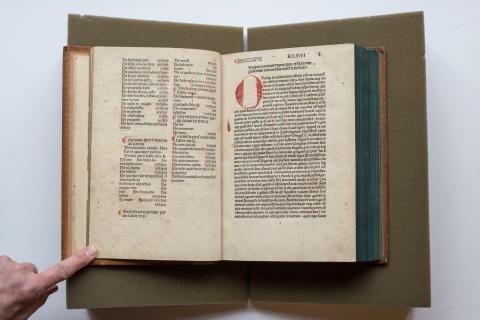

The paper of the original manuscript contains two differing watermarks: a bull's head with an open mouth and a circle beneath it [18], and a tall cross on a triple-mount [19]. Similar forms [20] of both watermarks appear prevalent in papers produced in the second half of the 1400s [21]. The folio's typeface is a gothic rotunda, which was widely used in the fifteenth century [22]. Cross-examining other incunabula [23] printed during this time revealed other Rationale produced with the same number of leaves, and full sheets of folded paper, meaning they were printed with the same or very similar text layouts. These were all the work of Georg Husner, a printer of Strasbourg, Germany, and a former goldsmith [24]. Husner ran a medium-scale shop and produced 129 books between 1479 and 1505 [25], 72% of which were on Catholic subjects [26]. Between c.1478 and 1493, Goff records Husner to have produced eight editions of the Rationale [27]; Husner is very likely the printer of Portland's copy.

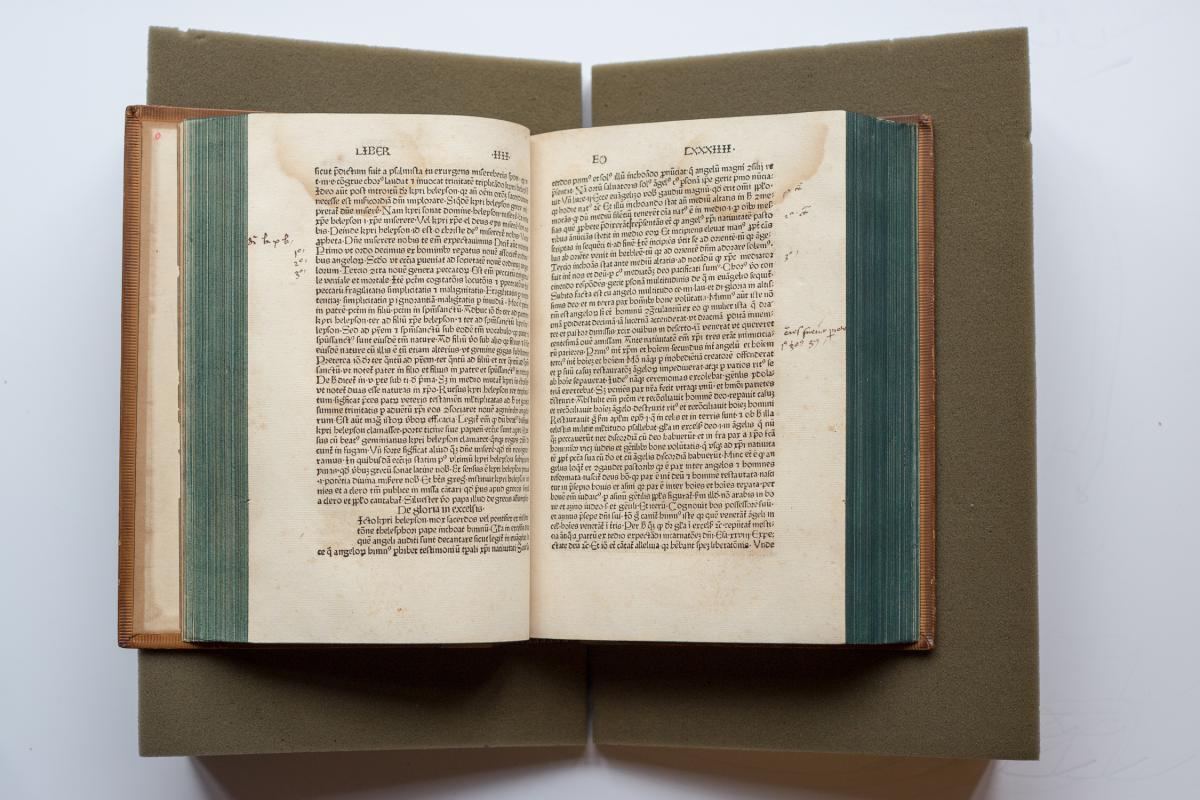

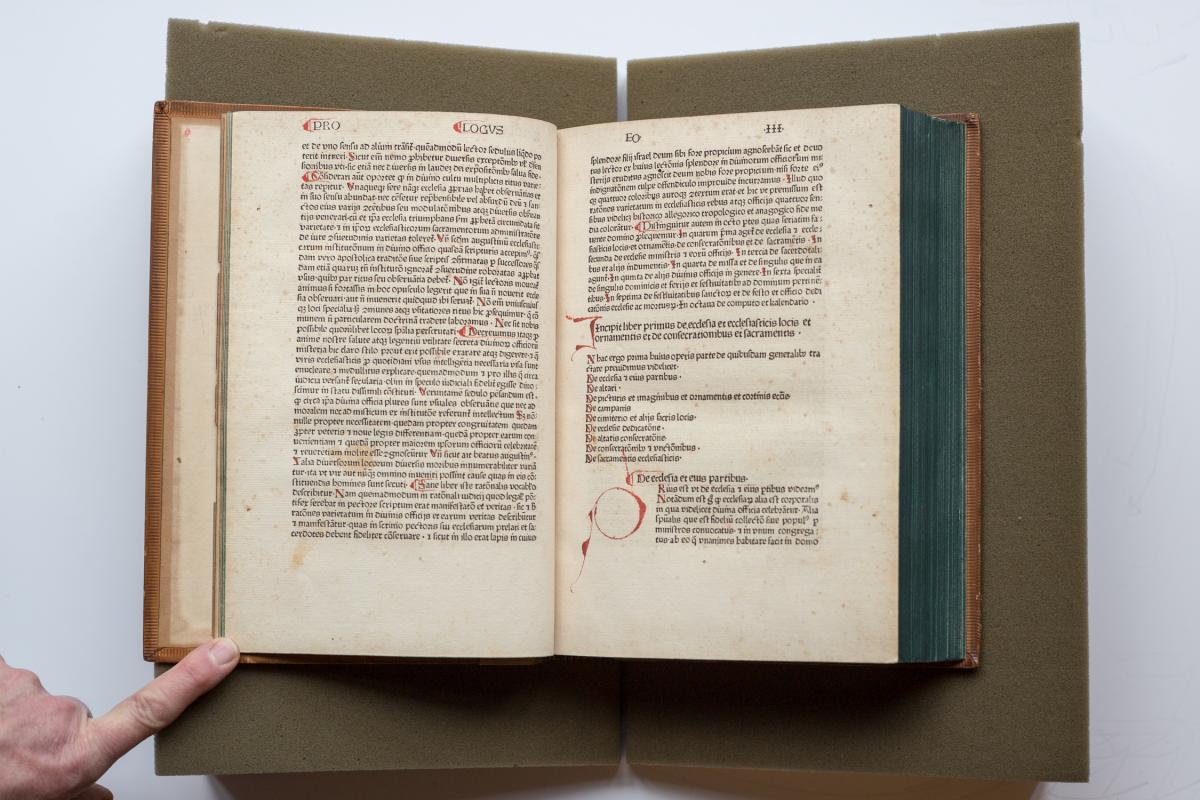

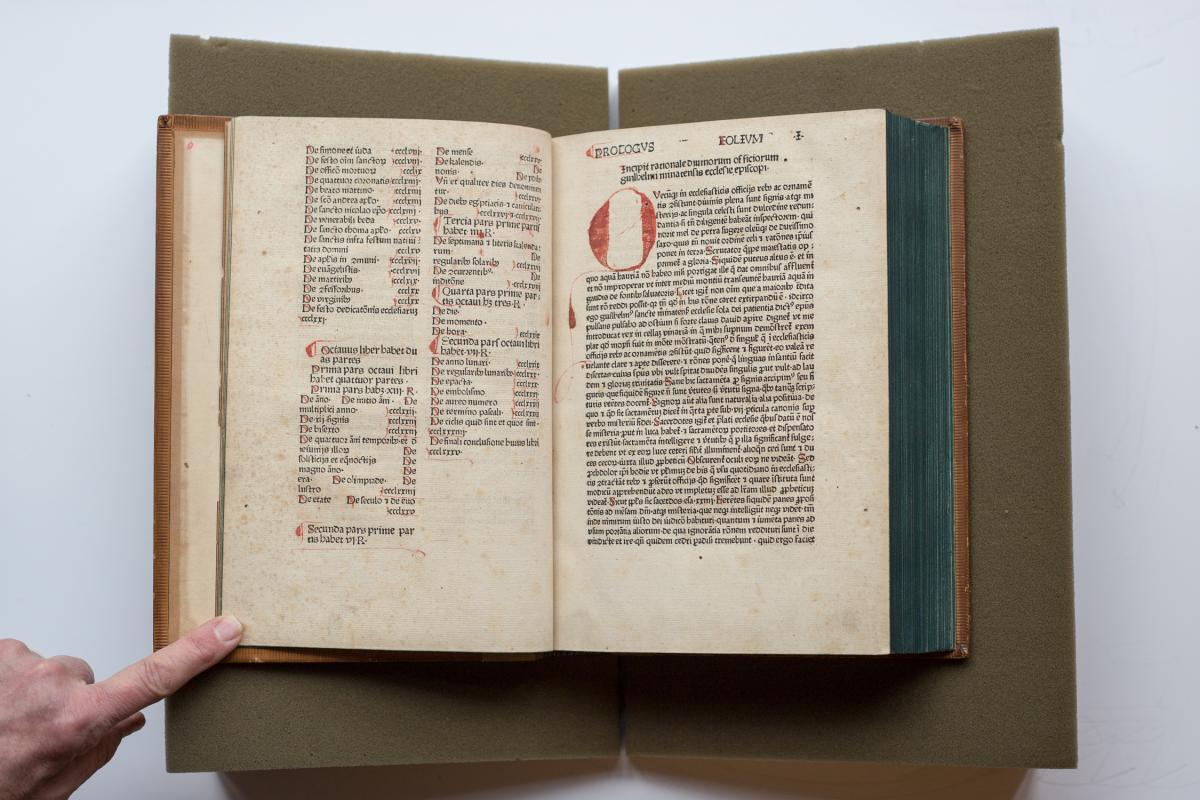

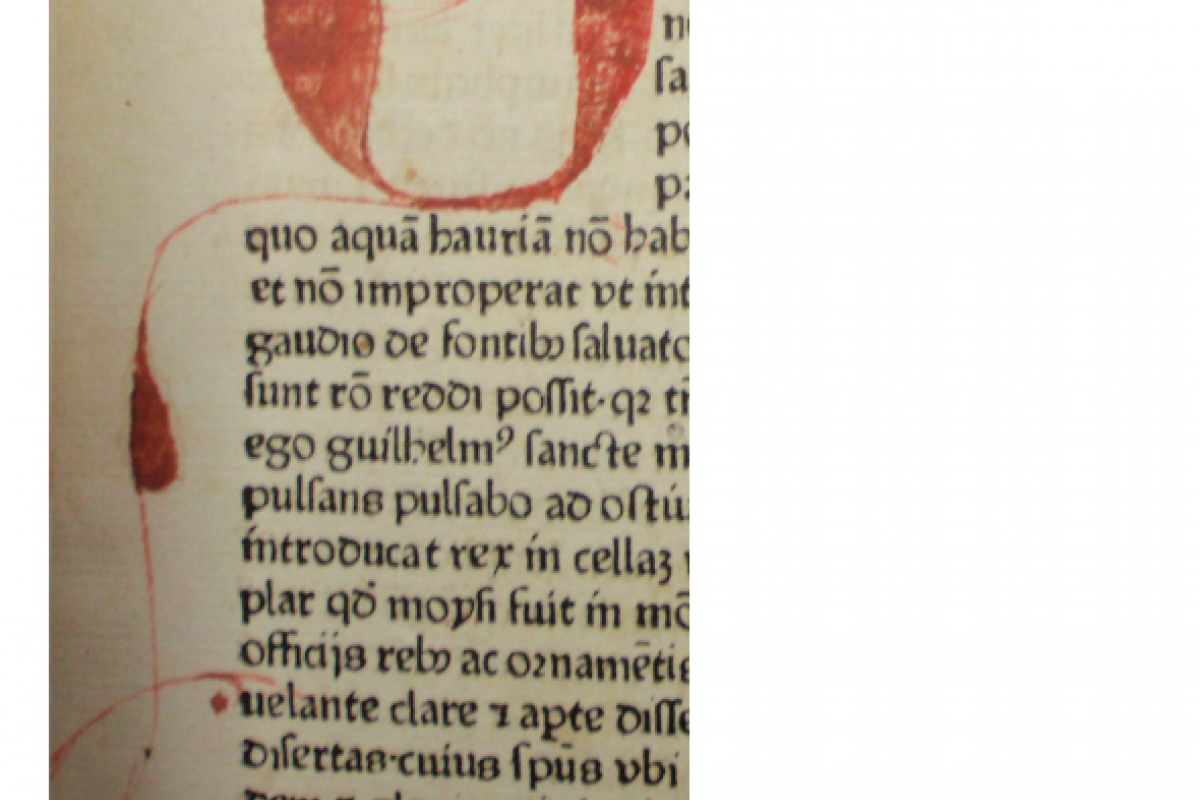

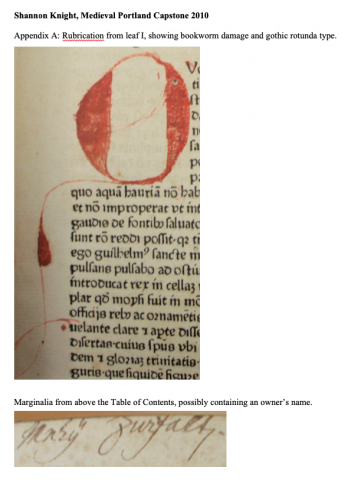

Incunabula were sold with various levels of decoration complete; the remaining work could be commissioned by the book's buyer [28]. The first pages of the Portland Rationale have red, diagonal strokes through capitals, some red underlining, and very poor, red rubrication [29], meaning large, decorative letters. Most of the manuscript is empty of decoration, with blank boxes for rubrication to be completed at a future date. The owner could have begun decorating the manuscript himself, stopping after only a few pages. Buehler notes that "the consequence of amateur enthusiasm, slipshod in the extreme" was particularly prevalent in 15th-century, German books [30].

Evidence of an owner's scholarship is shown in the marginalia, or marginal comments, throughout the incunabulum [31]. The notes are written in Latin by a single hand using a quill pen [32]. These traditional notes include mnemonic devices such as redundant numbers, or repeated numbers listed in the text, keywords from the text, references to note the text, and manicules [33], or pointing hands, highlighting particularly important concepts [34]. Other marginalia includes the highlighting or striking of certain lines with brown ink [35]. A possible owner's name [36] is written at the top of the first page of the table of contents, but the trimming of the paper, likely done at the time of re-binding, along with the tradition of abbreviating handwritten Latin notes [37], makes it difficult to distinguish

Notes:

[1] Also known as William Duranti, Durantis, or Durandus. Fortescue, A, New Advent Catholic Encyclopedia (New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1909), s.v. "William Durandus." http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/05207a.htm.

[2] The Rationale was one of a half-dozen long books prior to 1461, which were in constant, high demand.

Bühler, Curt, The Fifteenth Century Book: The Scribes, the Printers, the Decorators (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1960) 42.

[3] Thibodeau, Timothy, “Enigmata Figurarum: Biblical Exegesis and Liturgical Exposition in Durand’s “Rationale,” The Harvard Theological Review 86, no. 1 (Jan 1993): 65, http://www.jstor.org.

[4] Fortescue, New Advent Encyclopedia.

[5] Mâle, Émile, Religious Art in France, the Thirteenth Century, Edited by Harry Bober, Translated by Marthiel Mathews (Princeton: Princeton UP, 1984), 21.

[6] Gellrich, Jess, The Idea of the Book in the Middle Ages: Language, Theory, Mythology, and Fiction (London: Cornell UP, 1985), 42.

Mâle, Religious Art in France, the Thirteenth Century, 21.

[7] These modes include historical, allegorical, tropological or moral, and anagogical or eschatological.

Durand, Guillaume, The Rationale Divinorum Officiorum of William Durand of Mende, Trans. T. Thibodeau (New York: Columbia UP, 2007), 3.

[8] Fortescue, New Advent Encyclopedia.

[9] The card catalog details a cancel, a replaced section of the text, on leaf LVII, which does not exist. The attributed printer, Georg Husner, and date of printing, ca. 1479, are based on this same match found via Goff’s census of American incunabula, and are thus unreliable, although they coincidentally match other evidence found.

[10] The date of purchase is handwritten in ink upon the advertisement in the bottom corner.

[11] Copy says: “William Ridler, 45, Books EARLY Printing, 1459,--Durand (D.) Rationale Divinorum Officiorum, thick sm. Folio, printed in large gothic letter, THICK VELLUM PAPER, FINE COPY, dark brown calf nt., lettered on back “Moguntiæ, 1459,” A MOST ANCIENT EDITION, £4 10s Absque ulla Nota, c. 1459. A most important work on Liturgical matters of the Middle Ages, The Fountain head of all our Ecclesiastical Rites and Ceremonies. –Brand. A SPLENDID EXAMPLE OF ANCIENT PRINTING, lately priced by Toovey TEN GUINEAS.”

[12] Kidd, Peter, “Catalogue of the Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts c. 1300—c. 1500 from the Collection of T. R. Buchanan in the Bodleian Library, Oxford,” http://www.bodley.ox.ac.uk/dept/scwmss/wmss/online/medieval/buchanan/buchanan.html.

[13] Gaskell, Philip, A New Introduction to Bibliography (New York: Oxford UP, 1972), 152.

[14] The paper is clearly machine-made due to the watermark being on the side opposite the mold lines. Chain lines, or mold lines, confusingly designate the book layout as that of a quarto rather than a folio, but McMullin notes in his study that A. Cowan & Sons followed some non-traditional practices in their paper layout, including placing their watermarks in a pre-1794 position. The manuscript’s older paper’s chain lines run parallel with the binding, revealing the incunabulum to be a true folio, as it appears.

McMullin, B. J., “Watermarks and the Determination of Format in British Paper, 1794—circa 1830,” Studies in Bibliography 56 (2003-2004): 307, 310.

[15] Watermarks on the new paper include a large crown similar to those used in the Lily of Strasburg watermarks, a heart ending in an upturned fleur-de-lis pointing at a cursive “AC&S,” block-lettered “A. Cowan & Sons,” and block-lettered “1848,” with the eights formed by circles with diagonal lines cut through them. Each image is located on a different page.

[16] Bremner, David, The Industries of Scotland: Their Rise, Progress, and Present Condition (Edinburgh: Adam and Charles Black, 1869), http://www.electricscotland.com/history/industrial/industry14.htm.

[17] Dated paper is not always used entirely within the year of the date printed on it.

Hunter, Dard, Papermaking: The History and Technique of an Ancient Craft, 411-12.

[18] The bull’s head watermark, 42mm tall by 32mm wide, is located between the second and third chain lines, which are 40mm wide. The bull has outward-turned horns, ears, eyes, and an open mouth with a line leading from the mouth to the circle below it. It is very similar to Briquet style number 14.901.

Briquet, C. M., Les Filigranes, Vol. 4. P-Z. 2nd ed. (New York: Hacker Art Books, 1966), 748.

[19] The cross watermark, 60 mm tall by 32mm wide with the shaft of the cross being 25mm tall, is located between the second and third chain lines, which are 42mm wide. The cross is of the double-line variety, meaning that it has width; it connects to the triple mount with no dividing line between the mount and the cross; it is of Briquet style number 5645.

Briquet, C. M, Les Filigranes, Vol. 2, Ci-K. 2nd ed. (New York: Hacker Art Books, 1966), 333.

[20] Exact matches of watermarks, with corresponding measurements of the form and placement of the watermark, are used to date and place manuscripts.

[21] The most similar matches were dated from 1478-1480. Wenger identified papers from Geneva, Switzerland; Augsburg, Germany; and Ulm, Germany as having very similar bull’s head watermarks.

Haidinger, Alois, Maria Stieglecker, and Franz Lackner, Wasserzeichen des Mittelalters, Austrian Academy of Sciences (2007), http://www.ksbm.oeaw.ac.at/wz/wzma.php.

• Heawood, Edward, Monumenta Chartæ Papyraceæ Historiam Illustrantia, Vol. 1. Watermarks (Hilversum: Paper Publications Society, 1957), 85.

• Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, Piccard Watermark Collection, http://www.piccard-online.de.

• Watermarks in Incunabula Printed in the Low Countries, Koninklijke Bibliotheek, http://watermark.kb.nl/.

• Wenger, Emanuel, The Memory of Paper, The Bernstein Consortium, Commission for Scientific Visualization, Austrian Academy of Sciences, http://www.memoryofpaper.eu:8080/BernsteinPortal/.

Other watermark collections consulted did not have similar watermarks. These include:

• Castagna, Andrea, and Gregorio Montanari. Le Filigrane degli Archivi Genovesi. Trans. Caterina Pozzi. Cattedra di Bibliografia e Biblioteconomia and Laboratorio di Storia Quantitativa. http://www.labo.net/briquet/.

• Churchill, W. A., Watermarks in Paper in Holland, England, France. Etc. in the XVII and XVII Centuries and Their Interconnection (Gouda: Koch & Knuttel, 1935).

• Mosser, Daniel W., Ernest W. Sullivan II, Len Hatfield, and David H. Radcliffe. The Thomas L. Gravell Watermark Archive: The Unpublished Watermarks and Records of Ch.-M. Briquet Archive

[22] Gaskell, A New Introduction to Bibliography, 18.

[23] Baer, Joseph, Codices Manu Scripti Saeculorum IX. AD XIX. Incunabula Xylographica et Typographica (Frankfurt: Hoch Strasse, 1921), http://books.google.com.

Kemper, Julie Ann, “A Short-Title Catalogue of Incunabula in the Vassar College Library,” http://specialcollections.vassar.edu/Incunabula/stc.htm.

Walsh, James, A Catalogue of the Fifteenth-Century Books in the Harvard University Library. Vol. 1. Books Printed in Germany, German-speaking Switzerland, and Austria-Hungary (Binghamton: Medieval & Renaissance Texts & Studies, 1991), 57.

[24] Putnam, Geo, Books and Their Makers During the Middle Ages. Vol. 1, 476-1600. (New York: Hillary House, 1962), 383.

[25] Chrisman, Miriam Usher, Lay Culture, Learned Culture: Books and Social Change in Strasbourg, 1480-1599 (New Haven: Yale UP, 1982), 4.

[26] Chrisman, Lay Culture, Learned Culture, 35.

[27] Goff lists these printing dates for Husner’s Rationale: not after 1478, c. 1479, not after 1479, not after 1483, 1484, 13 July 1486, 1 Sept. 1488, and 19 July 1493.

Goff, Frederick Richmond, and Margaret Bingham Stillwell, Incunabula in American Libraries; a Third Census of Fifteenth-Century Books Recorded in North American Collections (New York: Bibliographical Society of America, 1964), 223-5.

[28] Lotte, Hellinga, “Peter Schoeffer and the Book-Trade in Mainz,” Book-Bindings & Other Bibliophily, Ed. Dennis Rhodes (Verona: Valdonega, 1994), 161.

[29] Example shown in Appendix A.

[30] Bühler, Curt, The Fifteenth Century Book: The Scribes, the Printers, the Decorators (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1960), 75.

[31] Scholarly medieval readers were taught to write in the margins of their books.

Sherman, William, Used Books: Marking Readers in Renaissance England (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008), 3.

[32] The use of a quill pen is especially evident through rare ink splatters caused by the pen needing trimmed, particularly on leaf CCCXVIII.

Nickell, Joe, Pen, Ink, & Evidence: A Study of Writing and Writing Materials for the Penman, Collector, and Document Detective (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1990), 7.

[33] Manicule samples shown in Appendix B.

[34] Heinlen, Michael, and Paul Saenger, “Incunable Description and Its Implication for the Analysis of Fifteenth-Century Reading Habits,” Printing the Written Word: The Social History of Books, circa 1450-1520, Ed. Sandra Hindman (Ithaca: Cornell UP, 1991), 249.

[34] Sherman’s Used Books expands upon reader markings, including the striking of text.5

[36] Shown in Appendix A.

[37] The final “y” letter could be an abbreviation for any “s” ending, for instance changing “Mary” to “Marius.” The superscript after the first word could be an abbreviation for end letters of the previous word or the descender of a line of higher text that was cut off when the paper was trimmed.

Cappelli, Adriano, The Elements of Abbreviation in Medieval Latin Paleography. Trans. David Heimann and Richard Kay (Lawrence: University of Kansas Libraries, 1982), i.

Minert, Roger, Deciphering Handwriting in German Documents: Analyzing German, Latin, and French in Vital Records Written in Germany (Otterbach: GRT Publications, 2001), 80-83.

Bibliography

Baer, Joseph. Codices Manu Scripti Saeculorum IX. AD XIX. Incunabula Xylographica et Typographica. Frankfurt: Hoch Strasse, 1921. http://books.google.com.

Bremner, David. The Industries of Scotland: Their Rise, Progress, and Present Condition. Edinburgh: Adam and Charles Black, 1869. http://www.electricscotland.com/history/industrial/industry14.htm.

Bringhurst, Robert, and Warren Chappell. A Short History of the Printed Word. 2nd ed. Point Roberts: Hartley & Marks, 1999.

Briquet, C. M. Les Filigranes. Vol. 2. Ci-K. 2nd ed. New York: Hacker Art Books, 1966.

---. Les Filigranes. Vol. 4. P-Z. 2nd ed. New York: Hacker Art Books, 1966.

Bühler, Curt. The Fifteenth Century Book: The Scribes, the Printers, the Decorators. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1960.

Cappelli, Adriano. The Elements of Abbreviation in Medieval Latin Paleography. Trans. David Heimann and Richard Kay. Lawrence: University of Kansas Libraries, 1982.

Castagna, Andrea, and Gregorio Montanari. Le Filigrane degli Archivi Genovesi. Trans. Caterina Pozzi. Cattedra di Bibliografia e Biblioteconomia and Laboratorio di Storia Quantitativa. http://www.labo.net/briquet/.

Chrisman, Miriam Usher. Bibliography of Strasbourg Imprints, 1480-1599. London: Yale UP, 1982.

---. Lay Culture, Learned Culture: Books and Social Change in Strasbourg, 1480-1599. New Haven: Yale UP, 1982.

Churchill, W. A. Watermarks in Paper in Holland, England, France. Etc. in the XVII and XVII Centuries and Their Interconnection. Gouda: Koch & Knuttel, 1935.

Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft. Piccard Watermark Collection. http://www.piccard-online.de.

Durand, Guillaume. The Rationale Divinorum Officiorum of William Durand of Mende. Trans. T. Thibodeau. New York: Columbia UP, 2007.

Fortescue, A. New Advent Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1909. http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/05207a.htm.

Gaskell, Philip. A New Introduction to Bibliography. New York: Oxford UP, 1972.

Gellrich, Jess. The Idea of the Book in the Middle Ages: Language, Theory, Mythology, and Fiction. London: Cornell UP, 1985.

Goff, Frederick Richmond, and Margaret Bingham Stillwell. Incunabula in American Libraries; a Third Census of Fifteenth-Century Books Recorded in North American Collections. New York: Bibliographical Society of America, 1964.

Haidinger, Alois, Maria Stieglecker, and Franz Lackner, Wasserzeichen des Mittelalters, Austrian Academy of Sciences (2007), http://www.ksbm.oeaw.ac.at/wz/wzma.php.

Heawood, Edward. Monumenta Chartæ Papyraceæ Historiam Illustrantia, Vol. 1. Watermarks. Hilversum: Paper Publications Society, 1957.

Heinlen, Michael, and Paul Saenger. “Incunable Description and Its Implication for the Analysis of Fifteenth-Century Reading Habits.” Printing the Written Word: The Social History of Books, circa 1450-1520. Ed. Sandra Hindman. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 1991. 225-58.

Hunter, Dard. Papermaking: The History and Technique of an Ancient Craft. New York: Dover, 1978.

Kemper, Julie Ann. “A Short-Title Catalogue of Incunabula in the Vassar College Library.” http://specialcollections.vassar.edu/Incunabula/stc.htm.

Kidd, Peter. “Catalogue of the Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts c. 1300—c. 1500 from the Collection of T. R. Buchanan in the Bodleian Library, Oxford.” http://www.bodley.ox.ac.uk/dept/scwmss/wmss/online/medieval/buchanan/buchanan.html.

Lotte, Hellinga. “Peter Schoeffer and the Book-Trade in Mainz.” Book-Bindings & Other Bibliophily. Ed. Dennis Rhodes. Verona: Valdonega, 1994.

Mâle, Émile. Religious Art in France, the Thirteenth Century. Edited by Harry Bober. Translated by Marthiel Mathews. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1984.

McMullin, B. J. “Watermarks and the Determination of Format in British Paper, 1794—circa 1830.” Studies in Bibliography 56 (2003-2004): 295-315.

Minert, Roger. Deciphering Handwriting in German Documents: Analyzing German, Latin, and French in Vital Records Written in Germany. Otterbach: GRT Publications, 2001.

Mosser, Daniel W., Ernest W. Sullivan II, Len Hatfield, and David H. Radcliffe. The Thomas L. Gravell Watermark Archive: The Unpublished Watermarks and Records of Ch.-M. Briquet Archive (Ms Briquet XXX) at the Bibliotèque de Genève. The University of Delaware. http://www.gravell.org.

Nickell, Joe. Pen, Ink, & Evidence: A Study of Writing and Writing Materials for the Penman, Collector, and Document Detective. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1990.

Overty, Joanne Filippone. “The Cost of Doing Scribal Business: Prices of Manuscript Books in England, 1300-1483.” Book History, no. 11 (2008), http://muse.jhu.edu.

Putnam, Geo. Books and Their Makers During the Middle Ages. Vol. 1. 476-1600. New York: Hillary House, 1962.

Sherman, William. Used Books: Marking Readers in Renaissance England. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008.

Thibodeau, Timothy. “Enigmata Figurarum: Biblical Exegesis and Liturgical Exposition in Durand’s “Rationale.” The Harvard Theological Review 86, no. 1 (Jan 1993): 65-79, http://www.jstor.org.

Walsh, James. A Catalogue of the Fifteenth-Century Books in the Harvard University Library. Vol. 1. Books Printed in Germany, German-speaking Switzerland, and Austria-Hungary. Binghamton: Medieval & Renaissance Texts & Studies, 1991.

Wenger, Emanuel. The Memory of Paper. The Bernstein Consortium, Commission for Scientific Visualization, Austrian Academy of Sciences. http://www.memoryofpaper.eu:8080/BernsteinPortal/.

Watermarks in Incunabula Printed in the Low Countries, Koninklijke Bibliotheek, http://watermark.kb.nl/.