Secular Text from Juvenal Satira XIII

Secular Text from Juvenal Satira 13, lines 1-44

Italian, ca. 1400

Language: Latin

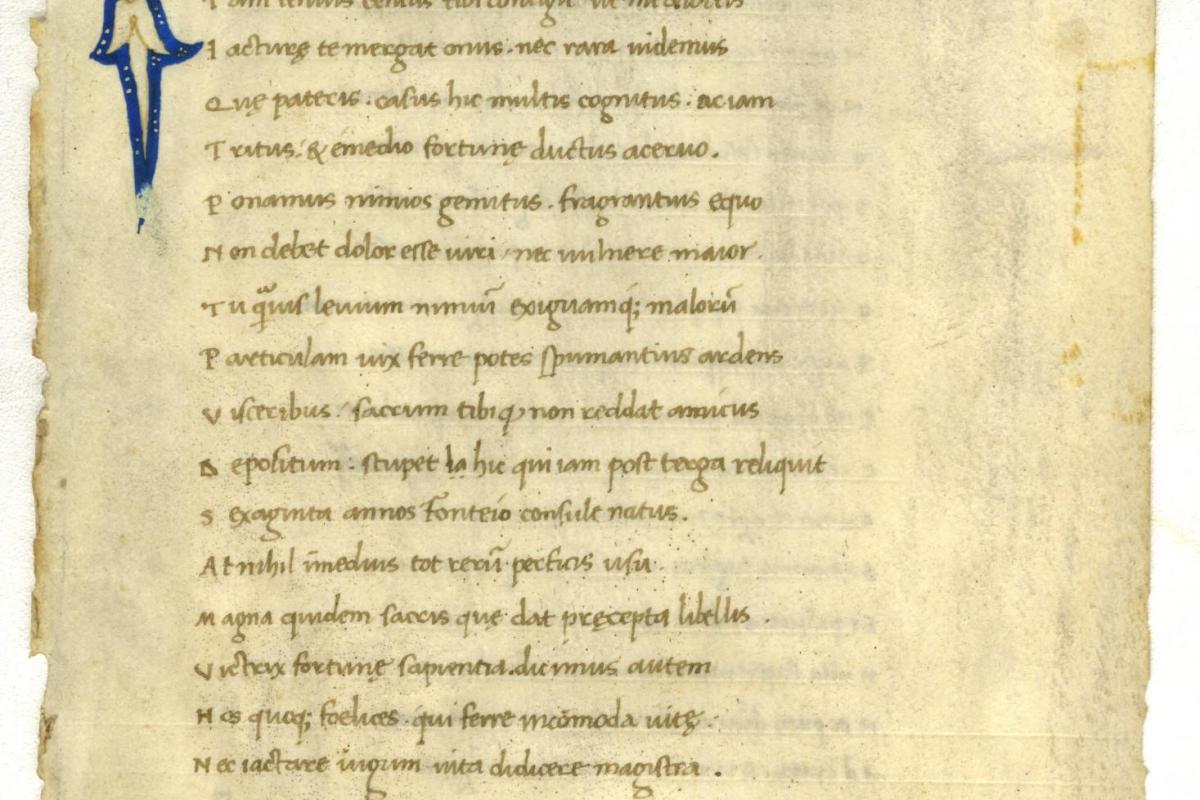

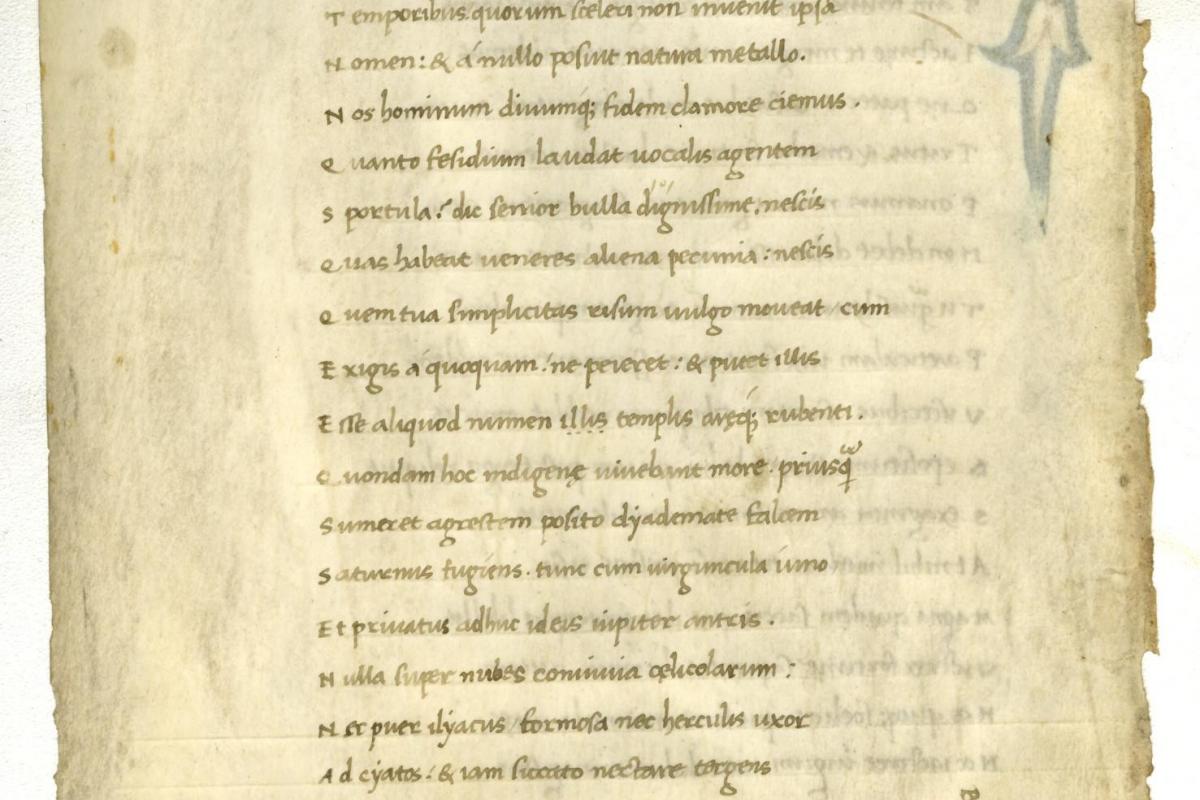

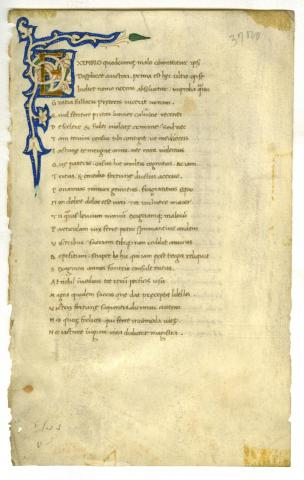

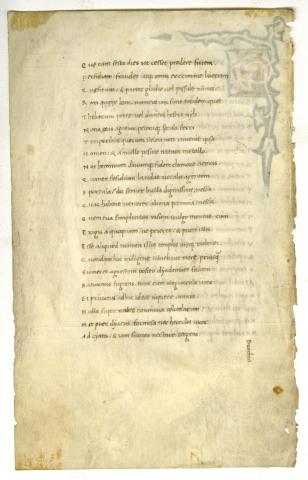

Single leaf. Beginning initial "E" decorated with a leaf and scroll design in blue, green, and pink paints, and illuminated with gold leaf. Lines scored and capitals set off along the left margin to start each line.

ink on vellum

height 18.5 cm

width 11.5 cm

Reed College Library Special Collections, Lloyd Reynolds 3

Gift of Lloyd Reynolds

Evan Clary, Medieval Portland Capstone student, 2016

This single leaf of Roman satirist Juvenal’s Satire XIII[1] is believed to have been produced in 15th-century Italy. The page is written in "fine Italian scribal hand," with the initial E of the work illuminated in gold leaf and decorated with an assortment of blue, green, and pink paints.[2] The contents of this first page can be seen on the reverse, where the writing continues. Upon examination and research, the entire leaf appears to contain the beginning of Juvenal’s Satire XIII to line 44, giving a glimpse into the role Juvenal played in the time that this leaf was written.

Juvenal had been an influential Roman satirist, known for penning harsh critiques of Roman society between 100 and 127 CE, aimed at multiple social strata.[3] Roman satire had acted as a unique literary form marked by, "variety, comic situations, and low diction" that was made unique by elements of, "personal abuse and social criticism." [4] In this way, Roman satires allowed for social opinions to be expressed artfully, but not always tastefully, as is the case with the modern iterations of comedic satire. Juvenal, in particular, only has a surviving work consisting of five books, containing a total of sixteen satires. "Satire XIII" is found in Book V, beginning in Latin as “Exemplo quodcumque malo committitur, ipsi/ displicet auctori"[5], translated as "Setting a bad example won’t make the perpetrator feel pleased."[6] The satire goes on to dissuade anger or revenge for being the victim of a fraud, either emotional or monetary, and to pursue more moderate responses, though the leaf itself only contains the first 44 lines of the 249-line work.

Juvenal, as a writer of satires, was known for these and similar takes on morality and responses to the times in which he lived. These views may have allowed for his being "one of the classical authors most widely read throughout the Middle Ages" as he was admired for his "uninhibited…attacks on vice" and "against avarice, luxury and lust, and against women."[7] More specifically, Juvenal was often used in schooling at the time, teaching both the lessons instilled by the satires themselves but also as a tool to discuss the controversies presented. Thus, Juvenal’s legacy in the Medieval Age can be said to not be completely positive, though widely popular. Accordingly, he had been described by Pope Pious II as "a poet of great genius" and by Pope Paul II, Pious II's successor, as "a teacher of vice."[8] These commentaries by Pope Pious II and Pope Paul II, both living in the mid-15th Century, give credence to the fact that Juvenal’s legacy and works existed at this time, the time when this particular leaf is believed to have been produced. Juvenal’s usage in schools and other academia then gives weight to the idea that the manuscript this leaf comes from may have been academic in origin, either used directly to teach Juvenal or used in the study of his works.

The artifact itself, though, shows signs of wear in both its historical journey and the preparation to sell the leaf. The left side of the leaf that presumably was attached to the original work's spine appears to show the tearing out of that work, or later damage that would have caused the leaf to leave the original manuscript. The left side should be contrasted against the relatively well-preserved right side of the leaf. However, the page shows stains of unknown origin perhaps from its storage or from more contemporary handling. Finally, the face of the leaf with the illuminated E has two pencil marks on the top-right and bottom-left corners, the former possibly showing the sale price and the latter unintelligible. Other than this, no other notes, either contemporary or historical, appear on the document aside from the original script.

Though it is unknown for what purpose the larger manuscript was produced, or even how expansive the original manuscript was, this single leaf has allowed for a glimpse into the legacy of an influential, and controversial, figure in literature. The fact alone that Juvenal, as a writer and satirist, has survived to today gives credence to his ultimate impact on literary history the world over.

NOTES

[1] "D. Iunis Iuvenalis Satura XIII." The Latin Library. Accessed April 20th, 2016. http://www.thelatinlibrary.com/juvenal/13.shtml.

[2] "Secular Text from Justinian." Early Printing & Writing Collection. Accessed March 30th, 2016. http://cdm.reed.edu/cdm4/document.php?CISOROOT=/eptg&CISOPTR=1026&REC=1.

[3] Braund, Susanna Morton., and Josiah Osgood. A Companion to Persius and Juvenal. Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley Blackwell, 2012.

[4] Freudenburg, Kirk. The Cambridge Companion to Roman Satire. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

[5] (endnote missing in the original document)

[6] Decimus Juni Juvenal. Satura XIII. Translated by A.S. Kline. Rome: n.a. c. 127. Retrieved from http://web.ics.purdue.edu/~rauhn/Hist_416/hist420/JuvenalSatirespdf.pdf.

[7] Sanford, Eva Matthews. "Renaissance Commentaries on Juvenal." Sweet Briar College VIII (1948): 92.

[8] Braund, Susanna Morton, and Josiah Osgood. A Companion to Persius and Juvenal. Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley Blackwell, 2012. Contained in Section 19.5 "The Imperial Satirists in Renaissance Classrooms". Pope Pius II's quote is from his De Liberorum Educatione (1450), and Pope Paul II's is reported by Blanchus, ambassador of Milan, in 1468.